开始新的大学征程(听萨如拉教授讲座观后感)

开始新的大学征程

听萨茹拉教授《大学,人生历练的场所》的总结

很幸运在江西理工大学应用科学学院(黄金校区)的“金沙湾”讲坛听到了萨老师的讲座,听完讲座,感觉血液都开始沸腾了。在大学一年级听这么一场讲座是很有用的,更是很及时的。大学一年级的上学期还有一个多月就要结束了,不得不说,在过去的三个多月里我好像什么都没做,但时间却在眨眼间消失了。

12月8日,我的日程是这样安排的,先去学术报告厅听萨老师的讲座,然后再去图书馆制定自己的大学计划。巧合的是萨老师在讲座中也讲到了大学要有目标,要去给自己的大学生活制定一个计划,并告诉我们这样做的重要性和必要性。也许是巧合,也许是幸运,更或是如稻盛和夫在《活法》中写道的“如有神助”,我本来打算在听完讲座之后,就去图书馆写自己的大学计划,刚好在这之前,萨老师就在讲座中讲到了这一点,而且我还幸运的问了萨老师“计划应该如何去写”,这个问题得到了萨老师用心的回答,并且萨老师还拿出自己的“效率手册”给我看。

也许真是“如有神助”吧,在听完讲座后,我立马跑到图书馆开始计划自己的大学生活,我更加坚定了自己的考研梦,并写下了目标,以及实现目标的计划。

萨老师给我留下了平易近人的印象,在讲座结束之后还亲切的与同学们合影。在“金沙湾”讲坛听了许多次讲座,萨老师的讲座无疑是最精彩的讲座之一。也许是因为洪战辉老师的那场讲座我没有把握好提问的机会。这次萨老师的讲座,我鼓足了勇气参与了互动,并在提问环节向老师提了一个问题。萨老师的回答对我来说是很重要,很有用的,因为听完萨老师的回答,我把从开学前就该写好的大学计划一口气写完了,因为我对创造自己的未来更有信心了。

萨老师的讲座得到了同学们的一致好评,大家都认为在这个周末不睡懒觉来听讲座是值得的。听完萨老师讲座的那个下午我就和几位同学一起去实践萨老师的“把赣州玩了”,因为没有比较充分的计划,所以我们并没有去太远的地方,下午我们去了江西理工大学的本部,把本部好好的逛了一遍。

萨老师是职业生涯规划的专家,在讲座中也一直强调着职业规划的重要性,我希望自己也能够成为萨老师的徒弟,向萨老师学习职业生涯规划,为自己的职业生涯绘制一张蓝图,更要向萨老师学习乐观、积极、向上的生活态度,

听完萨老师的讲座,得到的不仅仅是一时的热血,也不仅仅是那份听完讲座后写下的大学计划,而是得到了一个新的启发,让我开始重新思考自己该如何过完大学四年,思考该如何去创造自己的未来。

我相信,这次听萨老师的讲座仅仅是一个开始,在不久的将来,我一定会再次见到萨老师,再次从萨老师那里得到新的启发,学到更多的东西!

萨老师的拉面,

20xx年12月10日星期一

第二篇:香港大学教授讲座

Corporate Governance, Regulation and Bank Performance: A

Cross-country Analysis

Li Liand Frank M. Song*

School of Economics and Finance, University of Hong Kong

Abstract

Based on the hand-collected data on internal governance mechanisms of 225 banks across 48 countries over 2004 to 2006, and the bank regulation and supervision database compiled by Barth et al. (2006), this paper assesses the impacts of internal governance mechanisms and bank regulation on bank valuation and risk-taking. We compose four internal governance indices (Board structure index, Ownership structure index, Executive compensation index and Transparency index) and a corporate governance score (CG score). We find that better internal governance boosts bank valuation. Specifically, higher board independence, higher ownership concentration, using of incentive compensation, higher level of transparency, and higher CG score are all positively and significantly related with bank valuation. We also find that the independence of supervisory agency is positively related with market value of banks; however, the restrictions on financial conglomerates and government ownership of banking system are negatively related with bank valuation. Moreover, there is evidence that the regulation policies which empower private monitoring of banks not only enhance bank valuation, but also strengthen the positive effects of internal governance on bank valuation. The results on bank risk-taking show that higher CG score reduces bank risk. Restrictions on bank activities are found to increase bank risk, however, regulation policies that empower private monitoring are found to reduce bank risk.

JEL classification: G21; G28; G32; G38

Keywords: Corporate governance; Regulation; Banking; Board independence; Ownership concentration; Executive compensation; Transparency* Corresponding author contact information: fmsong@econ.hku.hk.

Corporate Governance, Regulation and Bank Performance: A

Cross-country Analysis

1 Introduction

Recent years have witnessed an explosion of research on corporate governance (see, Shleifer and Vishny, 1997; Denis and McConnell, 2003; Gillan, 2006, for survey). Despite the general focus on this topic, relatively limited attention has been paid to the corporate governance of banks (e.g., Macey and O‘Hara, 2003; Levine, 2004; Adams and Mehran, 2005; Caprio et al., 2007; Dahya et al., 2008). This is strange, considering the fact that corporate governance of banks is not only important but also unique (Levine, 2004).

Corporate governance of banks is important for banks themselves as well as for the whole economy (Caprio and Levine, 2002). First of all, banks are corporations. Sound corporate governance is essential for banks to perform efficiently. Moreover, since banks exert a strong impact on economic development (Levine 1997, 2005), corporate governance of banks is crucial for growth and development. Banks play a central role in mobilizing social savings and channeling them to the most productive projects. Bank lending is a major source of external finance for other firms, especially in developing and emerging economies. Therefore, corporate governance is essential for bank managers to allocate social capital efficiently and to enhance the performance of the economies. Banks also play a critical role in the corporate governance of other firms (Franks and Mayer, 2001; Santos and Rumble, 2006), as creditors or equity holders of firms. Thus, it is also essential that banks themselves face sound corporate governance so that they can exert effective governance over the firms they fund.

The vulnerability of banking system further emphasizes the importance of corporate governance. Since banking system is extremely vulnerable to shocks, shortcomings in corporate governance of banks, if widespread, can destabilize the financial system and pose systematic risks to the real economy (OECD, 2006). Current financial crisis advertises the enormous consequences of poor governance of banks. It is claimed that current financial crisis can be attributed to the failures and weaknesses of corporate governance arrangements (OECD, 2009). For example, the executive compensation arrangements have led to extreme risk-taking while not punish failures, and have emphasized short-term interests while not align with the long-term nature of risk.

Not only important, corporate governance of banks is also unique. Two special features distinguish corporate governance of banks from that of other firms: opaqueness and regulation. First, banks are more opaque than non-financial firms. Although information asymmetries exist in all sectors, studies suggest that information asymmetries between insiders and outsiders are much more serious in banking (Furfine, 2001; Morgan, 2002). The greater opacity intensifies the agency problem in banking. Opaqueness makes it more difficult for diffused depositors and shareholders to monitor bank managers, makes it

more difficult to design executive compensation plans that align the interests of managers and shareholders, and makes it easier for insiders to exploit outside investors.

Second, banks are heavily regulated. Because of the importance of banks for the whole economy, as well as the high information asymmetries between insiders and outsiders, governments around the world impose an array of regulations on banks. Although regulations can be considered an additional governance mechanism, in most situations they reduce the effects of traditional corporate governance mechanisms for banks (Levine, 2004). For example, governments in many countries restrict the concentration of bank ownership, they also restrict the ability of outsiders to purchase a substantial percentage of bank shares without regulatory approval, and in some countries, there may be constraints on who can own banks (e.g., limits on ownership by non-financial or non-bank firms) (Barth et al., 2006). Deposit insurance schemes reduce the incentives of depositors as debt holders to monitor banks, and increase the incentives of bank managers to increase risk-taking. Regulation policies also restrict the competition in product markets by imposing regulatory restrictions on banks‘ entry, especially on foreign banks‘ entry (Levine, 2004).

Due to the importance of corporate governance of banks, and the uniqueness of corporate governance resulted from high opaqueness and official regulation, it is valuable to examine whether the standard corporate governance mechanisms that apply to non-financial firms also work for banks. Furthermore, although it is suggested that failures in the corporate governance arrangements contribute to the current financial crisis, the policy makers unanimously focus on the reform of regulatory framework1 and nearly ignore the role of corporate governance. Thus, it is valuable to investigate whether corporate governance mechanisms matter for banks after controlling for the possible impacts of regulations.

