英语专业毕业论文文献综述格式

题目:

■■□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□□。

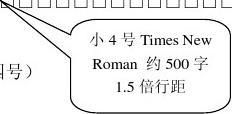

空2行(Times New Roman空1行 本部分参考文献的写法请参考《规范的参考文献格式》,字号为五号。文献间行距为1.5倍。

注:

本页页面设置为上下2.5厘米,左3右2厘米

文献综述的写法及格式

文献综述是对某一方面的专题搜集大量情报资料后经综合分析而写成的一种学术论文,它是科学文献的一种。文献综述是反映当前某一领域中某分支学科或重要专题的最新进展、学术见解和建议的它往往能反映出有关问题的新动态、新趋势、新水平、新原理和新技术等等。

文献综述与“读书报告”、“文献复习”、“研究进展”等有相似的地方,它们都是从某一方面的专题研究论文或报告中归纳出来的。但是,文献综述既不象“读书报告”、

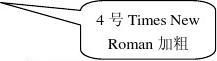

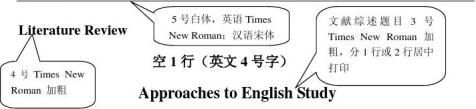

题目:Approaches to English Study 姓名:齐莉杰 学号:06 班级:2001级2班

“文献复习”那样,单纯把一级文献客观地归纳报告,也不象“研究进展”那样只讲科学进程,其特点是“综”,“综”是要求对文献资料进行综合分析、归纳整理,使材料更精练明确、更有逻辑层次;“述”就是要求对综合整理后的文献进行比较专门的、全面的、深入的、系统的论述。总之,文献综述是作者对某一方面问题的历史背景、前人工作、争论焦点、研究现状和发展前景等内容进行评论的科学性论文。

一、格式与写法

文献综述的格式与一般研究性论文的格式有所不同。这是因为研究性的论文注重研究的方法和结果,特别是阳性结果,而文献综述要求向读者介绍与主题有关的详细资料、动态、进展、展望以及对以上方面的评述。因此文献综述的格式相对多样,但总的来说,一般都包含以下四部分:即前言、主题、总结和参考文献。撰写文献综述时可按这四部分拟写提纲,再根据提纲进行撰写。

前言部分,主要是说明写作的目的,介绍有关的概念及定义以及综述的范围,扼要说明有关主题的现状或争论焦点,使读者对全文要叙述的问题有一个初步的轮廓。

主题部分,是综述的主体,其写法多样,没有固定的格式。可按年代顺序综述,也可按不同的问题进行综述,还可按不同的观点进行比较综述,不管用那一种格式综述,都要将所搜集到的文献资料归纳、整理及分析比较,阐明有关主题的历史背景、现状和发展方向,以及对这些问题的评述,主题部分应特别注意代表性强、具有科学性和创造性的文献引用和评述。

总结部分,与研究性论文的小结有些类似,将全文主题进行扼要总结,对所综述的主题有研究的作者,最好能提出自己的见解。

参考文献虽然放在文末,但却是文献综述的重要组成部分。因为它不仅表示对被引用文献作者的尊重及引用文献的依据,而且为读者深入探讨有关问题提供了文献查找线索。因此,应认真对待。参考文献的编排应条目清楚,查找方便,内容准确无误。

二、注意事项

由于文献综述的特点,致使它的写作既不同于“读书笔记”“读书报告”,也不同于一般的科研论文。因此,在撰写文献综述时应注意以下几个问题:

⒈搜集文献应尽量全。掌握全面、大量的文献资料是写好综述的前提,否则,随便搜集一点资料就动手撰写是不可能写出好多综述的,甚至写出的文章根本不成为综述。 ⒉注意引用文献的代表性、可靠性和科学性。在搜集到的文献中可能出现观点雷同,有的文献在可靠性及科学性方面存在着差异,因此在引用文献时应注意选用代表性、可靠性和科学性较好的文献。

⒊引用文献要忠实文献内容。由于文献综述有作者自己的评论分析,因此在撰写时应分清作者的观点和文献的内容,不能篡改文献的内容。

⒋参考文献不能省略。有的科研论文可以将参考文献省略,但文献综述绝对不能省略,而且应是文中引用过的,能反映主题全貌的并且是作者直接阅读过的文献资料。

总之,一篇好的文献综述,应有较完整的文献资料,有评论分析,并能准确地反映主题内容。

第二篇:英语专业毕业论文文献综述样例

英语专业毕业论文文献综述样例

参考范文1

Distance Learning

This paper will summarize two articles on distance learning and give the author?s views on the benefits and obstacles of implementing distance-learning in a junior and senior high school learning environment.

Jeannette McDonald, in her article: Is “As good as face-to-face” as good as it gets? (2002), raises a very important question as to whether “[the] goal [of online learning should be] to meet existing standards of traditional education” (McDonald, 2002) or “has distance learning, and especially online education opened the door to enhanced strategies in teaching and learning” (McDonald, 2002)? Online learning may just be “doing different things” (McDonald, 2002). What are these different things? Jeannette McDonald claims that “distance education can be a frontier for new methods of communication giving rise to innovative teaching and learning practices that may not be possible in traditional, place-bound education” (2002). The article discusses both the positive and “potential negative impacts of online education” (McDonald, 2002).

