summary学术英语literature review

Content-based the risk of nuclear power and the

damage of its radioactivity

An earthquake struck Japan in 2011 which severely damaged nuclear reactor at the Fukushima plant, sparking the release of radioactive materials. People are worried about its awful effects to us.So we should learn more about the nuclear power and the damage of its radioactivity.The risk of nuclear power is main from its radiation, reactor accidents, radioactive waste and other radiation problems.At the same time, the risk that estimated by PRA from reactor accidents is very low (Bernard L.Cohen). Next, it is necessary to know that radiation is spread in the form of waves or particles and the health effects caused by radiation exposure depend on its level, type and duration (Nina Bai,2010 & Susan Blumenthal).But on the one hand, some others think that there is no doubt that the radiation is a potential threat to our health and the radiation exposing to the milk and food of the U.S after Fukushima disaster is the powerful evidence (Amber Cornelio). On the other hand, some scholar has the opinion that the advantages are more much than the disadvantages the nuclear power has (Bernard L.Cohen). In conclusion, the unclear power has his advantage but the radioactivity releasing from it has damage to the health of people more or less.(207words)

第二篇:Economic Regulation A Preliminary Literature Review and Summary

Centre on Regulation and Competition

ISBN:

Further details:

Published by: WORKING PAPER SERIES Paper No. 6 ECONOMIC REGULATION: A PRELIMINARY LITERATURE REVIEW AND SUMMARY OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS ARISING David Parker University of Aston October 2001 1-904056-05-9 Fiona Wilson, Centre Secretary

Centre on Regulation and Competition,

Institute for Development Policy and Management, University of Manchester, Crawford House, Precinct Centre, Oxford Road, MANCHESTER M13 9GH Tel: +44-161 275 2798 Fax: +44-161 275 0808 Email: crc@man.ac.uk Web: http://idpm.man.ac.uk/crc/

ECONOMIC REGULATION: A PRELIMINARY LITERATURE REVIEW AND SUMMARY OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS ARISING

1. INTRODUCTION

In recent years market liberalisation and privatisation have been championed as a means of spreading the benefits of globalisation world-wide (ed. Ramanadham, 1993). Policies favouring market liberalisation and privatisation have been advanced by economists (e.g. Aharoni, 1986; Hanke, 1987; eds. Cook and Kirkpatrick, 1988; Vickers and Yarrow, 1988; Shapiro and Willig, 1990; Boycko, Shleifer and Vishny, 1996; Lal, 1997) and the main international aid and trade bodies, particularly the World Bank, IMF, OECD, Asian

Development Bank and latterly the new World Trade Organisation (WTO) (Ikenberry, 1990, p.100; Ramamurti, 1992; World Bank, 1995). In response more than 100 countries now claim to have privatisation programmes. Last year global privatisation receipts rose to a record US$200bn. (Privatisation International, January 2001). At the same time, however, the World Bank has noted that the share of employment of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in developing economies may be the same now as in the early 1980s (cited in Rondinelli, 1997, p.3). In a number of countries privatisation seems to have been more talked about than carried out (e.g. Cooke and Minogue, 1990; Adam, Cavendish and Mistry, 1992, p.39; eds. Cook and Kirkpatrick, 1995; Astbury, 1996; Fundanga and Mwaba, 1997; Parker, 1998a, 1999a).

This paper is concerned with providing a preliminary literature review based largely on the economics of regulation literature. Much of this is based on the institutions and experiences of developed economies and notably the US and UK. A later paper will review the literature on regulation relating specifically to developing economies. From this preliminary literature review a series of research questions is generated. These research questions form the basis for my research on regulation within the Centre on Regulation and Competition in the

Institute for Development Policy and Management at the University of Manchester over the next four and a half years, although the forthcoming review of developing country literature may lead to some additions and changes to these questions.

The research complements recent policy initiatives of Department for International

Development (DFID). The mission of DFID’s Enterprise Development Department, as set 2

out in the document DFID Enterprise Development Strategy published in June 2000, is ‘to promote enterprise as a means to eliminate poverty’ and thereby contribute to the

international development target of halving the proportion of people in developing countries living in extreme poverty by 2015. This strategy emphasises ‘the fundamental importance of the private sector as the driving force to attain these goals’ (DFID, 2000, para.1.2). Fostering private enterprise requires a favourable environment for entrepreneurship and investment, whether in large, small or micro businesses. This in turn requires reducing impediments to legitimate private enterprise, including badly formulated and poorly implemented

government laws and regulations. Many developing countries suffer from a legacy of heavy state intervention, leading to distorted markets and resource misallocation. The DFID strategy document singles out three areas of particular concern:

1. The need to improve the legal and regulatory enabling environment for enterprise (at all levels).

2. Developing financial markets, institutions and instruments to support enterprise growth (particularly for micro, small and medium-scale enterprise).

3. Addressing constraints in management, technologies and market knowledge (for small and medium-scale enterprise).

The research agenda proposed later in this paper addresses the first of these concerns by improving understanding of the current regulatory environment in developing countries, the methods by which this regulatory environment can be improved, and by regulatory capacity building in developing countries (through education, training, institutional reform etc.). The research also addresses the third concern by assessing the inter-relationship between the regulatory environment in developing countries and management capability, technological change and market development. The research will embrace issues to do with market knowledge, communication (including networking) and institutional linkages. Finally, the research will contribute to understanding of how regulation impacts on financial markets and enterprise growth. Although the research will not be directly concerned with the regulation of financial markets (this is the subject of a separately funded research programme under Professor Colin Kirkpatrick at the Institute for Development Policy and Management, University of Manchester), the extent to which wider economic regulation constrains the development of financial markets and investment will be considered (e.g. the impact on 3

domestic capital markets of privatisation and market liberalisation; the impact of regulation on the cost of capital).

Another area of the research consistent with the mission of DFID’s Enterprise Development Department will be concerned with understanding the effects of regulation and market liberalisation on social values and conditions, including issues to do with pay and working conditions, employment, health and safety, gender discrimination, quality and safety,

household economic security, income diversification, fair trading and ethical investment. The research may also consider environmental issues including the interrelationship between regulation, market liberalisation and the safeguarding of rural and urban environments. Taxation is a field of specialised regulation and because of its scale and complexity it is not intended to look at taxation in detail, although it cannot be ignored entirely.

The research will cover both policy formulation and implementation because policy can be distorted by poor implementation, including the effects of poor communication and inadequate enforcement, to cronyism and outright corruption. The DFID Enterprise

Development Strategy (2000) refers to ‘reasonable regulation’ (para.3.2.1) and ‘competent legal and regulatory institutions’ (para.3.6.2). The research will foster understanding of what is reasonable regulation and what are competent regulatory institutions within the specific context of developing economies. It will also highlight the role and limitations of regulation and deregulation in poverty reduction and the nature of the necessary supporting economic and social policies and political choices that have to be made (this is consistent with the thrust of the reports of other development agencies e.g. World Bank, 1995; Asian Development Bank, Financial Times, 5 January 2001, p.11). Throughout, poverty will be defined in terms both of material deprivation and a lack of opportunity for individuals to contribute fully to their community.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Part 2 is concerned with important issues or themes in the economics of regulation that establish the basis for the research agenda. Part 3 details the proposed research questions that arise from the literature and Part 4 provides conclusions.

4

2. ISSUES IN THE ECONOMICS OF REGULATION

Economic regulation affects economies at different levels. Research needs to address its nature and consequences at national, local (state, municipal etc) and international levels. Also, although it has been common in developed countries such as the USA and UK to focus on regulation and large firms, for example the regulation of large telecommunications businesses, in the context of developing countries it is also particularly necessary to consider how regulation affects small and medium-sized firms (SMEs) and micro-enterprises because of their importance to the economy. Moreover, regulation can take different forms, for example of utilities, health and safety, labour laws, environment, etc. Alongside particular regulatory issues for each sector some common considerations apply, which are the focus of this paper. Figure 1 provides a schema for assessing different types of regulatory structure.