Two cross-country studies have examined the effects of ownership structure on bank performance (Caprio et al. 2007; Laeven and Levine, 2009). Specifically, Caprio et al. (2007) find that ownership structure and shareholder protection laws that influence non-financial firms impact bank valuation as well: larger cash-flow rights by the controlling owner and stronger shareholder protection laws increase bank valuation. Laeven and Levine (2009) find that banks with large owners are characterized by higher risk-taking than widely-held, managerially-controlled banks. Laeven and Levine (2009) also find that depending on banks‘ ownership structure, the same regulation policy can have different For example, ―Bernanke calls for broader regulations: Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke said regulators should be given broad new powers to oversee financial markets, reflecting the Fed‘s evolving view that a more aggressive government hand is needed to ensure the future safety of the financial system. Among his recommendations were tougher capital requirements for big banks…‖ (The Wall Street Journal, March 11th 2009). ―President Barack Obama on Wednesday proposed the most sweeping overhaul of the way the U.S. government oversees financial markets since the 1930s. He pushed Congress to grant the Federal Reserve and the executive branch of government vast new powers to supervise previously unregulated aspects of the economy, while reorganizing other aspects of oversight‖ (The Wall Street Journal, June 17th 2009). 1

effects on bank risk-taking. Several cross-country studies pay attention to the board of directors in banking (Andres and Vallelado, 2008; Li and Song, 2009). Andres and Vallelado (2008) focus on the board of directors of banks and find an inverted U-shaped relation between board independence and bank value. Li and Song (2009) consider the impacts of regulation policies on internal governance of banks. They find that direct official supervision reduces board independence, while promoting private sectors to monitor increases board independence of banks.

In contrast to the existing studies, which focus on either ownership structure or the board of directors, we consider more comprehensive corporate governance mechanisms, including board structure, ownership structure, executive compensation and transparency, and construct a corporate governance score (CG score) to assess the impacts of corporate governance mechanisms on bank valuation and bank risk. We also test the possible influences of official regulation as well as the interaction of regulations and corporate governance on bank performance.

We use the hand-collected corporate governance data on 225 banks in 48 countries over 2004 to 2006. We construct four corporate governance indices from fifteen governance variables by employing the method of principle component analysis. The four indices are the Board structure index, the Ownership structure index, the Executive compensation index, and the Transparency index. We then get a CG score based on the four corporate governance indices.

Our results suggest that internal governance mechanisms are important for banks even when controlling for the impacts of official regulations. Specifically, we find that higher board independence, higher ownership concentration, using of incentive compensation, and higher level of transparency all boost bank valuation when controlling for bank-level, country-level features and regulations. Furthermore, higher board independence, higher ownership concentration, using of incentive compensation are found to associate with lower bankruptcy risk. We also find that higher independence of supervisory authority enhances market value of banks, whereas higher level of restrictions on financial conglomerates and government ownership of banking system reduce bank value. Moreover, although not strong, we get evidence that regulation policies promoting private monitoring of banks not only enhance market value and reduce bankruptcy risk, but also strengthen the positive effects of corporate governance on bank valuation.

One of the main challenges for papers studying corporate governance is the endogeneity problem. Since our research is a cross-country study, we address the concerns about endogeneity by employing both bank-level and country-level instrumental variables (IV) for corporate governance measures. The results using instruments support our main findings.

We contribute to the corporate governance literature insofar as not enough studies have focused on the corporate governance of banks, despite the importance and uniqueness of it. Among the existing literature, most of the studies focus on banks in the United States. Only a few papers study the role of corporate governance in banks around the world

(Caprio et al., 2007; Andres and Vallelado, 2008; Laeven and Levine, 2009; Li and Song, 2009). While they study individual governance mechanisms (such as ownership structure and board of directors) in their papers, we provide comprehensive evidence on major internal governance mechanisms. By employing both bank-level and country-level instrumental variables, we attempt to deal with the challenge from endogeneity problem, which complements the existing studies on corporate governance.

We also contribute to the understanding of current debates on the overhaul of banking system. Although the governments extremely emphasize the needs for more stringent regulation, our results show that the differences of corporate governance qualities in board independence, ownership structure, executive compensation, and transparency significantly impact bank valuation and risk-taking even when controlling for official regulation. Excessively emphasizing the role of official regulation whereas ignoring the importance of corporate governance may be misleading, given the different effects of regulation on bank risk depending on the corporate governance structure (Laeven and Levine, 2009), and the possible impacts of regulation policies on internal governance arrangements of banks (Li and Song, 2009).

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related literature on corporate governance mechanisms. Section 3 describes our data and provides definitions of the variables used in the empirical work. Section 4 examines bank valuation and corporate governance mechanisms. Section 5 provides extensions and robustness tests. Section 6 examines bank risk and corporate governance and bank regulation. Section 7 concludes the paper.

2 Corporate governance mechanisms

Adam Smith (1776) describes that when ownership and control of corporations are not fully coincident, there is potential for conflicts of interests between owners and controllers—the agency problem. Berle and Means (1932) argue that managers pursue interests of their own rather than those of shareholders. Corporate governance is a set of economic and institutional mechanisms to induce the self-interested controllers of a corporation to make decisions that maximize the value of its owners (Denis and McConnell, 2003).

Generally, there are two types of mechanisms to resolve the conflicts between owners and controllers. One type consists of internal mechanisms, including the board of directors, the ownership structure, executive compensation, and financial disclosure. The second are external mechanisms, including the takeover market, the legal infrastructure, and the product market competition. Several facts make the internal governance mechanisms critical for banking industry. Firstly, certain external governance mechanisms, such as the takeover market and the product market competition, are nearly absent in banking (Prowse, 1997; Levine, 2004). Secondly, the pervasive regulations, especially the deposit insurance schemes, reduce monitoring of bank managers from the debt holders (Billett et al., 1998). Moreover, the main aim of the regulations is to reduce systemic risk, which might come into conflict with maximizing shareholders‘ value. The conflict

introduces a new agency problem. Thus, our paper focuses on the internal governance mechanisms. We also consider the role of official regulations in banks.

The board of directors, at the apex of internal control system, is the bridge between management and shareholders. Shareholders can exert influences on the behavior of managers through the board of directors to ensure that the company is running in their interests. Conventional wisdom suggests that more independent board of directors indicates better corporate governance. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 requires that boards have audit committees that consist only of independent outside directors. The Codes of Best Practice issued in many countries have called for greater outside representation and the separation of CEO and chairman in the board of directors (Denis and McConnell, 2003). The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) has advocated board of directors with adequate number of independent directors (Enhancing Corporate Governance for Banking Organizations, September 1999 and February 2006). The empirical results on US non-financial firms generally show that higher board independence is related to better decision on such issues as acquisitions and CEO turnover (Hermalin and Weisbach, 2003). The cross-country study by Dahya et al. (2006) demonstrates a positive relationship between board independence and firm value and a negative relationship between board independence and related party transactions. Relatively few studies have examined the effects of board independence in banking industry (e.g., Brewer III et al., 2000; Adams and Mehran, 2005; Andres and Vallelado, 2008), and the results are mixed.

Ownership structure is crucial to the value maximization of firm. Equity held by the largest shareholders and insiders can act as a governance mechanism to avoid the conflicts of interests between managers and shareholders. Shleifer and Vishny (1997) suggest that legal protection and concentrated ownership are essential for a good corporate governance system. However, ownership concentration may have either positive or negative effects on corporate governance. On one hand, concentrated ownership may solve the free-rider problem of monitoring managers. The greater control that the largest shareholders have leads them to take actions to increase firm value, benefiting all shareholders. On the other hand, concentrated ownership structure also gives the largest shareholders substantial discretionary power to pursue private benefits at the expense of other shareholders, potentially reducing firm value. Similarly, equity ownership held by insiders can align the interests of insiders with those of other shareholders, leading to higher firm value. However, higher ownership of insiders results in higher managerial control, potentially entrenching managers. The studies regarding the ownership structure and firm performance in US provide mixed results, whereas ownership concentration most often has positive effects on firm value in non-US firms (Denis and McConnell, 2003). Caprio et al (2007) demonstrate that concentrated ownership is an important governance mechanism for banking. They find that larger cash-flow rights of controlling shareholders boost bank valuation in 44 countries. Laeven and Levine (2009) find a positive relationship between ultimate cash flow rights held by the large control owner and bank risk-taking, and explain that higher ownership concentration aligns managers‘ risk-taking incentives with those of shareholders.