There are many benefits to using online distance learning environments. Online education is available “anyplace, anytime [for] global communities of learners based on shared interests” (McDonald, 2002). Jeannette McDonald claims that “online education [with its] group-based instruction [and] computer mediated communication (CMC) provides an opportunity for new development and understanding in teaching and learning” (2002). CMC encourages “collaborative learning [by not providing] cues regarding appearance, race, gender, education, or social status bestowing a sort of anonymity to participants” (McDonald, 2002). Distance also “permits the expression of emotion (both positive and negative) and promotes discussion that normally would be inhibited. [Yet, this same] text-based [positive aspect of online learning], makes online education more cumbersome and therefore takes more time than face-to-face learning. [In addition,] the sheer bulk of messages can be overwhelming” (McDonald, 2002). The learner only has the written text and no other “non-verbal” (McDonald, 2002) cues. This may confuse the learner and cause “misunderstanding” (McDonald, 2002). The article lists the “seven principles of good practice in undergraduate education” (McDonald, 2004) published in 1987 by the American Association of Higher Education Bulletin. Jeannette McDonald claims that “online education has the potential to achiever all of these practices” (2002). There is a need for quality and standards for distance learning. “In April 2000, the institute of Higher Education Policy produced a study with 24 benchmarks for the success in Internet-based distance education” (The Institute for Higher Education Policy, 2000).

Although Jeannette McDonald feels that there are “biases against distance learning programs” (2002), her recommendation is “to take advantage of the potential of online education

[by striving] to understand the technology and how it affects human communication and interaction” (2002).

“In the road to dotcom in education” (2004), Mark David Milliron deals with a very progressive idea that suggests educators “slow … down from [their] busy lives… to be free to focus first on connecting with learners and connecting them to learning … before [they] end up feeling like [they] are no longer using technology, but are being used by it” (Milliron, 2004). He compares education to a highway where educators are faced with many “road hazards”. Mark

Milliron claims that “looking for road hazards on a journey takes concentration [which] is not often practiced by those with a need for speed or those caught up in their competitive drives” (2004). He gives examples of how ridiculous people are becoming when they “strive to stay connected [to cell phones and e-mails at the price of] deep personal connections with [their] family members and friends” (Milliron, 2004). He quotes Dr. Edward Hallowell, who ironically states “how many electronic connections we have today, yet how hard it is for us to form authentic and deep personal connections” (Milliron, 2004). Mark Milliron gives an excellent comparison of how technology has blinded people when he says that they are becoming “more and more like Pavlov?s dogs: at the ding of incoming e-mails they stop what they?re doing, salivate, and rush to the screen” (2004). There is pressure to keep up with the times as well as “a cost-of-entry issue regarding technology in education. Without a certain level of technology services and learning options, many students will not consider attending [a certain] institution” (Milliron, 2004). Mark Milliron claims that “any technology has to prove that it will ultimately improve or expand learning” (2004). This will come about if educators “slow down, look around, and get on the road to DotCalm- a place [to] thoughtfully engage and explore all aspects of technology, good, bad, or indifferent; …a place with mindful focus on the people and passions that make life worth living” (Milliron, 2004).

The author of this paper has been trying to implement distance learning in both junior and high school environments for the past year. The school has added a platform called “Britannica” to make online learning possible in case of emergency or a teacher?s strike. The students are not willing to take the time to go in and look up homework assignments and other online learning activities. The author keeps reminding students to add their e-mail addresses to the form but they are unwilling to cooperate. The process is very slow with little results. Some teachers have made these online lessons compulsory for their students. ESL students shy away from online classes. They have expressed fear of having their work viewed by others. Every student has to login to the school site but within a classroom, everyone who takes the class can view the other?s work. ESL students don?t see the advantage of learning by sharing. Should online learning be an issue of control or should students be convinced of its value as an authentic learning tool? Fear and a threatening environment don?t enhance learning according to brain-based learning research. “How students ?feel? about a learning situation determines the amount of attention they devote to it”(Sousa, 1998). “Positive emotions ensure that learning will be retained” (Lackney, 2002). It?s very important to discuss with students how they feel about technology and online learning so that they feel good about what they are doing. The author feels that the process of implementing online distance learning is a slow and delicate one. Change will eventually come about but it will take time. As Mark Milliron has said “[let?s not let] new technology … get in the way of learning” (2004). Let?s calm down as we “focus first on connecting with learners [and only then begin] connecting them to learning” (Milliron, 2004).

参考范文2 Language and Gender

With the general growth of feminist work in many academic fields, it is hardly surprising that the relationship between language and gender has attracted considerable attention in recent years. In an attempt to go beyond “folk linguistic” assumptions about how men and women use language (the assumption that women are “talkative”, for example), studies have focused on anything from different syntactical, phonological or lexical uses of language to aspects of conversation analysis, such as topic nomination and control, interruptions and other interact ional

features. While some research has focused only on the description of differences, other work has sought to show how linguistic differences both reflect and reproduce social difference. Accordingly, Coates (1988) suggests that research on language and gender can be divided into studies that focus on dominance and those that focus on difference.