Source: Parker (1999d)

5

Regulation impacts on enterprises both directly and indirectly and a proper analysis the effects requires a detailed ‘regulatory impact assessment’.

? Direct effects relate to the impact on property rights and therefore self-employment and small-scale entrepreneurship.

? Indirect effects include how regulations affect the economy through wider impacts; for example, small firms may be affected by regulations on larger firms that consequently alter their procurement policies, impacting adversely (or perhaps in some cases

beneficially) on smaller businesses. To date there has been very little research into the effects of market liberalisation, including privatisation, on supply or value chains (vertical linkages) even in the developed economies.regulation and deregulation on the development of essential infrastructures, such as power, clean water, roads, ports, telecommunications and so on.

In this part of the paper a number of key issues in the economics of regulation are reviewed. These issues are important in understanding both the nature and impact of regulation. These issues are: (i) the economics of market failure; (ii) the economics of state failure; (iii) the economics of regulating prices and profits; (iv) regulatory efficiency, legitimacy and risk; (v) the impact of regulation on business; and (vi) the nature of policy transfer.

2.1 The Economics of Market Failure

When competition exists, resource allocation through unimpeded markets is expected to produce higher economic welfare than resource allocation through state planning.

Competitive markets can lead to a Pareto optimal solution where no further redistribution of resources will raise economic welfare. There are, however, well-recognised circumstances in which markets may ‘fail’ to do so. In particular, market failure occurs where there are:

? Significant externalities: so that all gains and costs are not captured by the direct

participants in the economic exchange. For example a production process may lead to appreciable pollution (an ‘external cost’) that impacts adversely on society; while an 1 For example, for the UK the only major study is that by Cox, Harris and Parker ,1999; also, Harris, Parker and Cox, 1998.

6

inoculation campaign against a major disease may benefit not just those who pay to be inoculated but others too by stemming the spread of disease (an ‘external benefit’). ? Public goods: these are goods and services where non-payers cannot be excluded from the benefits of the provision of a good or service; at the same time supplying one person with the good or service does not prevent supply to someone else. This means that the economic (opportunity) costs of extending supply to additional consumers is zero or negligible, so that there is no economic case for restricting the supply. In other words, public goods are associated with the two conditions of non-excludability and non-rivalry. Where a good or service is non-excludable, there will be a tendency for consumers to ‘free ride’, refusing to pay for its provision but nonetheless benefiting from its

consumption.

? Merit and demerit goods: there may be some types of goods and services where society considers supply should not be restricted to those willing or able to purchase. Oft-cited examples of merit goods are education, housing and health care. Equally, there may be demerit goods, such as certain drugs, tobacco and alcohol, where the state considers that supply should be prohibited or reduced by regulation and taxation. The importance of merit goods is controversial, however. The argument leads to allegations of a ‘nanny state’ because the state overrides the normal market signals and augments the supply through direct provision, regulation of private markets (e.g. price limits) or by providing subsidies.

? Incomplete information: markets will tend to allocate resources inefficiently where there are important information imperfections. For example, people may underestimate the risks of ill-health or having inadequate income in old age and therefore under-provide through private insurance. Markets work best where consumers and producers are well informed (ideally, perfectly or completely informed). Where information is incomplete, adverse selection and moral hazard can lead to ‘bads’ driving out ‘goods’ in market ? Incomplete markets: the market may have frictions so that price signals do not produce a socially optimal allocation of resources; for instance where there is factor immobility Adverse selection occurs where one party ex ante to the contract exploits an information asymmetry to negotiate an especially favourable contract (e.g. selling to an unsuspecting party a defective second-hand car). Moral hazard arises where, ex post to the contract, one of the parties has an incentive to exploit the terms of the contract to the disadvantage of the other party (e.g. reducing care when driving because motor insurance has been obtained). Both adverse selection and moral hazard occur due to asymmetric information in market

contracting. Both involve what Williamson (1985) calls ‘opportunism’ or ‘self seeking with guile’ in markets.

72

(geographical and occupational), or where the market will lead to a socially optimal

outcome, but too slowly. Another example of this form of market failure is where markets are ‘missing’ or under-developed (although in the absence of regulatory barriers the profit motive should lead to the necessary markets developing, in time).

? Monopoly: markets may not be competitive. Competition or anti-trust laws and economic regulation of natural monopolies exist to protect consumers from monopoly prices, poor quality services and cartel behaviour. This can be summarised, as it is in EU competition law, in terms of preventing firms from ‘abusing a dominant position’ in markets and preventing ‘restrictive and concerted practices’ between firms that reduce competition. Economic regulation is particularly appropriate where firms have a natural monopoly. production so that competition raises supply costs. This is most likely where there are important sunk costs in the form of networks, pipelines and similar high fixed-cost infrastructure. Examples of industries with important network effects, and therefore

where competition is restricted by the technology and economics of the industry, include electricity and gas transmission and distribution, rail infrastructure, fixed line

telecommunications (though less so today because new technology is reducing network costs) and water and sewerage services.

? Inequality: society may decide that free market outcomes are unacceptable because of the resulting distribution of income and wealth. Redistribution has been an important reason for state intervention in both developing and developed economies. Redistribution involves interference with private property rights (wealth redistribution) or interfering with the outcomes in terms of revenues received from these property rights (income redistribution).

2.2 The Economics of State Failure

The above market failure arguments underpin the economic rationale for state regulation of market economies. For example, health and safety legislation and environmental regulation can be rationalised on imperfect information and externalities grounds. Economic regulation of public utilities can be explained by economies of scale and scope and a resulting need to protect consumers from monopoly exploitation. Aspects of fiscal policy can be rationalised in terms of wealth and income redistribution. At the same time, however, the experience of state 3 Technically, the cost function is ‘sub-additive’.

8

intervention suggests that alongside ‘market failure’ there is ‘state failure’. The case for state intervention can be easily sustained when an ideal, economic welfare maximising government is compared to actual, imperfect markets. But in practice government

intervention may be much less than ‘ideal’. When the economist Alfred Marshall was once asked whether government intervention would be required to solve a particular problem, he is said to have answered: ‘Do you mean government, all wise, all just, all powerful, or government as it now is?’ (cited in Blundell and Robinson, 2000, p.4). At the same time, however, as Ricketts comments (2000, p.ix)): ‘If the old view of government action as entirely benign seems now to be hopelessly flawed, any contrary assumption that private action is always preferable to state regulation would seem to be equally Panglossian.' What is required is comparative institutional analysis, in which neither markets nor state regulations necessarily result in ‘first best’ or ‘socially optimal’ outcomes (Arrow, 1974, pp.11-14).

The case for market liberalisation and privatisation is based on both the poor record of much government intervention in market economies over the years and developments in economics, drawing especially from ‘Austrian’, property rights and public choice theories. Common to these theories, economic regulation is analysed within the framework of actions and processes and information and incentives.

? is centrally concerned with market processes and dynamic

efficiency (Shand, 1984; Kirzner, 1997). In Austrian economics market signals provide information and incentives to ensure that economies continue to change and adapt.

Without market signals the ‘discovery’ process in market economies suffers (Littlechild, 1986; Kirzner, 1985, 1997). The market failure literature centres on deviations from long-run perfectly competitive outcomes. From an ‘Austrian’ perspective, however, supposed market failure may simply be the result of the working out of normal market processes and is associated with temporary economic rents; while state regulation leads to longer-term rents to special interest groups and, eventually, economic sclerosis.