To align the interests of managers and shareholders, appropriately structured executive compensation, which is linked to both stock valuation and accounting-based performance measures, is necessary. Pay-performance sensitivity reflects the degree to which executive compensation aligns top executives‘ interests with those of shareholders. The vast majority of pay-performance sensitivity comes from equity-based compensation such as stocks and options (Murphy, 1999; Core et al., 2003). Many empirical studies demonstrate a positive relationship between equity-based compensation and firm value (e.g., Jensen and Murphy, 1990; McConnell and Servaes 1990; Mehran, 1995). However, some studies argue that option is a means of rent extraction if the executives have control of the board and use large option grants to extract wealth from shareholders (e.g., Core et al., 1999). Banks are reported to less likely use managerial stock options than non-financial firms (Houston and James, 1992); however, banks in US have increasingly employed stock option-based compensation after the deregulation (Crowford et al., 1995; Chen et al., 2006). Chen et al. (2006) suggest that the stock option-based compensation induces bank risk-taking.

Financial transparency and adequate information disclosure are crucial for corporate governance of firms (La Porta et al., 1998; Bushman and Smith, 2003). Sufficient, credible, and timely information regarding the firm‘s operations, financial status, and the external environment facilitates shareholders to discipline and monitor managers, enables the board of directors to enhance shareholder value by advising managerial decisions, and provides a basis for determining executive compensation plans designed to align executives‘ and shareholders‘ interests. One key to the provision of accurate information is the use of accurate accounting standards. La Porta et al. (1998) suggest that the accounting standard is an important element of corporate governance. Leutz and Verrecchia (2000) find that German firms that voluntarily adopt either International Accounting Standards (IAS) or US Generally Accepted Accounting Practices (GAAP) for their reporting show lower information asymmetry and higher stock liquidity compared with a control group of firms employing the German reporting regime. Baek et al. (2004) find that Korean firms that have higher disclosure quality suffer less in financial crisis. Transparency is even more important for banking industry since information asymmetry between insiders and outsiders is much more serious in banks than non-financial firms (Furfine, 2001; Morgan, 2002). Studies show that improving bank disclosure and transparency benefits banks as well as the financial system (e.g., Jordan et al., 1999; Tadesse, 2003). Specifically, Jordan et al. (1999) show that improving bank disclosure during a banking crisis provides conditions for market discipline to work more effectively. Tadesse (2003) provides cross-country evidence that more comprehensive, accurate, and timely bank disclosure mitigates the likelihood of a systematic banking crisis.

Banks are heavily and pervasively regulated. Regulations distinguish corporate governance of banking from other industries. Although official regulation may represent an additional governance mechanism, previous studies show that regulation practices frequently impede the effects of standard governance mechanisms. The deposit insurance reduces the incentives of debt holders to monitor managers, and thus reduces the effectiveness of market discipline (Billett et al., 1998). Restrictions on ownership structure in many countries limit the role of concentrated equity as a common internal corporate

governance mechanism (Prowse, 1997; Caprio and Levine, 2003; Macey and O‘Hara, 2003). Powerful official supervision may reduce the incentives of shareholders to monitor bank managers (Li and Song, 2009). Studies show that different regulation policies impact bank performance very differently (Barth et al., 2004, 2006; Beck et al., 2006). They find that regulation policies which force accurate information disclosure and promote private monitoring work best for bank development and stability. However, policies that rely on direct official supervision and regulation of bank activities are negatively associated with bank development and positively related to bank corruption. Lin et al. (forthcoming) demonstrate that the independence of supervisory authority and the bank accounting disclosure are positively related to the efficiency of banks; however, government ownership of banking is negatively related to bank efficiency. Caprio et al. (2007) find that regulation policies, such as the stringency of capital requirement and the official supervisory power, do not influence bank valuation.

3 Data and variables

3.1 The sample

To conduct our analysis, we build up a data set on bank corporate governance, bank valuation, bank risk-taking, and other bank specific and country specific characteristics. Information on corporate governance is particularly difficult to collect. Data permitting, we collect the corporate governance information of the 10 largest publicly listed commercial banks and Bank Holding Companies (BHCs) (as defined by the total assets at the end of 2006) in those countries covered by Barth et al.‘ (2006) database on bank regulation and supervision. The time period is from 2004 to 2006. Since many countries have fewer than 10 publicly listed banks that we can get information on corporate governance and market valuation, the final sample consists of 476 bank-year observations of 225 banks across 48 countries2. As suggested by Caprio et al. (2007), focusing on the largest banks enhances comparability across countries. Most of the countries in our sample are the same as in Caprio et al. (2007).

3.2 Sources

The corporate governance measures are hand-collected. For every bank in the sample, we collect the information of board structure, ownership structure, executive compensation, and transparency standards from 2004 to 2006. We intensively use banks‘ annual reports, proxy statements, regulated files, and websites. Also, many national institutions (e.g., Central Banks and regulatory authorities) maintain websites that we used to search for the corporate governance data.

Bank valuation, bank risk, and control variables come from the BankScope database which provides market and financial data for more than 2000 publicly listed commercial banks and BHCs. Regulation variables come from Barth et al. (2006), which are compiled based on a World Bank survey on bank regulation and supervision in 152 We drop the observations with the highest and lowest 1% market-to-book-value (MTBV) in our sample to reduce the effects of outliers on the results. 2

countries during 2001-2003. We use variables from World Development Indicator (World Bank, 2007) and La Porta et al. (1998) to control for country-level macroeconomic and the legal and institutional factors. Table 1 identifies the data sources and provides brief descriptions and definitions of the variables. Table 2 presents summary statistics of the key variables.

[Table 1 and 2 here]

3.3 Corporate governance

Corporate governance indices are the key independent variables in our study. Referring to Song and Lei (2008), Bai et al. (2004) and Gompers et al. (2003), we construct four indices (Board structure index, Ownership structure index, Executive compensation index, and Transparency index) from 15 corporate governance variables based on the internal governance mechanisms reviewed in Section 2. We use the principal component analysis3 to form our indices. Using the largest positive eigenvalue, we generate an index score with the mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1 for each of the four internal governance mechanisms. Credit Lyonnais Securities Asia (CLSA hereafter, 2001) and Gompers et al (2003) construct corporate governance index by adding one point to each variable when the variable improves corporate governance, and they get the index by summing up the points. Compared to CLSA (2001) and Gompers et al (2003), the advantage of principle component indices is that equal weights for the individual variables are not specified. A disadvantage is that it is less transparent how changes in a variable impact the index. Table 3 provides a summary of the indices and variables. Table 4 provides the mean value of the indices by county. In the following section we discuss the construction of the four internal governance indices.

[Table 3 and 4 here]

3.3.1 Board structure index

The Board structure index is constructed from four variables4. 1) Percent of Independent Non-executive Directors (INEDs)5 on the board of directors. It is the ratio of According to the Stata Reference Manual, the objective of principal component analysis (PCA) is to find the unit-length linear combinations of variables with the greatest variance. Principal component analysis finds q common factors that reconstruct the p original variables.

yij=z1i?b1j+zi2?b2j+...+ziq?bqj+eij, where,yij is the value of the ith observation for the jth variable, 3

zik is the ith observation for the kth common factor, bkj is the set of linear coefficients known as eigenvectors, and eij is the residual matrix normally distributed. The command ―score‖ creates a

new set of variables that are the estimates of the first k factors produced in principal component

???'??1x, where ? is the unrotated loading analysis. The formula of the regression score is f

matrix.

4 We check whether our sample is consistent with previous literature using board size and ratio of INEDs. The average board size (12) in our sample is lower than that of the largest commercial banks in six OECD countries (average size of 16 in Canada, France, Italy, Spain, the UK, and the

INEDs to board size as percentage. 2) Percent of INEDs on the audit committee. It is the ratio of INEDs in audit committee to the committee size as percentage6. 3) No CEO/Chairman duality. It is a dummy variable with the value of 1 if CEO is not the board chairman, 0 otherwise. 4) INED acts as the board chairman. It is a dummy variable, which takes value of 1 if an INED acts as board chairman, 0 otherwise.

We use the largest positive eigenvalue to generate the Board structure index, which varies between -2 and 2.04 with the mean of 0 and median of -0.07, and with higher value indicating higher board independence.