Much of the earlier work emphasized dominance. Lakoff?s (1975) pioneering work suggested that women?s speech typically displayed a range of features, such as tag questions, which marked it as inferior and weak. Thus, she argued that the type of subordinate speech learned by a young girl “will later be an excuse others use to keep her in a demeaning position, to refuse to treat her seriously as a human being” (1975, p.5). While there are clearly some problems with Lakoff?s work - her analysis was not based on empirical research, for example, and the automatic equation of subordinate with ?weak? is problematic-the emphasis on dominance has understandably remained at the centre of much of this work. Research has shown how men nominated topics more, interrupted more often, held the floor for longer, and so on (see, for example, Zimmerman and West, 1975). The chief focus of this approach, then, has been to show how patterns of interaction between men and women reflect the dominant position of men in society.

Some studies, however, have taken a different approach by looking not so much at power in mixed-sex interactions as at how same-sex groups produce certain types of interaction. In a typical study of this type, Maltz and Borker (1982) developed lists of what they described as men?s and women's features of language. They argued that these norms of interaction were acquired in same-sex groups rather than mixed-sex groups and that the issue is therefore one of (sub-)cultural miscommunication rather than social inequality. Much of this research has focused on comparisons between, for example, the competitive conversational style of men and the cooperative conversational style of women.

While some of the more popular work of this type, such as Tannen (1987), lacks a critical dimension, the emphasis on difference has nevertheless been valuable in fostering research into gender subgroup interactions and in emphasizing the need to see women?s language use not only as ?subordinate? but also as a significant sub-cultural domain.

Although Coates? (1988) distinction is clearly a useful one, it also seems evident that these two approaches are by no means mutually exclusive. While it is important on the one hand, therefore, not to operate with a simplistic version of power and to consider language and gender only in mixed-group dynamics, it is also important not to treat women?s linguistic behavior as if it existed outside social relations of power. As Cameron, McAlinden and O?Leary (1988) ask, “Can it be coincidence that men are aggressive and hierarchically-organized conversationalists, whereas women are expected to provide conversational support?” (p.80). Clearly, there is scope here for a great deal more research that is based on empirical data of men?s and women?s speech; operates with a complex understanding of power and gender relationships (so that women?s silence, for example, can be seen both as a site of oppression and as a site of possible resistance); looks specifically at the contexts of language use, rather than assuming broad gendered differences; involves more work by men on language and gender, since attempts to understand male uses of language in terms of difference have been few (thus running the danger of constructing men?s speech as the ?norm? and women?s speech as ?different?); aims not only to describe and explain but also to change language and social relationships.

-

文献综述格式及范文

文献综述格式一文献综述的引言包括撰写文献综述的原因意义文献的范围正文的标题及基本内容提要二文献综述的正文是文献综述的主要内容包括某…

-

文献综述格式范本

中国文化产品贸易现状及问题分析文献综述三号黑体居中姓名班级学号前言小标题四号宋体加粗文化经济是中国经济的重要组成部分同时又是推动整…

-

文献综述模板(超强整合)

文献综述模板(超强整合)文献综述(论文标题,小二号,黑体,居中)姓名摘要:内容??(“摘要:”两个字要求是黑体小四,顶格写;摘要的…

-

文献综述模板范文

海南大学毕业论文题目学号姓名年级学院系别专业指导教师完成日期文献综述报告芦荟提取物的杀虫活性初探20xx0124035张宇博20x…

-

文献综述规范及范文

贵州大学人民武装学院20xx届本科毕业生毕业论文设计文献综述撰写规范为了培养学生独立从事学术研究的能力特别是培养学生检索搜集整理综…

-

毕业论文的文献综述要怎么写

I什么是毕业论文文献综述?毕业论文文献综述,简单地说就是在参考一系列的参考文献后,对文献进行相关的整理融合,加入自己的想法和观点,…

-

毕业论文文献综述究竟该怎么写

毕业论文文献综述究竟该如何下手默认分类20xx-09-1900:05阅读3933评论0字号:大中小文献综述是对某一方面的专题搜集大…

-

毕业论文文献综述格式

政法与历史学院毕业论文“文献综述”的内容及格式要求一、内容要求文献综述是在研究选题确定后并在大量搜集、查阅相关文献的基础上,对相关…

-

本科毕业论文文献综述外文翻译规范

本科毕业论文(设计)文献综述和外文翻译撰写要求与格式规范(20xx年x月修订)一、毕业论文(设计)文献综述(一)毕业论文(设计)文…

-

毕业论文文献综述格式及写作技巧(附文献综述范文)

文献综述是在对文献进行阅读、选择、比较、分类、分析和综合的基础上,研究者用自己的语言对某一问题的研究状况进行综合叙述的情报研究成果…

-

综述报告格式

综述一、综述概述1.什么是综述:综述,又称文献综述,英文名为review。它是利用已发表的文献资料为原始素材撰写的论文。综述包括“…