? Property rights and principal-agent theory looks at the importance of residual property right in establishing optimal incentives for principals to contract with and monitor the 4 Other relevant theory includes evolutionary economics and games theory. For reasons of space they are not reviewed here. Also, they have had less influence on attitudes to state intervention. 5 The term ‘Austrian’ denotes an intellectual tradition and not a geographical location.

9

activities of economic agents. In the private sector, where entrepreneurs directly own and control their businesses, they have obvious incentives to reduce economic waste,

including labour slacking, so as to maximise the residual net income or profit. In larger firms, ownership and control tend to be divorced with capital and ultimate residual ownership risks lying with investors and with the control of assets delegated to agents (boards of directors and senior managers). In which case, a principal-agent cost may arise because the principals may lack sufficient information to ensure that their assets are being efficiently managed and agents may lack incentives to prevent waste. In the relevant literature, however, a competitive capital market provides the institutional mechanism to ensure that agents are incentivised to minimise waste under private ownership. Where profit performance is poor and shareholder value dissipated, investors will move their funds to more profitable enterprises. By the trading of shares in stock markets,

information about agents’ demands is created and incentives result for principals to pursue the utility of the agents. In the extreme case, a loss of investor confidence may lead to a share price collapse and a hostile takeover bid. Also, in the private sector agents may incentivise managers by questioning their actions at company annual and extra-ordinary general meetings, by voting to dismiss directors, and through the use of stock options and other profit related managerial remuneration.

By contrast, in this literature the state sector is associated with managerial salaries that are not related to economic performance and an uncompetitive capital market – state

enterprises tend to be funded directly by government or through government loan guarantees. Also, the public are the ultimate principals and bearers of the residual risk (state enterprise losses are financed from taxation) but usually have little if any direct input into decision making processes. Control rights lie in government departments and shares in state enterprises (even when they exist) may not be publicly traded. At the same time, elections are a very imperfect mechanism for aggregating individuals’ views on particular state investments (Arrow, 1970; Mitchell, 1988, pp.36-37). In consequence, state officials lack adequate information about the public’s preferences.6 As Shapiro and Willig (1990, p.65) note in their study of privatisation: ‘The key distinction between public and private-sector enterprise ……is that privatization gives informational autonomy to a party who is not under direct public control.’ In principle, where the state owns an industry it should have good information on costs and revenues and regulate effectively. This should in turn reduce the transaction costs implicit in regulation. These can be expected to be lower that where an arm’s length regulator has to search for information. However, state ownership and direct regulation by government department has been associated with poor incentives to use the information gathered to operate efficiently, meet consumer demands and cut costs.

10

? Public choice theoryrights and principal-agent theory (e.g. Downs, 1957; Buchanan, 1960, 1978; Niskanen, 1971; Tullock, 1976; Mitchell, 1988; Tullock, Seldon and Brady, 2000). While in the principal-agent literature politicians and state officials lack the necessary information to manage state investments in a way consistent with the public interest, public choice theory argues that they also lack the incentive to do so.

Public choice theory rejects the notion of altruistic and disinterested government and argues instead that state employees are generally no different to individuals elsewhere in the economy. Their primary motivation is their own interest or utility. This is associated with, in the words of one of the leading proponents of public choice theory, William Niskanen, “salary, perquisites of the office, public regulation, power, patronage, output of the bureau, ease of making changes, and ease in managing the bureau”(Niskanen, 1971, p.38). The result is an over-supply of public sector outputs - to double the welfare maximising level according to Niskanen’s (disputed) calculation (Cullis and Jones, 1987; Dunleavy, 1991; Udehn, 1996). Moreover, the public choice literature points to lobbying by special interest groups that distorts state outputs in favour of well-organised and politically powerful groups in society (known as rent seeking behaviourbenefit grounds, individual taxpayers may feel that it is not worthwhile actively

challenging the introduction of new regulations; whereas those likely to gain most from the new regulations have every incentive on cost-benefit grounds to lobby hard.Moreover, once the regulatory system is introduced the regulators may themselves become active rent seekers, opposing any steps to reduce their powers and perks.Public choice theory leads to the conclusion that regulation is expanded beyond the economically efficient level: ‘there is a remorseless tendency for government regulation 7

8 Also known as ‘the economics of politics’ or ‘Virginia School’. Rent seeking behaviour refers to individuals attempting to maximise their economic rents. 9 A very good example of this involves honey manufacturers in the USA, who lobbied successfully for a small regulatory change. This brought them an average gain of US$400,000 each per annum, starting in 1987 (in today’s dollars around US$613,000 each per annum). The cost to the average US taxpayer is around 2 cents each year. Unsurprisingly, there has been no widespread lobbying by taxpayers against the measure. The 2 cents gain a year that each taxpayer would benefit from if the regulation were repealed does not even cover the costs of writing to their congressman. I thank John Blundell of the Institute of Economic Affairs, London, for drawing my attention to this example. 10 ‘The self-interest of regulators will, in general, make them tend to exaggerate benefits, under-estimate costs and over-estimate the demand for action on their part’ (Blundell and Robinson, 2000, p.11).

11

to be pushed to levels at which marginal social benefits are well below marginal social costs’ (Ricketts, 2000, p.ix).

? Consistent with the public choice approach to the study of government regulation is the

literature on regulatory capture. This argues that regulation is captured by the interests of the regulated and then ceases to work in favour of the general public interest, as intended (ed. Stigler, 1971 & 1988; Posner, 1974; Peltzman, 1976; High ed., 1991).a more extreme form, the argument goes that regulations from the outset are championed by special interests and are designed to maximise the utility of those interests (Stigler, 1988).

The above arguments suggest that state regulation will tend to be over-supplied. An over supply of regulation is encouraged by a lack of adequate national accounting for regulatory costs. The direct costs to government of running regulatory offices will usually be accounted for in public spending; but normally the larger costs involve the impact of regulation in terms of resulting economic distortions as well as the costs imposed on the private sector by having to comply with the regulations. These costs are often invisible or concealed and do not enter into national accounting statistics directly (Stein, Hopkins and Vaubel, 1995; Hopkins, 1995). If the bulk of regulatory costs are external, in the sense that they fall on other parties rather than the government’s budget, it is to be expected that indeed regulation will be expanded beyond its economically efficient level, i.e. where marginal social costs equal marginal social benefits.around $700bn. (for a slightly lower estimate of $660bn see Leach, 2000, p.78). This

contrasts with a figure for direct regulatory costs borne by federal agencies of some $25bn. (Hopkins, 1996 cited in Blundell and Robinson, 2000). Calculating regulatory costs is far from straight forward, however, and such estimates are necessarily rough and ready (Hahn, 1998). The dampening effects of regulation on entrepreneurship, innovation and

technological change are particularly difficult to estimate because it is difficult to say what would have been the level of economic activity in the absence of the regulation.

11 ‘Capture’ is especially likely when there is an inter-change of staff between the regulatory offices and the regulated businesses; but it can arise simply from the regulators and regulated working together on a day-to-day basis on regulatory matters. 12 In which case the externalities case for regulation, reviewed above, is turned on its head. Now regulation causes net external costs (Blundell and Robinson, 2000, p.6)).

12

Nevertheless, it seems clear that regulation has the potential to distort economic activity severely. It also has the potential to crowd out market solutions to social and economic problems. For example, in the absence of state regulations voluntary industry standards, market quality marques and private insurance might evolve to provide a superior (lower

social cost, higher social benefit) solution (for examples, albeit from developed countries and mainly the USA, see Blundell and Robinson, 2000, pp.18-29 and Yilmaz, 2000, pp.90-91). Equally, recent research on reputation and trust in market economies suggests that businesses have incentives to avoid adverse publicity relating to their activities. In particular, a large part of the value in a business may depend on a firm’s reputation for good dealing, as reflected in such things as brand value and other goodwill. It is also suggested that where the market introduces self-regulation or other forms of substitutes for state regulation (e.g. insurance), the result is much lower regulatory costs because of the resulting competition amongst

suppliers of such alternatives. Such market alternatives may also be more flexible than state regulation, in the sense of evolving in response to market signals as the economic conditions change. In which case, the removal of state controls could produce considerable net economic gain (Winston, 1993; Molitor, 1996).