3.3.2 Ownership structure index

The Ownership structure index7 is constructed from four variables. 1) Percent of ownership held by the largest shareholder. It is the percentage of total issued shares held by the largest shareholder. 2) Percent of ownership held by the five largest shareholders. It is the percentage of total issued shares held by the top five shareholders. 3) Logarithm of value held by the largest shareholder8. It is the logarithm of market value held by the largest shareholder. 4) Logarithm of value held by the five largest shareholders. It is the logarithm of market value held by the top five shareholders. US) in Andres and Vallelado (2008), and is also lower than the average board size (18.1) of largest BHCs reported by Adams and Mehran (2005). However, this does not mean our sample is not representative. Andres and Vallelado (2008) cover six largest economies in the world. Adams and Mehran (2005) cover the 35 largest BHCs in the US. The large board sizes in the two papers are related to large sizes of banks. Moreover, the time periods of their samples are earlier. Bank boards are gradually decreasing in size and increasing in independence during these decades due to the conventional wisdom that smaller size and more independent boards are better ones. The average board size of banks in Canada, France, Italy, Spain, the UK, and the US in our sample is 15, which is close to the 16 directors reported by Andres and Vallelado (2008). The ratio of INEDs in our sample (50.41%) is lower than 79% (ratio of outside directors) in Andres and Vallelado (2008). However, our criterion for board independence is much stricter than. Thus, it is not unreasonable that our ratio is much lower than that of Andres and Vallelado (2008). The average ratio of outside directors of banks in Canada, France, Italy, Spain, the UK, and the US in our sample is 83.69%, which is close to Andres and Vallelado (2008). 5 Referring to Dahya et al. (2006) and following Li and Song (2009), we consider a director as independent if he is not (1) an employee of the bank (including manager, employee, representatives of employees); (2) a major shareholder (5% or more) of the bank; (3) an employee or manager of subsidiary of the bank; (4) a manager of holding company of the bank; (5) an employee or manager of bank‘s major shareholder if the shareholder is a company; (6) a close family of bank manager or major shareholder of the bank; and (7) a manager of the bank in three years. 6 Following Klein (1998, 2000), if the bank does not have an audit committee, the Percent of INEDs in the audit committee is set to 0. 7 Due to non-availability of data on insider shareholding, we only consider the concentration of ownership structure, and do not consider the ownership held by insiders (officials and directors). 8 Logarithm of value held by the largest shareholder and Logarithm of value held by the five largest shareholders reflect cash flows to the large shareholders. Shleifer and Vishny (1986) indicate that large shareholders are entitled to receive significant cash flows from the firm to cover the cost of monitoring and information gathering. The more significant cash flows the shareholders are going to receive, the more efforts they will exert to monitor the managers.

Information on the percentages of ownership held by largest and five largest shareholders comes from BankScope database. We complement the variables manually for the missing data by using annual reports and websites of banks. Values held by the largest shareholders are the products of the percentages of ownership and market values of the banks.

The Ownership structure index ranges from -2.61 to 3.27, with the mean of 0 and median of -0.02, and with higher value indicating higher ownership concentration.

3.3.3 Executive compensation index

The Executive compensation index is constructed from four dummy variables. 1) Option schemes to top executives. This dummy variable takes value of 1 if a bank employs share option schemes to top executives, 0 otherwise. 2) Option schemes to non-executive directors. Many banks also employ share option schemes to non-executive directors. The dummy variable takes value of 1 if a bank has such schemes, 0 otherwise. 3) Share-based bonus9. It measures whether there is share based bonus for top executives. It equals 1 if a bank has such bonus schemes, 0 otherwise. 4) Variable compensation. It takes value of 1 if top executives are paid variable compensation, 0 if they are paid fixed compensation.

The Executive compensation index ranges from -1.77 to 1.31 with the mean of 0 and median of 0.67, higher value indicating higher pay-sensitivity of executive compensation.

3.3.4 Transparency index

Transparency index is constructed from three variables. 1) Big 4 as auditors. It is a dummy variable, which takes value of 1 if a bank employs one of the Big 4 accounting firms (PricewaterhouseCoopers, Deloitte Touche Tomatsu, Ernst & Young, and KPMG) as their auditors, 0 otherwise. 2) Cross listing in US. This dummy variable identifies banks whose shares are traded either as a direct listing on a US stock exchange or as an American Depository Receipt (ADR). 3) Disclosure of executive compensation and shareholdings. This variable is the sum of three dummy variables which indicate whether the bank discloses information on top executive compensation, top executive shareholdings, and directors‘ shareholdings respectively. The three dummy variables take value of 1 if the bank provides corresponding information for individual person, 0.5 if the bank provides information in aggregate level, and 0 if no such information is provided. Disclosure of executive compensation and shareholdings ranges from 0 to 3, with higher values indicating better disclosure.

The Transparency index varies between -2.60 and 1.32, with the mean of 0 and median of -0.02, and with higher value indicating better transparency standard of the bank. Share-based bonus includes various share-based payments, such as options, warrants, phantom shares, deferred shares, restricted shares and so on. 9

3.3.5 Corporate governance score

We construct an overall CG score based on the Board structure index, Ownership structure index, Executive compensation index, and Transparency index. The CG score is generated by summing up the rankings of the four corporate governance indices, and then normalizing to 0-10010. The CG score gives an ordinal comparison of banks, with the mean of 45.23 and median of 44.41, and with higher value indicating better corporate governance quality.

3.4 Bank valuation, bank risk and bank controls

We use two indicators to measure bank valuation. Tobin’s Q is the traditional measure of valuation. Q is calculated as total assets minus the book value of common equity plus the market value of common equity divided by the book value of total assets. Adams and Mehran (2005) and Andres and Vallelado (2008) use this measure in their studies on board effectiveness.

Market-to-book value (MTBV) is the ratio of the market value of equity to the book value of equity. We use this valuation measure because banks are highly leveraged (Caprio et al., 2007). The average equity to total asset ratio in our sample is only 9.53 percent.

We also examine the effects of corporate governance and regulation policies on bank risk. Following Laeven and Levine (2009), we primarily measure bank risk using the z-score of each bank, which equals the return on average assets (ROA) plus the Capital-assets ratio (CAR) divided by the standard deviation of return on average assets ((ROA)) over the period 2002-200611. The z-score measures the distance from insolvency (Roy, 1952). Insolvency is defined as when losses surmount equity (E<-) (E is equity and is profits). The probability of insolvency can be expressed as prob(-ROA<CAR), where ROA equals /A and CAR equals E/A. The inverse of the probability of insolvency equals (ROA+CAR)/(ROA) if the profits are normally distributed. We define the inverse of the probability of insolvency as the z-score. Another variable that we used to measure risk is the Earnings volatility, which equals the standard deviation of the ratio of total earnings before taxes and loan loss provisions to total assets, computed over the period 2002-200612. Previous studies (Adams and Mehran, 2005; Caprio et al., 2007; Andres and Vallelado, 2008) suggest that differences in the business structure of banks may influence bank valuation and risk. We therefore control bank size (Total asset), loan growth rate (Loan growth), and CAR to account for the differences in the business structure. Bank size is measured by the logarithm of the total assets in book value. Loan growth equals the growth rate of bank‘s loan portfolio over the last three years. We use loan growth rate to We also test the CG score generated by principle component analysis, and the empirical results are similar. 11 Since the earliest financial data we can get are from 2002, we therefore only calculate the z-score for banks in 2006. 12 Similar to z-score, we only calculate the Earnings volatility ratio for banks in 2006. 10

control for differences in bank‘s growth opportunity. CAR is the ratio of bank‘s equity to total assets in book value. CAR reflects the differences in bank‘s leverage. We also add bank‘s ROA in previous year (ROA-1) to control for the effects that the investors are willing to pay premiums to banks with good performance. Our sample includes commercial banks and BHCs. Commercial banks and BHCs have different business structures, which may influence their valuation (Adams and Mehran, 2005). We add a dummy variable BHC to identify whether a bank is a commercial bank or BHC.

3.5 Bank regulations

Another set of key independent variables in our analysis are bank regulation variables. As Barth et al. (2002) show, regulation polices influence the efficiency and development of banking sector. Moreover, regulation policies also impact banks‘ internal governance structure (Li and Song, 2009). Laeven and Levine (2009) find that the same regulation policy may have different effects on bank performance depending on the corporate governance structure. Therefore, we want to examine whether internal governance mechanisms still matter for banks when controlling for regulation polices, whether and how regulation policies will impact the valuation and risk taking of banks, and whether the impacts of regulation policies depend on banks‘ corporate governance structure.