In summary, reference was made earlier to the direct and indirect effects of regulation. The above discussion of state failure suggests that when assessing the economic impact of any regulation three specific sets of costs need to be included: (a) direct administrative and compliance costs falling on the private sector and public sector; (b) labour and capital costs borne by the regulatory agencies (these are usually passed on to the private sector in the form of taxation or levies); and (c) indirect costs incurred by private sector organisations and consumers as a result of both implementing the regulations and trying to avoid them. Note that the economic costs are likely to be higher in countries that have a greater respect for and compliance with the law. In these countries regulations will have more economic impact than in countries where laws are ignored.

The above arguments are generic to all types of state regulation, but further specific issues related to the setting of prices and profits arise when 'natural monopolies' are regulated.

13

2.3 The Economics of Regulating Prices and Profits

Concentrating specifically on the regulation of natural monopolies, firms can be regulated in terms of their profits or prices, as well as their quality of service. The main forms of regulation are:

? Rate of return or cost of service regulation: used extensively in the USA and elsewhere. This form of regulation establishes a satisfactory or ‘normal’ profit or rate of return on the firm’s regulatory asset base after allowing for efficient capital and operating costs. While not exactly guaranteeing a given profit, this method of regulation is intended to be more certain in terms of the profit outcome than would be the case under a price cap régime. However, it is also associated with cost padding and over-investment because the profit is set according to the size of the asset base (Averch and Johnson, 1962). Therefore, this type of regulation requires the regulator to police capital and operating costs to ensure that they are not ‘padded’ (Kahn, 1988, pp.47-112). It also requires agreement on the cost of capital to establish a satisfactory or normal profit rate. In the US the process is facilitated by public and quasi-judicial hearings at which producers, consumers, the regulatory office and other interest parties can present evidence (Sidak and Spulber, 1997).

? Price cap regulation was recommended by Professor Stephen Littlechild (1983) to the government to regulate the first privatised utility in the UK, British Telecom. It has since been adopted in the UK for the other privatised ‘monopolies’, namely gas, airports, water, electricity, and the railways, and has been copied world-wide. For example, in recent years there has been a movement away from rate of return regulation towards price cap regulation in US telecommunications (Braeutigam and Panzar, 1993).

Price cap regulation has been favoured because, properly applied, it provides incentives for firms to become more efficient. Lower costs of production lead to higher profits even when prices (and therefore revenues) are regulated. However, whereas price cap

regulation has been successful in stimulating efficiency in UK privatised companies, it has been associated with an adverse public reaction to some of the profits made (Parker, 1997). Also, it has not proved, as intended (Littlechild, 1983, 1988), much less complex to administer than rate of return regulation (Foster, 1992; Grout, 1997; Kay, 1996; 14

Newbery, 1997; Vass, 1999). To set the price cap regulators have been drawn into ever more detailed financial and economic modelling of the regulated businesses. The

information in these modelling exercises includes forecasts of the potential growth in the demand for services, the relationship between costs and volumes produced, the scope for productivity improvements, future input price changes (e.g. wages), the state of the current asset stock and the optimal depreciation allowance, the correct method for

allocating joint fixed assets to the regulated activities, and calculating the appropriate cost of capital (usually using the ‘capital asset pricing model’) (Armstrong, Cowan and

Vickers, 1994; Alexander and Irwin, 1996; Vass, 1997, 1999). These are much the same considerations as enter into the setting of profits under US rate-based regulation. The same disagreements between the regulated companies and the regulators have ensued. However, whereas in US regulation there are annual disagreements, because regulated profits are set annually, in the UK the price cap is usually set for five years and therefore the scope for frequent argument is reduced.

? Sliding scale regulation (Burns, Turvey and Weyman-Jones, 1995). This is a hybrid between a price cap and rate of return regulation. Once profits rise to an agreed level in any year prices are immediately adjusted downwards. This method of regulation has the advantage of automatically sharing the benefits of efficiency gains between producers and consumers; but it has the disadvantage of introducing disincentives for management to pursue efficiencies because not all of the savings are retained by the firm. In the UK efficiency savings under a price cap can be retained by the firm until the price cap is been rejected by government in the UK (DTI, 1998).

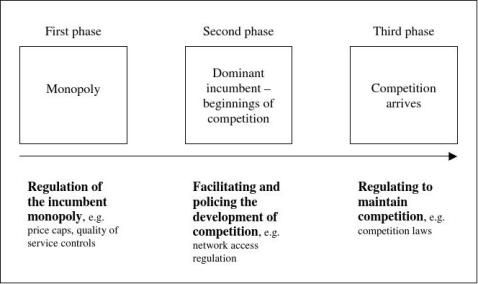

As monopoly regulation evolves, the regulator’s attention tends to turn to facilitating and policing competition. In addition to regulation of prices and profits, there will need to be regulation of network access and common carriage and interconnection charges will need to be set so as to prevent the dominant firm from inhibiting market entry (Armstrong, Doyle and Vickers, 1996). Three broad phases in the evolution of natural monopoly regulation can be identified(see Figure 2). The first phase is concerned with regulating the incumbent 13 The actual time period depends upon the length of time between the introduction of the efficiency savings and a subsequent price cap adjustment. This varies depending upon the date of the next price review and the precise method adopted to adjust the price cap.

15

monopoly, for example immediately following privatisation of a state telecom business; the second involves promoting and policing the developing competition, for example to ensure that the dominant firm does not crush new entrants to the industry; and the third phase

involves maintaining the competition. The latter stage may be best served through the use of effective national competition laws rather than dedicated industry-level regulatory offices. The length of time an industry spends in each of these phases, and whether the industry

eventually moves to the third phase, can be expected to depend upon the particular economics and technology of the industry (e.g. to what extent the conditions for ‘naturally monopoly’ do apply) and the vigour of the regulation. This raises the issue of the nature of the regulatory system and its efficiency and effectiveness.

Figure 2: Deregulation in Three Phases

2.4 Regulatory Efficiency, Legitimacy and Risk

The requisites for economically efficient and effective regulation seem to be: (a) a

willingness by government to establish the regulatory rules and then allow the regulators to operate with high degrees of discretion within these rules; (b) an economic environment which is reasonably stable so that ‘shocks’ do not provoke a change to the rules or their abandonment (more particularly, societies with high rates of inflation may have difficulty maintaining a price cap which passes higher costs on to consumers through higher prices); (c) a political system exists where a commitment to arm’s length or ‘independent’ regulation 16

carries conviction – the latter is most likely to exist where there are checks and balances in the political system to avoid abrupt policy changes and a critical media which would

embarrass a government that reneged on the regulatory contract; and (d) a political system exists where there is a track record of establishing effective ‘independent’ agencies (Parker, 1999b, 1999c). In the absence of these conditions, a commitment to regulatory rules on the part of a government may lack credibility on the part of investors. It may also prove difficult to recruit individuals with the appropriate skills and experience to become effective

regulators. Each country’s regulatory system will reflect the peculiar economic, political and social conditions into which it is introduced. In some countries separation of regulation from day-to-day politics may be problematic, especially where prominent politicians and government supporters expect to be appointed to positions of regulator.

Peter Evans has written that “.... exogenous inspirations.... build on indigenous institutional foundations...” (Evans, 1995, p.243).The institutional context is now recognised by

economists as being critical to any explanation of economic performance. Institutions act as the rules of the game and are the result of cumulative learning through time. They are reflected in the ideology, beliefs and mind set of society. One of the leading advocates of ‘institutionalism’ is the American economist Douglass North (North, 1990, 1991). North defines the term institution widely to include any constraint that individuals devise to shape human interaction (North, 1990, p.4). Therefore, institutions include formal constraints, notably laws, constitutions and rules, as well as informal constraints such as norms of

behaviour, customs and conventions (including tradition and trust relationships; on the role of trust in economies see Fukuyama, 1995; De Laat, 1997; on the related importance of that they are a product both of social, economic and political history and current conditions and that they determine the context within which, inter alia, economic transacting occurs. Countries with weak governments and judiciaries and with histories that have not promoted trust relationships are likely to face higher regulatory costs. In these countries decisions may be made behind closed doors and in response to political influences and even outright corruption. Regulatory capture will be a constant threat.

14 In this context, trust may be both facilitated and damaged by regulations and schemes such as PPPs (public-private partnerships), depending on the forms regulation and PPPs take (Parker and Hartley, 2001). Trust places the emphasis on values rather than rules, on mutually beneficial behaviour rather than regulatory contracts.

17

Establishing a proper governance structure for regulation requires addressing the political and economic environment in which the regulation is to be established (Bradbury and Ross, 1991; Kilpatrick and Lapsley, 1996; Parker, 1999b, 1999c, 1999d). A populist model of regulation emphasises democratic control and public accountability; the result is a proceduralist

approach to regulatory legitimacy requiring public accountability (through the legislature), formal rules, appointment of regulators by elected officials and judicial review, to reinforce democratic control. However, a popularist model may be less appropriate than a substantive model when assessing a country’s regulatory system. Substantive legitimacy is associated with a desire for policy consistency, expertise in solving problems, protection of diffuse interests and clear definitions of objectives and power limits, which may be missing when regulation is under direct political control (Majone, 1996).

The substantive model is most likely to be appropriate where regulation is concerned primarily with issues of ‘economic efficiency’ and preferably to circumstances where the resulting resource allocation is Pareto optimal. Arguably, regulation which involves issues to do with income and wealth redistribution or other social or environmental objectives is more appropriate to a proceduralist regulatory system, with its emphasis on democratic

accountability. It is usually not possible, however, to draw a clear distinction between

economic efficiency and distributive issues. For example, it has not proved possible for UK regulators neatly to separate the pursuit of economic efficiency from the social consequences of their decisions (Baldwin and Cave, 1999, pp.80-81). For this reason regulatory legitimacy requires a blending of proceduralist and substantive principles.

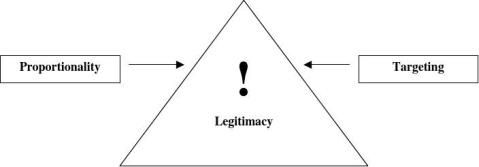

The legitimacy of a regulatory system is associated with public confidence and is dependent upon proper accountability, transparency, proportionality, targeting and consistency – what Lord Haskins chair of the UK Better Regulation Task Force calls the ‘five principles to determine the relevance and effectiveness of the regulation’ (Haskins, 2000, p.60) – see Figure 3.

18

Figure 3: Regulatory Legitimacy

Accountability

Transparency Consistency

? Accountability means that regulators, while having a large degree of day-to-day operational independence, work within clearly agreed rules and are accountable for their actions. Regulators should be required to justify their decisions both to the industries and to the general public (e.g. through Parliament) (Graham, 1995).

? Transparency requires that all relevant parties are involved in the process by which regulatory decisions are reached and that the way regulatory decisions are made is open and subject to public scrutiny.

? Proportionality means that the regulation should be proportional to the market failure to be tackled – the regulations should not be excessive in relation to the problem.

? Targeting refers to ensuring that regulations are properly aimed at the problem and do not spill over into unintended areas.

? Consistency requires a high level of uniformity and continuity in regulation so as to avoid unpleasant surprises for investors, to develop trust between regulated, regulator and the public, and therefore to minimise regulatory risk.

Where regulation lacks proper accountability and is non-transparent, disproportional, poorly targeted and inconsistent then regulatory costs will rise and the regulation is unlikely to maintain legitimacy or general public acceptance. The form of the regulation is, therefore, crucial in determining regulatory efficiency. For example, it can be shown that under certain 19

regulatory conditions the public sector may be a more efficient provider of public services than privatised, regulated businesses (de Fraja, 1993; Willner and Parker, 2000).

Experience reveals that regulation is a complex balancing act between advancing the interests of consumers, competitors and investors, while promoting a wider, ‘public interest’ agenda. More specifically, the regulator needs to balance

? minimum prices to benefit the consumer (maximise consumer surplus);

? ensure adequate profits are earned to finance the proper investment needs of the industry (earn at least a normal rate of return on capital employed);

? provide an environment conducive for new firms to enter the industry and expand competition (police anti-competitive behaviour by the dominant supplier);

? preserve or improve the quality of service (ensure higher profitability is not achieved by cutting services to reduce costs);

? identify those parts of the business which are naturally monopolistic (statutory monopolies that are not necessarily justified in terms of either economies of scale or scope);

? take into consideration social and environmental issues (e.g. when removing cross-subsidisation of services).

Achieving an acceptable balance between these regulatory objectives is never likely to be easy and for this reason regulators can expect criticism, as public attention focuses on one objective over another (Souter, 1994).

General discontent with the regulatory system is most likely to occur, however, when it is perceived that the regulator is acting arbitrarily or where, over time, a regulator is seen to favour one group in society over another. Firms operating in market economies face the usual commercial risks (changes in demand, new competition, higher input costs etc.), but regulated companies face additional risk – ‘regulatory risk’ - arising from uncertainties

associated with regulation. Regulatory risk arises from the nature of the regulatory rules (the degree of inherent risk implied by the form of regulation adopted) and uncertainty about the interpretation the regulator may place on the rules. In other words, regulatory risk arises from the information asymmetries inherent in regulation (Parker, 1998b). The regulator and the regulated companies have different levels of information. For example, having invested, the 20

regulated companies can suffer from ‘hold up’ by the regulator (Hart and Moore, 1988). The regulator could drive prices down towards the short-run marginal cost of production leading to regulated companies suffering financial losses. The companies will be unable to exit the industry in response to short-run losses where there are high fixed costs fixed costs sunk in the business.

Experience suggests that to minimise regulatory risk and maximise regulatory effectiveness:

? the rules of the regulation game need to be set down clearly for regulators and the regulated, preferably by statute;

? to protect their ‘independence’ from special interests regulators should not be open to summary dismissal (in the UK regulators are appointed under fixed-term contracts, normally for five years in the first instance, and cannot be dismissed in the meantime except for improper behaviour, as defined by legislation);

? appointments to regulatory bodies should be on the basis of ability and not the result of political patronage (UK regulators are selected by Ministers but have considerable independence from government after appointment);

? the regulators need to be adequately resourced - regulatory offices should be staffed in terms of the required skills (notably economic, financial and engineering expertise). They should have adequate budgets to attract and retain appropriate staff by paying competitive wage rates and to finance their proper functions, while maintaining their independence. This may involve separating the office’s budget from direct political control. This is

particularly important because, where regulators’ budgets are a political decision, capture of regulation by politicians is more easily achieved, indeed it may be inevitable. In the UK, budgets are linked to licence payments by regulated companies and there has been no case of a government attempting to alter a regulator’s budget to gain influence.