The bank regulation variables are from Barth et al. (2006). We choose the regulation policies stressed by the Basel Committee, and those highlighted by theory as affecting bank behavior. The variables used in our analysis include the Capital regulatory index, Official supervisory power index, Private monitoring index, Independence of supervisory authority, Overall activities restrictiveness, Financial conglomerates restrictiveness index, Government-owned banking, and No explicit deposit insurance scheme. Detailed definitions are given in Table 1, and Table 2 provides summary statistics. Capital regulatory index is an index of regulatory oversight of bank capital. It is constructed from nine variables, regarding whether the capital requirement reflects certain risk elements (e.g. market risk) and deducts certain market value losses (e.g. market value of loan losses not realized in accounting books, unrealized losses in securities portfolios, and unrealized foreign exchange losses) from capital before the minimum capital adequacy is determined, and whether certain funds (e.g. assets other than cash or government securities, borrowed funds) are used to initially capitalize a bank and are officially verified. Official supervisory power is an index reflecting the power of bank supervisory agency. It is constructed on the basis of 14 dummy variables, regarding whether bank supervisors can take specific actions (e.g. force a bank to change its internal organizational structure, suspend dividends, stop bonuses, halt management fees, force banks to constitute provisions against actual or potential losses as determined by the supervisory agency, supersede the legal rights of shareholders, remove and replace managers and directors, obtain information from external auditors, and take legal action against auditors for negligence) against bank management, bank owners, and bank auditors in both normal

times and times of distress. Greater bank supervisory power may inhibit insiders of the bank from exploiting minority investors.

Independence of supervisory authority is an index measuring the extent to which the supervisory agency is independent from political capture, and is protected by the legal system from capture by the banking industry. High level of supervisory independence allows bank supervisors to monitor banks in a strictly professional and consistent fashion. Furthermore, supervisory independence allows supervisors to elicit the proper level of responsiveness to the guidance, constructive criticism, and direction they give to banks (Barth et al., 2003).

Private monitoring index is constructed from nine dummy variables measuring whether bank directors and officials are legally liable for the accuracy of information disclosed to the public, whether banks must publish consolidated accounts, whether banks must be rated and audited, whether subordinated debt is allowable, and whether there is deposit insurance scheme.

No explicit deposit insurance scheme is a dummy variable indicating whether there is an explicit deposit insurance scheme, and if not, whether depositors are fully compensated last time when a bank failed. In fact, No explicit deposit insurance scheme is a sub-item of the Private monitoring index. Research shows that explicit deposit insurance exacerbates the moral hazard problem, reduces the market discipline from depositors and stockholders, and reduces the incentives of bank managers to perform prudently (Demirgü?-Kunt and Detragiache, 2002; Demirgü?-Kunt and Huizinga, 2003; Barth et al. 2004; Pennacchi, 2006). We therefore expect that No explicit deposit insurance scheme improves bank valuation and reduces bank risk.

Overall activities restrictiveness is an index reflecting the regulatory restrictions on banks from engaging in securities market activities, insurance activities, and real estate activities. Financial conglomerates restrictiveness is constructed from three variables, reflecting the degree of restrictions on the ownership between banks and nonfinancial firms. High restrictions on bank activities and financial conglomerates may reduce bank franchise value. Banks with high franchise value have incentives to exercise prudent behavior and avoid taking excessive risk that may trigger a drop in its franchise value (Keelley, 1990; Demsetz et al., 1996; Anderson and Fraser, 2000; Hellmann etc., 2000; Konishi and Yasuda, 2004). Thus, Overall activities restrictiveness and Financial conglomerates restrictiveness may reduce bank valuation and risk.

Government-owned banking is a dummy variable which measures whether 50% or more of the banking system‘s assets are owned by the government. Governments often do not have sufficient incentives to ensure socially desirable investments. They instead politicize resource allocation, soften budget constraints, and hinder economic efficiency (Shleifer and Vishny, 1998). Greater government ownership of banks is generally related to less efficient and less well-developed financial systems (La Porta et al., 2002).

3.6 Country controls

Country-level control variables account for the differences among countries in the level of economic development. We include the gross domestic product per capita (GDP per capita), real gross domestic product growth (GDP growth), and the inflation rate (Inflation) to control for the possible impacts of economic development on bank valuation and risk.

We check the correlations among the key banking variables and country-level variables. Most of the correlation coefficients are below 0.3, which means that multicollinearity is not a serious problem. For brevity, the correlation matrix is not reported here but is available from the authors.

4 Corporate governance and bank valuation

4.1 Univariate analysis

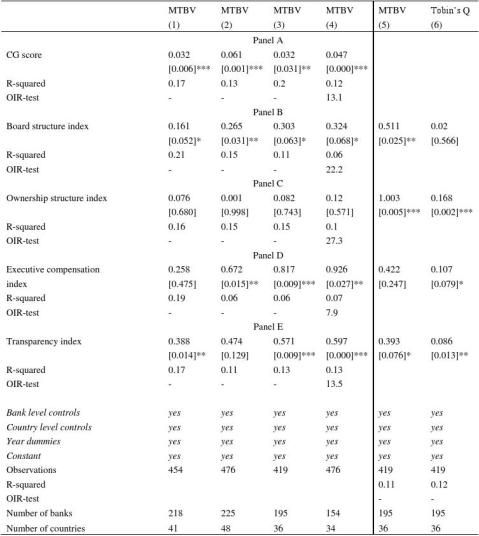

In this section, we examine the effects of corporate governance on bank valuation. Before turning to the regression results, we first summarize the association between measures of bank valuation and indicators of corporate governance using univariate analysis. The results are presented in Table 5.

[Table 5 here]

For each of the Board structure index, Ownership structure index, Executive compensation index, Transparency index, and CG score, we split the sample into banks with above-median value and below-median value, and compare bank valuation between the two groups. Panel A provides the mean MTBV and Tobin’s Q of banks in high corporate governance value groups and low corporate governance value groups. In Panel B we test whether the MTBV and Tobin’s Q differ significantly across the groups.

Banks with higher level of Board structure index have significantly higher valuation as measured by MTBV and Tobin’s Q. It is consistent with the view that high board independence enhances firm valuation. Similarly, banks with higher level of Ownership structure index, Executive compensation index, Transparency index, and CG score all have significantly higher valuations except for banks with higher level of Executive compensation index as measured by Tobin’s Q. Overall, the univariate analyses indicate that there are strong positive relationship between bank valuation and corporate governance measures.

4.2 Regression results

To assess the impacts of corporate governance mechanisms on bank valuation, we first examine the relationship between bank valuation and corporate governance indices when controlling for bank specific traits and country specific characteristics. The results

are presented in Table 6. We then examine the impacts of individual corporate governance variables, and the results are presented in Table 7.

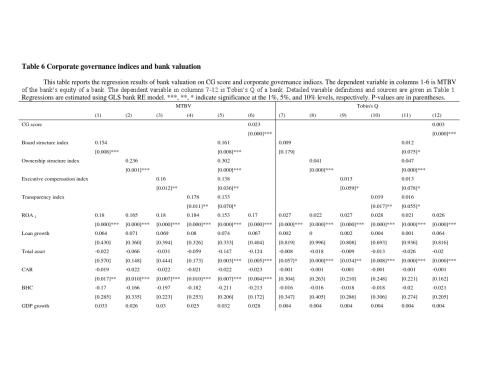

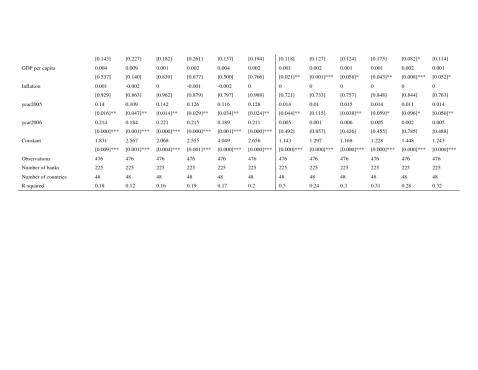

[Table 6 and 7 here]

All the regressions in this paper are estimated employing generalized least square (GLS) bank Random-Effects (RE) estimator (Baltagi and Wu, 1999), except that the regressions in Table 11 are estimated with instrumental variables using Baltagi‘s (1981) two-stage least square (2SLS) RE estimator. The GLS RE estimator is robust to first-order autoregressive (AR(1)) disturbances (if any) within unbalanced panel data and cross-sectional correlation and/or heteroskedasticity across panels. When there is unobserved bank fixed effect, panel Fixed-Effects (FE) estimation is commonly suggested (Wooldridge, 2002). However, FE estimation is not appropriate for our study for the following reasons. First, time-invariant variables such as bank regulation variables cannot be estimated with FE regression, as they would be absorbed or wiped out in ?time-demeaning‘ or ?within transformation‘ process of the variables in FE model. Second, FE regression requires significant within panel (within bank in our study) variations in the variable values to generate consistent and efficient estimates. When the important explanatory variables do not vary much over time, the FE estimates would be imprecise (Wooldridge, 2002). The corporate governance mechanisms are relatively stable for banks, and the corporate governance indices and corporate governance variables in our paper vary little over 2004-200613. Third, for large ?N‘ (i.e. 225) and fixed small ?T‘ (i.e. 3), which is the case for the panel data set (observations on 225 banks over 3 years) in this paper, FE estimation is inconsistent (Baltagi, 2005). Furthermore, FE estimation would lead to an enormous loss of degrees of freedom in case of a large ?N‘ (Baltagi, 2005). Finally, FE estimates could aggravate the problem of multicollinearity if solved with least squares dummy variables (Baltagi, 2005). Thus, we use GLS RE estimation rather than FE estimation in our paper. Breusch and Pagan‘s (1979) Lagrange multiplier tests support the random-effects specification, which strongly reject the null hypothesis that errors are independent within banks.

As discussed before, we control Total asset, Loan growth, CAR, ROA-1, and BHC dummy to account for bank specific traits. We also control country specific characteristics such as the GDP per capita, GDP growth, and Inflation. Unless indicated otherwise, we include each of these control variables in our subsequent regressions. The dependent variable in columns 1-6 of Table 6 is MTBV. In columns 7-12, we use Tobin’s Q as an alternative measure of bank valuation. In Table 7 and subsequent regressions, we always use MTBV as the measure of bank valuation14. In an unreported table of year-to-year changes in corporate governance indices and corporate governance variables, results show statistically insignificant t-statistics and Mann-Whitney z-statistics of changes of corporate governance indices and variables. 14 Although it is conventional to use Tobin‘s Q as proxy of firm valuation in non financial firms, however, as suggested by Caprio et al. (2007), it is more appropriate to use MTBV as proxy of bank valuation since banks are highly leveraged. The average equity to total asset ratio in our sample is only 9.53 percent. Moreover, what we want to examine is whether shareholders are 13

The coefficients of control variables are consistent with literature. Consistent with Caprio et al. (2007), ROA-1 enters the regressions positively and significantly, and the coefficients of Loan growth are not statistically significant. The positive coefficients on ROA-1 show that shareholders are willing to pay a premium for banks with better earlier performance. Though sometimes not significant, the coefficients of Total asset are negative, which is consistent with Durnev and Kim (2005) and Dahya et al. (2008), indicating that value decreases as firm ?size‘ increases. Coefficients on CAR are significantly negative, which is also consistent with Caprio et al. (2007) 15. The coefficients on GDP per capita, GDP growth, and Inflation are generally not significant.

4.2.1 Board structure index

The regression results in Table 6 and Table 7 indicate that higher board independence is related to higher bank valuation. As can be seen in Table 6, the coefficients of Board structure index are positive and statistically significant at the 1% level when using MTBV as proxy of bank valuation (columns 1 and 5), suggesting that increased board independence results in better corporate governance of banks. When using Tobin’s Q as proxy of bank valuation, Board structure index is significantly and positively associated with bank valuation at 10% level when simultaneously considering other corporate governance mechanisms (column 10).

The regression results of bank valuation on individual board structure variables in Table 7 (columns 2, 3, 4 and 5) are consistent with the results on Board structure index in Table 6. The positive effects of board independence on bank valuation are consistent with Durnev and Kim (2005) and Dahya et al. (2008), who provide evidence on positive relationship between board independence and valuation in non-financial firms. Andres and Vallelado (2008) show an inverted U-shaped relation between the ratio of outside directors and bank valuation, and suggest that the optimal ratio of outside directors is about 80%. Since our sample is different from Andres and Vallelado (2008), and we use the ratio of INEDs to measure board independence, it is not strange that our results are different from Andres and Vallelado (2008). The mean value of board independence in our sample is 49.78%, which means our sample mainly locates at the left side area of the inverted U-shaped curve. Thus it is reasonable there is a positive relationship between board independence and bank valuation for our sample.

The effects of board independence on bank valuation are not only statistically significant, but also economically significant. In order to demonstrate the magnitude of the impacts of corporate governance mechanisms on bank valuation, we use Model 5 in Table 6 to quantify the effects that corporate governance indices have on the MTBV of bank willing to pay a premium for better corporate governance of banks, which means we should focus on the market valuation and book value of equity instead of total assets of banks. 15 Caprio et al.‘ (2007) results show that the CAR of banks is negatively related to bank MTBV at the 1% significant level. The possible reason for the negative relationship between CAR and MTBV is that higher CAR means lower discipline from debt holders, and shareholders pay a premium for banks that are tightly monitored by debt holders.

equity. Specifically, we compute the change in MTBV due to a change in the corporate governance indices for an average bank. The empirical results are presented in Table 8.

[Table 8 here]

The estimates imply that a one standard deviation increase in Board structure index would lead bank value to increase 0.16, which is 8.94 percent of the mean value of MTBV in our sample of banks. If Board structure index increases from the minimum to maximum in the sample, bank value would increase 0.65, which is 36.4 percent of the mean value of MTBV of bank equity.

4.2.2 Ownership structure index

Table 6 shows that higher ownership concentration enhances bank valuation, implying that concentrated ownership improves corporate governance. The coefficients of Ownership structure index in Table 6 are positive and statistically significant at the 1% level in all model specifications (columns 2, 5, 8, and 11). The positive association between Ownership structure index and bank valuation is consistent with previous studies (e.g., Shleifer and Vishny, 1986; Caprio et al., 2007), suggesting that larger cash-flows of controlling shareholders will motivate them to monitor managers and boost bank value. We also add both linear and quadratic terms of ownership concentration variables in Table 7 (columns 5 and 6) to test the possible non-linear effects of ownership concentration on bank value. Although the coefficients of quadratic term are negative in columns 5 and 6, however, they are not significant. The linear term of value held by the largest shareholder enters positively and significantly at the 5% level (column 6) in Table 7, which suggests that the monitoring effects of large shareholders dominate the possible expropriation effects. The coefficient of the Percent of ownership held by the largest shareholder is not significant either (column 5 of Table 7)16. The insignificant coefficient on the Percent of ownership held by the largest shareholder is probably due to that shareholding in terms of dollar value rather than percentage of total shares is a better measure of block holders‘ incentive (Holderness, 2003).

The economic effects can be quite large. Using Model 5 in Table 6, the impact of one standard deviation increase in Ownership structure index equals 0.30, which is 16.76 percent of the mean value of MTBV of banks. If Ownership structure index increases from the minimum to maximum, bank value would increase 1.78, accounting for 99.3 percent of the mean value of MTBV.

4.2.3 Executive compensation index

Executive compensation index is positively and significantly related to bank valuation at the 5% or 10% levels in Table 6 (columns 3, 5, 9, and 11), indicating that use of incentive compensation boosts bank valuation. The use of option scheme and use of The regression results of MTBV on the percent of ownership and logarithm of value held by the five largest shareholders are similar with that held by the largest shareholder. We have not report the results. 16

share-based bonus to bank executives all impact bank valuation positively and significantly in Table 7 (column 7 and 8)17. Our regression results are consistent with Mehran (1995), which demonstrates that share-based compensation enhances firm value. The regulatory environments and other industry specific conditions may cause the pay-performance linkage in the banking industry to differ from that of industrial firms. Houston and James (1992) compare banks with non-bank firms. They find that banks are less reliant on managerial stock options than non-bank firms. Crowford et al. (1995) show that after deregulation, the pay-performance sensitivity of CEO compensation packages has increased significantly in US banks. Our results complement them by showing that incentive compensation, such as managerial stock options, enhances valuation of banks around the world.

The estimates in Table 8 imply that one standard deviation increase of Executive compensation index will lead to a 7.82 percent increase of MTBV of bank equity. If the Executive compensation index increases from minimal to maximal, the MTBV of bank equity will be increased by 23.67 percent.

4.2.4 Transparency index

As expected, the coefficients of Transparency index are positive and significant at the 5% or 10% levels in Table 6 (columns 4, 5, 10, and 11), indicating that higher level of transparency and disclosure improves corporate governance of banks. The results are consistent with the cross-country study by Klapper and Love (2004), which shows a positive relation between firm valuation and their S&P transparency rankings. Appointing one of the Big 4 accounting firms as auditors is positively related to MTBV at the 1% level in Table 7 (column 9). However, the coefficients of Cross listing in US and Disclose of executive compensation and shareholding are not significant. The insignificance of Cross listing in US is probably due to the relatively smaller sample size, as suggested by Dahya et al. (2008), which show a positive but insignificant relation between firm valuation and Cross listing in US. The insignificance of Disclose of executive compensation and shareholding may be due to that this variable is not representative of the level of transparency.

A one standard deviation increase in Transparency index will lead to a 7.62 percent increase of MTBV of bank equity. If the Transparency index increases from minimal to maximal, the MTBV of bank equity will be increased by 29 percent.