Under a well-functioning regulatory structure, whatever its precise form, there should be scope for regulators to use their judgement and there should be scope for ‘discovery’ and ‘learning’ as the markets change and adapt (Burton, 1997). But at the same time, a well-functioning regulatory structure avoids high levels of regulatory regulatory risk. The

objective of regulation should be to protect the consumer, while providing an environment where the industry can invest with a high degree of confidence that profits legitimately made 21

are not eroded by vexatious regulation. Where this balance is not achieved, regulation is more likely to seriously damage business development.

2.5 The Impact of Regulation on Business

Regulation influences the nature of the markets that evolve. Instead of resources being attracted to areas of greatest need, with potentially the highest welfare gains, they will be attracted to areas where access is permitted or short-term profit is highest given the regulatory constraints. This means that regulated industries operate in a different external environment to other privatised firms. Managers in privatised, regulated companies must manage their businesses in the face of both normal commercial risk and regulatory risk. Regulation can be viewed as a game played out over time between the regulator and the regulated company (Veljanovski, 1991; Hall, Scott and Hood, 2000). The dynamics of regulation involve both the regulator and management learning about regulation and the negotiating strategies to adopt. The regulatory offices will need to appoint staff who will take time to learn about the markets they are regulating and how the dominant companies behave (Parker, 2001). The companies will need to learn how best to manage within the new regulatory system and this may require the recruitment of new management with regulatory expertise. Regulation involves the development of trust and distrust relationships between the regulator, the regulated and the public. As Lapsley and Kilpatrick (1997, p.4) comment:

‘At the heart of the effective regulation of utilities sits the question of trust: the extent to which consumers, employees and the government can trust the individuals selected to act as regulators. In particular, the extent to which they can be trusted to discharge their discretionary powers effectively and the extent to which the regulator can trust the regulatee to act in a manner which may not exploit any advantage, e.g.

informational, actual or perceived, which it has over the regulator.’

In a regulated environment the distribution of efficiency gains between profits to producers (‘producer surplus or economic rent) and lower prices and improved services to consumers (‘consumer surplus’) relies heavily on the actions of the ‘regulator’. In particular, in

monopoly markets regulation is a form of proxy competition with the regulator attempting to achieve allocative and technical efficiency in the industry in the absence of competition.

Where regulation is associated with privatisation of state industry, the state’s role is altered to one of establishing the regulatory framework or ‘the rules of the game’. Management then 22

manages the enterprises within the regulatory rules. This leads to a change in the operating environment for the management of the utilities. Previously they were accountable to

government and subject to final decisions being made politically. Privatised, the management are now accountable to new stakeholders in the form of shareholders and private loan creditors (the capital market) and the new regulatory agencies. They may also face a more dynamic and hostile competitive market for their outputs (ed. Prokopenko, 1995).

These changes in the operating environment can be expected to have a profound effect on management orientation, structures and processes (Dean, Carlisle and Baden-Fuller, 1999). Changes in the external competitive environment can be expected to lead to internal changes, including a realigning of business strategy (Wolf, 1977). Managers will need to

reconceptualise the basis on which they do business and develop appropriate mental models and business strategies (Hosein, 1999; Parker, A.F, 2001). A privatised company will need to learn how to operate now that it is no longer directly accountable to a government department (or part of a government department). This requires new networks of relationships to be developed: ‘The institutional change brought about by privatization has the effect of

reshaping sectoral networks and constructing fresh relationships between established actors’ (Dudley, 1999, p.53). In other words, it involves formulating new frames of reference

involving new resource dependencies and a ‘reframing’ of strategic orientation and priorities. This can extend to an attempt to change the ‘culture’ within the organisation away from public sector ways of operating, involving a complete review of management needs,

operational goals, organisational structure, nature and location of the business, reporting and internal communication, and human resource management policies (Parker, 1995a & 1995b). There may be a need for new leadership alongside new methods of remunerating staff (more performance related), financial restructuring and new financial systems (Andrews and Dowling, 1998). There may be a reassessment of what is the ‘core business’ (Kashlak and Joshi, 1994) and what are the organisation’s ‘core competencies’ with implications for strategic positioning (Miles and Snow, 1978; Ghobadian et al., 1998).

Interestingly, however, as Reger, Duhaime and Stimpert (1992) note, deregulation has so far attracted little empirical attention from strategic management and organisational behaviour researchers. Very little is known in detail about how regulation and deregulation affect strategic choices, such as on risk profiles, products and services offered, geographical

coverage and product diversification (McGuinness and Thomas, 1997) or how they impact on 23

management style. Other unanswered questions include to what extent the pace of

deregulation matters (Mahon and Murray, 1981) and how regulation and market liberalisation impact on the ‘key success factors’ or ‘strategic drivers’ in particular industries? It may be expected, however, that the impact of regulation and deregulation measures in developing economies will be affected by why and how the policies are introduced. This turns attention to the nature of ‘policy transfer’.

2.6 The Nature of Policy Transfer

There is a growing literature on policy transfer (for a review see Bennett, 1992; Dolowitz and Marsh, 1996) or what is sometimes called ‘lesson drawing’ (Rose, 1991, 1993). Policy transfer is the process by which a country imports policies and programmes from another country or countries. Transfer is seen in terms of a wider economic and social “globalisation” in which both economic values and policies transfer mainly from the industrial economies of North America and Europe to the rest of the world. In this transfer process, policies are usually justified in terms of perceived social and economic need and are supported by fashionable ideas and theories. Looking specifically at economic regulation of privatised monopolies, the chief model in the 1980s was the UK’s privatisation programme and to a lesser extent the experience of Chile beginning a few years earlier.

In the policy transfer literature there are three main forms of transfer which together lead to the process by which ideas are transferred and policies shaped globally (Dolowitz and Marsh, 1998). The first involves coercive policy transfers, where countries are in some sense

compelled to adopt policies even if against their better judgement. Particularly since early the 1980s, loans from the World Bank and IMF have often been contingent upon governments reducing state spending and pursuing market liberalisation measures. The second form of policy transfer is normative in nature and arises from political and economic interactions between nations. It is in this context that the role of the economic theories discussed earlier (property rights, public choice etc.) in spreading attitudes sympathetic to private over state ownership are potentially important. US and to a lesser extent UK universities attract large numbers of economics students from other countries who are likely to be exposed to these theories. Those students who study at home universities are almost certain to use American and perhaps British economics textbooks and journals and may be taught by faculty trained in economics in US and UK universities.

24

The third form of policy transfer is mimetic. As more and more economies privatise their industries and deregulate markets, so there becomes more pressure on those countries still without such policies to conform (DiMaggio and Powell, 1991; Bennett, 1992; Dolowitz and Marsh, 1996). In essence, there is a powerful demonstration effect: ‘When there is general international agreement upon the definition of a problem or a solution, nations not adopting this definition or solution ….. face increasing pressure to join the international community in implementing similar programmes or policies’ (Dolowitz and Marsh, 1998, p.42). Or as Christopher Hood writes in his analysis of policy reversal: ‘... there is a sense in which, once one powerful player changes course with at least apparent success, others come under

pressure to follow suit’ (Hood, 1994, p.9) It has been suggested that international comparison produces a trend towards policy homogeneity across states (Ikenberry, 1990, p.101; North, 1990).

It is apparent, however, that there are different speeds of policy assimilation and diffusion and different forms of precise policy outcome, even extending to different interpretations of the meaning and scope of terms such as deregulation and privatisation. In other words, regulation and de-regulation should not be viewed as a posting of a set of specific policies from one country to another. Instead, it should be seen in terms of the acceptability of the policy in each host country and the way in which each country interprets and operationalises the policy (Parker, 1994, 2002). In general, the introduction of both regulation and market liberalisation policies will be a highly political activity requiring careful nurturing, consensus building and compromise. Both existing and proposed policies will have “stakeholders” or interest groups, such as domestic and foreign investors, financial institutions, aid agencies, existing domestic private sector firms, multinational corporations (who may wish to invest) and management and labour (de Kessler, 1993). Each of these groups may be advantaged or disadvantaged and will need either to be ‘won over’ or at least neutralised if the policy is to be implemented smoothly. Dolowitz and Marsh (1996, p.356) in their review of policy transfer conclude that: ‘policy making is not inevitably, or perhaps even usually, a rational process.’