4.2.5 Corporate governance score

The CG score is constructed from Board structure index, Ownership structure index, Executive compensation index, and Transparency index. The relationship between CG score and bank valuation is positive and significant at 1% level, which is presented in Table 6 (column 6 and 12). The results show that the shareholders are willing to pay a In unreported regressions, we examine the relation between MTBV and Option schemes to non-executive directors and Variable compensation, the results are similar with that of Option schemes to top executives and Share-based bonus. 17

premium for banks with higher quality of overall corporate governance. Our results are consistent with Durnev and Kim (2005), who use Credit Lyonnais Securities Asia (CLSA) corporate governance score as proxy for quality of corporate governance in non-financial firms. Our results provide the first cross-country evidence on valuation and corporate governance in banking industry that comprehensively consider four internal governance mechanisms (board structure, ownership structure, executive compensation, and transparency).

The economic effect of CG score is large. Using Model 6 in Table 6, we get that one standard deviation increase of CG score will lead to a 21.07 percent increase of MTBV of bank equity. If the CG score increases from minimal to maximal, the MTBV of bank equity will be increased by more than 100 percent.

5 Corporate governance and bank valuation: extensions and robustness

5.1 Corporate governance, regulation and bank valuation

We have demonstrated that the corporate governance mechanisms, such as board independence, ownership concentration, executive compensation, and transparency that work in non-financial firms also work in banks around the world. However, it is incomplete to evaluate the impacts of governance without considering the roles of bank regulations. For one thing, the widespread official regulations may influence market valuation of banks directly. As argued by Caprio and Levine (2002), official bank regulations may arise in part to stop bank insiders from expropriating or misallocating bank resources. Thus, effective regulations may boost market valuation. More likely, regulations may arise to reduce excessive risk-taking by bank owners and reduce system risk. In this context, regulations could actually reduce bank valuation by forcing bank risk below what shareholders want. For the other thing, bank regulations may impact bank valuation indirectly through the effects of corporate governance mechanisms. Li and Song (2009) show that official regulation policies change bank-level internal governance structure. Laeven and Levine (2009) demonstrate that official regulations interact with ownership structure in shaping bank‘s risk-taking.

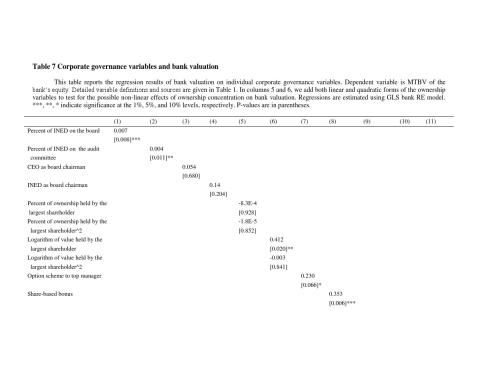

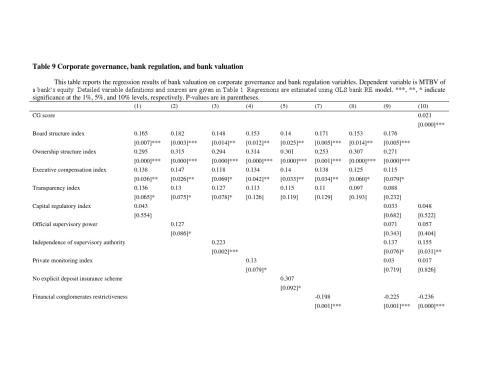

We therefore include the regulation variables in our regressions. We first include the regulation variables by adding them directly. The results are presented in Table 9. Then, we examine an alternative specification that allows regulations to exert indirect impact on bank valuation through interaction with corporate governance. The results are presented in Table 1018. We use the decile ranking of all the variables for regressions in Table 10. Using decile ranking of variables can alleviate the influences of extraordinary observations on regression results. Moreover, since the correlation coefficients between the interaction terms and CG score, and the correlation coefficients between the interaction terms and corresponding regulation variables are high, there is multicollinearity problem when we include CG score, regulation variables and the interaction terms simultaneously. To certain extent, using decile ranking of variables can mitigate the multicollinearity problem. 18

[Table 9 and 10 here]

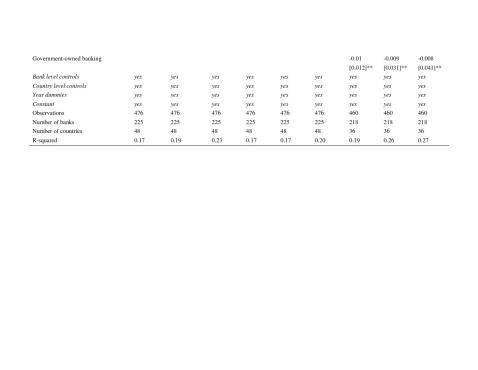

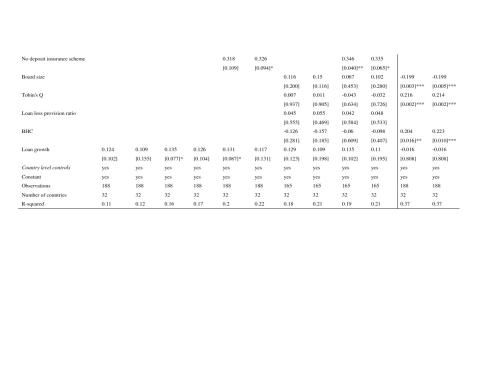

The results in Table 9 and Table 10 show that the effects of corporate governance mechanisms on bank valuation still hold when we control for possible influences of official regulations. Table 9 shows that some of the regulation policies do impact bank valuation. Official supervisory power, the Independence of supervisory authority, Private monitoring, and No deposit insurance scheme are positively and significantly related to bank valuation, however, Financial conglomerates restrictiveness and Government-owned banking are negatively related to bank valuation. The positive effect of Independence of supervisory authority is consistent with previous studies (Barth et al., 2003; Barth et al., 2004). Barth et al. (2003) suggest that independence for supervisory authorities is crucial for well-functioning banks, and more generally, for financial system stability. Barth et al. (2004) provide empirical evidence that Independence of supervisory authority is positively related to bank development. As discussed before, high restrictions on financial conglomerates may reduce bank franchise value and are related to low bank valuation. The negative effect of Government-owned banking is consistent with Barth et al. (2004) and La Porta et al. (2002), which supports the ―political‖ theory whereas challenges ―development‖ theory of government ownership (Shleifer and Vishny, 1998)19.

Laeven and Levine (2009) show that capital requirement regulation interacts with ownership structure to shape cross-country bank risk-taking. Li and Song (2009) show that powerful official supervision substitutes internal governance of banks, while promoting private monitoring enhances internal governance of banks. Capital requirement regulation, official supervisory power, and promoting private monitoring reflect the thoughts of the three pillars of The New Basel Accord (Basel II)20. We therefore include the interaction terms of bank-level CG score with country-level Capital regulatory index, Official supervisory power, and Private monitoring index respectively to test whether the three regulation variables impact the role of corporate governance on bank valuation. The results presented in Table 10 show that neither the interaction of Capital regulatory index with CG score, nor that of Official supervisory power with CG score is significant (columns 1 and 2 in Table 10). However, the interaction of Private monitoring index with CG score is positive and significant at 5% level. Moreover, the direct effect of CG score on bank The ―development‖ theory focuses on the necessity of financial development for economic growth, which is part of a broader sentiment in development economics that advocates government ownership of firms in the strategic economic sectors. The ―political‖ theory emphasizes political rather than social objectives, which suggests that politicians acquire control of banks in order to provide subsidies, employment, and other benefits to supporters, who return the benefits in the form of votes, political contributions, and bribes. 20 Basel II sets up a bank regulation and supervision framework. The influential ―best practice‖ recommendations of Basel II are based on three pillars. The first pillar deals with improved minimum bank capital requirements. The second pillar recommends regulations that empower official supervisory agencies to monitor and discipline banks. The third pillar focuses on envisioning greater market discipline and private monitoring through increased information disclosure by banks. 19

valuation is dominated by the effects of the interaction term21, which results in the insignificant coefficient of CG score in column 3 of Table 10. Together with the positive and significant coefficient on Private monitoring index in column 4 of Table 9, these results suggest that promoting private monitoring of banks enhances bank valuation moderately, and promoting private monitoring of banks complements with internal governance mechanisms in enhancing bank valuation. The results support the finding of Li and Song (2009) that promoting private monitoring enhances internal governance of banks. Previous studies show that firm-level corporate governance arrangements matter more for countries with weaker legal environment (e.g., Caprio et al., 2007; Dahya et al., 2008). We also look at the interaction of bank-level CG score with country-level investor protection to check whether our study is consistent with previous literature. The quality of Legal protection afforded to shareholders is often viewed as being made up of the statutory provisions (i.e., de jure protection) and the degree to which the statutes are enforced (i.e., de facto protection). Following Dahya et al. (2008), we use the product of Antidirector rights22 and Rule of law23 as proxy for the quality of legal environment. Consistent with previous studies, the coefficient on Legal protection is positive and significant at 5% level, and the coefficient on the interaction term is negative; however, the interaction term is not significant (Column 4 of Table 10). Although not significant, the negative coefficient on the interaction term is consistent with the view that bank-level corporate governance arrangements matter more for countries with weaker legal protection.

5.2 Endogeneity

We have assumed that corporate governance mechanisms of banks are exogenous. Nevertheless, as shown by Hermalin and Weisbach (2003) and Li and Song (2009), board of directors is an endogenous institution depending on firms‘ characteristics and regulatory environments. According to Demsetz and Lehn (1985), ownership structure is also 21 The equation

MTBV=?+?1*CG score+?2*(CG score*Private monitoring index)+?3*Private monitoring index+...+? can be

reshaped into MTBV=?+(?1+?2*Private monitoring index)*CG score+?3*Private monitoring index+...+?.

The total effects of CG score on bank valuation is measured by ?1+?2*Private monitoring index.

22 Antidirector rights index comes from La Porta et al. (1998). It is an index aggregating shareholder rights. The index is formed by adding 1 when: (1) the country allows shareholders to mail their proxy vote to the firm; (2) shareholders are not required to deposit their shares prior to the General Shareholders‘ Meeting; (3) cumulative voting or proportional representation of minorities in the board of directors is allowed; (4) an oppressed minorities mechanism is in place;

(5) the minimum percentage of share capital that entitles a shareholder to call for an Extraordinary Shareholders‘ Meeting is less than or equal to 10 percent of the sample median; or (6) shareholders have preemptive rights that can only be waived by a shareholders‘ vote. The index ranges from 0 to 6. 23 Rule of law index comes from International Country Risk Guide. It is an assessment of the law and order tradition in the country produced by the country-risk rating agency Political Risk Services. The index ranges from 0 to 6. Lower scores indicate less tradition for law and order.

endogenous. In fact, endogeneity is a significant concern in empirical research on corporate governance mechanisms. We address the potential concerns about the endogeneity of corporate governance by using both bank-level and country-level instrumental variables. The regression results using instrumental variables are presented in Table 11.

[Table 11 here]

First, we use bank-level instrumental variables for each of the CG score, Board independence index, Ownership structure index, Executive compensation index, and Transparency index respectively. It is difficult to construct instruments which both explain a bank‘s corporate governance mechanisms and are not affected by innovations in bank valuation. In column 1 of Table 11, for each bank, and for each of the CG score and the corporate governance indices, we use the average value of the variable of other banks in the country as an instrument for its CG score or corporate governance index24. We exclude countries with only one bank from the five instrumental variable regressions. The set of instruments capture the industry and country effects on a bank‘s corporate governance. The idea behind this set of instruments is that innovations in the valuation of one bank are unlikely to affect the corporate governance of other banks.

We also use country-level instrumental variables. As argued by La Porta et al. (2000), legal approach is a fruitful way to understand corporate governance and its reform. Legal origin can be considered as ―exogenous‖ because it was imposed by colonial power in many countries (Acemoglu and Johnson, 2005). Moreover, the legal origin itself is unlikely to impact bank valuation directly. Instead, it may exert an indirect impact through the channels of various institutions. Thus, in column 2, we use a dummy variable of whether the country is a common law country25 from La Porta et al. (2002) as instrument. In column 3, we use the percentage of years that a country has been independent since 1776 as an instrumental variable because ―countries that gained their independence in the 18th or 19th centuries had more opportunity to modify colonial institutions and adopt policies more conducive to broad-based economic growth‖ (Easterly and Levine, 1997). Li and Song (2009) find evidence that national regulation policies impact corporate governance of banks. Literature on deposit insurance suggests that more generous deposit insurance regimes reduce monitoring and market discipline from debt holders (e.g., Billett et al., 1998), and increase demand for internal governance mechanisms (Li and Song, For Columns 1-4 of Table 11, Panel A-E present the instrumental variable regression results for CG score, Board independence index, Ownership structure index, Executive compensation index and Transparency index respectively. For example, Column 1 presents results of five regressions. Panel A of Column 1 gives the result of instrumental variable regression for CG score, and we use the average value of the CG score of the other banks in the country as an instrument. Similarly, Panel B, C, D, and E of Column 1 present the results of instrumental variable regressions for Board independence index, Ownership structure index, Executive compensation index and Transparency index respectively. 25 Legal origin takes a value of one if the origin of the country‘s legal system is English (common law), and zero otherwise (civil law). 24

2009). Therefore, in column 4, we use the no explicit deposit insurance dummy26 and the mitigating moral hazard index27 as instruments. At last, in columns 5 and 6, we use instruments for all of the Board independence index, Ownership structure index, Executive compensation index, and Transparency index simultaneously. The instruments included are the legal origin dummy, a country‘s absolute value of latitude, ethnic fractionalization and the percentage of years that the country has been independent since 1776. The ―endowment theory‖ focuses on the roles of geography and the disease environment in shaping the institutional development (Acemoglu et al., 2001; Beck et al., 2003). Beck et al. (2003) find strong evidence that geographical endowment has substantial impacts on the development of long-lasting institutions. We therefore include a country‘s absolute value of latitude28 as instrumental variable. We also include ethnic fractionalization29 because it has been found that more ethnically diverse economies tend to choose institutions that allow those in power to expropriate benefits of others (Easterly and Levine, 1997).

The instrumental variables results are based on the Baltagi‘s (1981) two-stage least square random-effects estimator. In our first-stage regressions, all the instrumental variables enter jointly significantly at the 1% level, and we reject the F-test that the exogenous variables do not explain CG score and corporate governance indices at the 1% level. Regressions in columns 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6 are exactly identified, i.e., the number of excluded exogenous variables is equal to the number of endogenous regressors, and therefore we cannot do tests of overidentifying restrictions (OIR-test). We perform tests of overidentifying restrictions for regressions in column 4, and the Sargan-Hansen statistics do not reject the null hypotheses that instruments are uncorrelated to the residual. The coefficients of CG score are positive and statistically significant in all model specifications. Except for Ownership structure index, the coefficients of corporate governance indices are generally positive and significant. The results suggest that there is endogeneity problem for the ownership structure. However, the coefficients on Ownership structure index are still positive and significant when we use instruments for all the corporate governance indices simultaneously. Overall, results in Table 11 support our findings that higher level of corporate governance boost bank valuations. No explicit deposit insurance dummy comes from the Bank regulation and supervision database by Barth et al. (2006). It measures whether there is an explicit deposit insurance scheme and, if not, whether depositors were fully compensated the last time a bank failed. Lower value means a more generous deposit insurance regime.

27 Mitigating moral hazard index comes from the Bank regulation and supervision database by Barth et al. (2006). It measures the degree to which the actions taken to mitigate the moral hazard resulting from the deposit insurance scheme. It includes information on whether the deposit insurance funds are funded by the banks, whether the deposit insurance fees charged to banks vary based on some assessment of risk, and whether depositors are insured only for some percentage of their deposits. Higher value means greater mitigating of moral hazard problem.

28 The absolute value of the latitude of the country is from La Porta et al. (1999), which is scaled to take a value between zero and one. 29 Probability that two randomly selected individuals in a country will not speak the same language, which is from Easterly and Levine (1997). 26

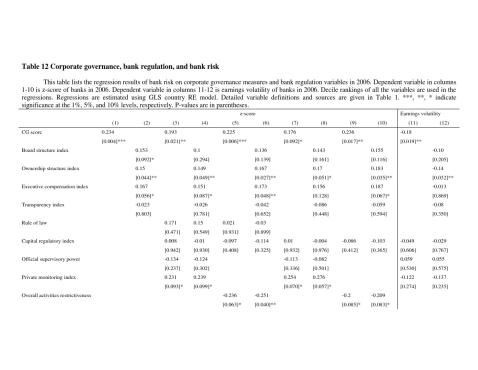

6 Corporate governance and bank risk

We have demonstrated that internal governance mechanisms enhance bank valuation, and the effects hold even when we control for the role of official regulations. Given the ongoing financial turmoil, it is valuable to examine how internal governance mechanisms influence bank risk-taking.