To minimise the possibility that a reform will collapse in the face of opposition, the domestic champions of the policy need to create and maintain strong political support, both within government and outside, perhaps in the face of resistance from those interests which expect to be disadvantaged, such as trade unions and politicians who use state intervention for 25

political patronage. Public choice theory has been influential in winning support for privatisation and market liberalisation policies, but there is a clear paradox when the implementation of reform is considered. Why should politicians, government officials, managers etc. give up the rents they gain from the status quo? In practice, there is an innate tension within any economic reform programme between the forces for change and those opposed to change, with the latter willing to invest resources up to the value of the rents they receive from state ownership in opposition (Tullock, 1967). This will be most evident in societies where rents are large, such as societies with endemic political patronage or ‘clientism’. Equally, those who may gain rents from the introduction of reforms can be expected to invest in support of privatisation resources up to the value of their expected rents.

In looking at the formulation and implementation of organisational strategies certain “paths of change” have been identified (McWhinney, 1992). These paths take the form of (1) analysis and rational action, for example, a process of theory development and empirical testing; (2) participative, resulting from action and pressures brought by individuals and groups participating in the change process or affected by it - this can take democratic (value consensus) and non-democratic (minority pressure group) forms; (3) charismatic, the result of a strong leader or leaders with a mission - this introduces the role of “human action”; and

(4) emergent, in which a policy emerges gradually with the growing acceptance of an idea over time.

Regulation and deregulation programmes may involve rational analysis, e.g. a cost-benefit study, or instead they may result more from participative forces such as pressure groups, or simply emerge as de facto policy in the face of social, political or economic pressures (e.g. budgetary crises). In some (many?) cases the policy can be expected to result from a combination of causes. But to be placed on the political agenda and for the reforms to succeed in navigating the political process, championing by a small group (the charismatic path) may be crucial. In the UK, Margaret Thatcher championed some privatisations in the face of opposition not only from expected quarters such as the Labour Party and the trade unions, but from within her own party. In sum, where the status quo is well embedded, the 15 Technically, in both cases it will be the discounted value of the rents where the rents are earned over time.

26

study of policy transfer needs to address the conditions required to achieve successful policy reversal (Hood, 1994).

3. THE RESULTING RESEARCH ISSUES

The aim is to develop research that studies the relationship between regulation and public policy in developing countries, while drawing on the experiences of developed economies where relevant. To date most of the research on regulatory systems, including mechanisms such as price caps, has focussed on the experiences of developed economies, especially the USA and UK. Developing economies, however, often have less well-developed political traditions, less well-developed communication and information systems (IT and accounting systems) and perhaps fewer personnel within government knowledgeable about regulatory economics. The research programme will be concerned with both theory development and policy issues in regulation and with capacity building in developing countries. The research agenda is consistent with recent documents published by DFID highlighting those areas of economic regulation that are of particular concern.

It is intended that the following subjects or issues will be studied during the research programme:

? State and market interactions in the context of market liberalisation policies.

? The process and content of regulatory reform in developing countries. To what extent does institutional over-design strangle regulatory reform? To what extent are investment advisors and consultants recommending unduly complex and technical solutions (perhaps to boost their fee income)?

? The nature of regulatory governance and legitimacy in the context of developing

economies including the impact on different ownership forms, namely large enterprises (with or without FDI), co-operatives, SMEs and micro-enterprises.

? The optimal institutional structures for efficient and effective regulation in developing countries, including the applicability of ‘independent’ regulation and the relative benefits of different governance structures, including the use of multi-utility regulators, quasi-government agencies, etc. with the aim of achieving regulatory legitimacy.

? The application and limitations of particular regulatory regimes, including price caps, rate of return and cost of service regulation, within the context of the institutional structures of developing countries.

27

? The impact of different regulatory price structures on economic incentives (allocative and productive efficiency) and poverty reduction (cross-subsidisation, life-line pricing, etc.). ? ‘Policy transfer’ to developing countries in the field of economic regulation and implications.

? The nature and scale of producer and consumer representation and whether there is a participatory deficit in particular countries; this will include studying the impact of regulation and market liberalisation on both the distribution of property rights and enterprise corporate governance structures.

? The relationship between efficient and effective regulation and macroeconomic stability ? The economic sectors in which regulatory reform has so far worked best and the constraints on reform that exist in other sectors. Is there a pattern across the countries studied and how different is the experience of developing countries from those of the developed world?

? The particular conditions that promote ‘regulatory capture’ in developing countries and the policies that might be adopted to minimise the risk of capture. For example, are full-time or part-time regulators more likely to avoid capture? Does direct parliamentary scrutiny promote or reduce the chances of capture? Are multi-utility regulatory offices better able to ward off capture and develop the necessary regulatory skills than single-industry regulators?

? The ways in which economic regulation affects business strategies including

employment, capital raising, vertical integration, the performance and nature of supply and value chains, input prices, procurement etc..

? The role of economic regulation in the development of telecommunications and other economic infrastructure, e.g. ports, airports, postal services, water and energy supplies. ? Cataloguing regulatory systems in a range of developing countries, highlighting

commonalities and differences (including the types of price or profit regulation used, the methods by which regulators are appointed and dismissed, and the methods by which regulatory budgets are set). There is currently a lack of information on the nature of regulatory régimes in developing countries.

? Country and regional case studies of economic regulation and deregulation, so as to foster a wider understanding of the peculiar nature of regulation and market liberalisation in the context of developing countries.

28

? The link between economic regulation and competition policy and the need for capacity building in both areas. To what extent do existing regulations promote or inhibit

competition?

? The impact of regulation and deregulation on the economic performance of industries, sectors and enterprises, including productivity and cost function studies. The methods adopted will largely be determined by data availability, but ideally both stochastic and non-stochastic modelling techniques will be used.

? How investors protect their investments in a regulated environment.

? The impact of economic regulations on investment and fund raising, the cost of capital, and innovation and technical change.

? How the different regulatory rules at international, national and local levels interact.

? The interrelationship between economic regulation and sustainable development, poverty alleviation and social and environmental goals.

? To build on the economic literature on regulation to develop a model of optimal economic regulation for a developing country.

? Capacity already existing in developing countries to establish efficient and effective

regulatory structures, including existing regulatory knowledge and the skills base that can be tapped to man regulatory offices. Provide recommendations for capacity building including specific training needs

4. CONCLUSIONS

The main literature on regulation is based on theory development in and empirical evidence of developed economies and especially the US and UK. The next important step in the

research agenda will be a thorough review of the regulation literature specifically relating to developing economies. The next stage will then be to assess what are the important

differences between theory and practice of regulation in developed and developing countries. This will require not only a comparison of the two sets of literature, but field-work studies involving an assessment of the practice of regulation in a range of low-income countries. The intended result is a richer resource base for researchers, involving both case studies of regulatory practices in developing economies and enhanced theory development, perhaps involving the building of a completely new theory of regulation - a theory of regulation that is more applicable to such countries than the dominant regulation paradigms derived from the developed countries’ experiences.

29

REFERENCES

Adam, C., Cavendish, W. and Mistry, P.S. (1992) Adjusting Privatization, London: James Currey.

Aharoni, Y. (1986) The Evolution and Management of State Owned Enterprises, Cambridge, Mass.: Ballinger.

Akerlof, G.A. (1970) ‘The Market for “Lemons”: Quality, Uncertainty, and Market Mechanism’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol.84, pp.488-500.

Alexander, I. and Irwin, T. (1996) “Price Caps, Rate-of-Return Regulation and the Cost of Capital”, Private Sector, September, pp.25-28.

Andrews, W.A. and Dowling, M.J. (1998) ‘Explaining Performance Changes in Newly Privatized Firms’, Journal of Management Studies, vol.35, no.5, pp.601-617.

Armstrong, M., Cowan, S and Vickers, J. (1994) Regulatory Reform: Economic Analysis and British Experience, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Armstrong, M., Doyle, C. and Vickers, J. (1996) ‘The Access Pricing Problem: a Synthesis’, Journal of Industrial Economics, vol.44.

Arrow, K. (1970) Social Choice and Individual Values, New Haven: Yale University Press.

Arrow, K. (1974) The Limits to Organization, New York: Norton.

Astbury, S. (1996) “Malaysia: Sorting out the Sell-offs”, Business Asia, vol.32, no.4, pp.38-40.

Averch, H. and Johnson, L. (1962) ‘Behavior of the Firm under Regulatory Constraint’, American Economic Review, vol.52, pp.1052-69.

Baldwin, R. and Cave, M. (1999) Understanding Regulation: Theory, Strategy and Practice, Oxford: Oxford UP.

Bennett, C. (1992) What is Policy Convergence and What Causes It”, British Journal of Political Science, vol.21, pp.215-33.

Blundell, J. and Robinson, C. (2000) Regulation without the state… The Debate Continues, Readings 52, London: Institute of Economic Affairs.

Boycko, M., Shleifer, A. and Vishny, R.W. (1996) ‘A Theory of Privatisation’, Economic Journal, vol.106, March, pp.309-19.

Bradbury, R. and Ross, D.R. (1991) Regulation and Deregulation in Industrial Countries: Some Lessons for LDCs, Washington D.C.: World Bank.

Braeutigam, R.R. and Panzar, J.C. (1993) ‘Effects of the Change from Rate-of Return to Price-Cap Regulation’, American Economic Review, vol.83, no.2, pp.191-97.

30

Buchanan, J.M. (1960) Fiscal Theory and Political Economy, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Buchanan, J.M. (et al.) (1978) The Economics of Politics, IEA Readings 18, London: Institute of Economic Affairs.

Burns, P., Turvey, R. and Weyman-Jones, T.G. (1995) ‘Sliding scale regulation of monopoly enterprises’, CRI discussion paper 11, London: Centre for the study of Regulated Industries.

Burton, J. (1997) ‘The Competitive Order or Ordered Competition?: The ‘UK model’ of utility regulation in theory and practice’, Public Administration, vol.75, no.2, pp.157-88.

Cook, P. and Kirkpatrick, C. eds. (1988) Privatisation in Less Developed Countries, Brighton: Wheatsheaf.

Cook, P. and Kirkpatrick, C. eds. (1995) Privatisation Policy and Performance: International Perspectives, London: Prentice Hall.

Cook, P. and Minogue, M. (1990) “Waiting for Privatization in Developing Countries”, Public Administration and Development, vol.10, pp.389-403.

Cox, A., Harris, L. and Parker, D. (1999) Privatisation and Supply Chain Management: On the effective alignment of purchasing and supply after privatisation, London: Routledge.

Cullis, J.G. and Jones, P. (1987) Microeconomics and the Public Economy: A Defence of Leviathan, Oxford: Blackwell.

de Fraja, G. (1993) ‘Productive efficiency in public and private firms’, Journal of Public Economics, vol.30, pp.15-30, ; reprinted in (ed.) D. Parker (2001) Privatisation and Corporate Performance, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

de Kessler, A.S. (1993) “Privatization of the Enterprises of the Argentine Ministry of Defense”, Columbia Journal of World Business, vol.28, no.1, pp.133-43.

de Laat, P. (1997) ‘Research and Development Alliances: Ensuring Trust by Mutual

Commitments’ in M. Ebers (ed.) The Formation of Inter-Organizational Networks, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dean, A., Carlisle, Y. and Baden-Fuller, C. (1999) ‘Punctuated and Continuous Change: the UK Water Industry’, British Journal of Management, vol.10, special issue, pp.S3-S18.

DFID (2000) DFID Enterprise Development Strategy, 13 June, London: Enterprise Development Department, Department for International Development.

DiMaggio, P. and Powell, W. (1991) “The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organization Fields”, in eds.W. Powell and P. DiMaggio, The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

31

Dolowitz, D.P. and Marsh, D. (1996) “Who Learns from Whom: a Review of the Policy Transfer Literature”, Political Studies, vol.44, no.2, pp.343-57.

Dolowitz, D.P. and Marsh, D. (1998) “Policy Transfer: A Framework for Comparative Analysis”, in M.Minogue,C.Polidano and D.Hulme eds: Beyond The New Public

Management:Changing Ideas and Practices in Governance, Cheltenham, Edward Elgar, pp.38-58

Downs, A. (1957) An Economic Theory of Democracy, New York: Harper.

DTI (1998) A Fair Deal for Consumers: Modernising the Framework for Utility Regulation. The Response to Consultation, London: Department of Trade and Industry.

Dudley, G. (1999) ‘British Steel and Government since Privatization: Policy ‘Framing’ and the Transformation of Policy Networks’, Public Administration, vol.77, no.1, pp.51-71.

Dunleavy, P. (1991) Democracy, Bureaucracy and Public Choice, Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Evans, P. (1995) Embedded Autonomy: States and Industrial Transformation, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Financial Times, 5 January 2001, p.11: “ADB adds battle with poverty and profit and loss account”.

Foster, C.D. (1992) Privatization, Public Ownership and the Regulation of Natural Monopoly, Oxford: Blackwell.

Fukuyama, F. (1995) Trust: the social virtues and the creation of prosperity, New York: Free Press.

Fundanga, C.M. and Mwaba, A. (1997) “Privatization of Public Enterprises in Zambia: an Evaluation of the Policies, Procedures and Experiences”, paper presented at the Conference on Public Sector Management for the Next Century, Institute for Development Policy and Management, University of Manchester, 29 June-2 July mimeo.

Ghobadian, A., James, P., Liu, J. and Viney, H. (1998) ‘Evaluating the Applicability of the Miles and Snow Typology in a Regulated Public Utility Environment’, British Journal of Management, vol.9, S71-S83.

Graham (1995) Is there a Crisis in Regulatory Accountability? Discussion Paper 13, London: Centre for the Study of Regulated Industries.

Grout, P. (1997) “The Foundations of Regulatory Methodology: the cost of capital and asset values”, paper presented at the CRI Conference, The Financial Methodology of

‘Incentive’Regulation - Reconciling Accounting and Economics, London, 5 November.

Hahn, R.W. (1998) ‘Policy Watch: Analysis of the Benefits and Costs of Regulation’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol.12, no.4, pp.??

32

Hall, C., Scott, C. and Hood, C. (2000) Telecommunications Regulation: Culture, chaos and interdependence inside the regulatory process, London: Routledge.

Hanke, S.H. ed. (1987) Privatization and Development, San Francisco: ICS Press.

Harris, L., Parker, D and Cox, C. (1998) ‘UK Privatisation : its impact on procurement’, British Journal of Management, vol9, special issue, pp.S13-S26.

Hart, O. and Moore, J. (1988) ‘Incomplete Contracts and Renegotiation’, Econometrica, vol.56, pp.755-85.

Haskins, C. (Lord) (2000) ‘The Challenge to State Regulation, in J. Blundell and C. Robinson, Regulation without the state… The Debate Continues, Readings 52, London: Institute of Economic Affairs.

High, J. ed. (1991) Regulation: Economic Theory and History, Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

Hood, C. (1994) Explaining Policy Reversals, Buckingham: Open University Press.