关于健康饮食的调查报告

关于健康饮食的调查报告

组员:李远航(负责人)、孙园园、张惠中、张文静、桑琳琳、杜峰

健康饮食的背景:

调查结果:经过我们的调查,

在高中生中,有10%的学生经常不吃早餐,27%的学生有时不吃;15%的学生,三餐食量不合理。这些都是严重的饮食不健康现象

首先,不吃早餐是有极大危害的:

一、对大脑的危害。虽说脑组织的重量只占人体重的2-3%,但脑的血流量每分钟约为800毫升,耗氧量每分钟约为45毫升,耗糖量每小时约为5克。青少年的脑组织正处于发育期,血、氧、葡萄糖的需求量比成人还高。如血糖过低,脑意识活动就会出现障碍,长期如此,势必影响脑的重量和形态发育。

二、对消化系统的危害。正常情况下,头天晚上吃的食物经过六小左右就从胃里排空进入肠道。第二天若不好吃早餐,胃酸及胃内的各种消化酶就会去“消化”胃粘膜层。长此以往,细胞分泌粘液的正常功能就会遭到破坏,很容易造成胃溃疡及十二指溃疡等消化系统疾病。

三、造成动脉硬化且更易导致肥胖。有不少青少年学生是怕长胖而不吃早餐的。这种做法毫无科学道理。人体对热量的需求是有标准的,不吃早餐,势必加大中、晚餐的进食量。而晚餐后一般运动量较小,更容易造成脂肪积累而导致肥胖。另外,长期不吃早餐还会使胆固醇、脂蛋白沉积于血管内壁,导致血管硬化。

四:让你反应迟钝:早饭是大脑活动的能量之源,如果没有进食早餐,体内无法供应足够血糖以供消耗,便会感到倦怠、疲劳、脑力无法集中、精神不振、反应迟钝。

五:慢性病可能“上”身:不吃早餐,饥肠辘辘地开始一天的工作,身体为了取得动力,会动用甲状腺、副甲状腺、脑下垂体之类的腺体,去燃烧组织,除了造成腺体亢进之外,更会使得体质变酸,患上慢性病。

六:肠胃可能要“造反”:不吃早餐,直到中午才进食,胃长时间处于饥饿状态,会造成胃酸分泌过多,于是容易造成胃炎、胃溃疡。

七:便秘“出笼”:在三餐定时情况下,人体内会自然产生胃结肠反射现象,简单说就是促进排便;若不吃早餐成习惯,长期可能造成胃结肠反射作用失调,于是产生便秘。

八:会让你更靠近肥胖族:人体一旦意识到营养匮乏,首先消耗的是碳水化合物和蛋白质,最后消耗的才是脂肪,所以不要以为不吃早饭会有助于脂肪的消耗。相反,不吃早饭,还会使午饭和晚饭吃得更多,瘦身不成反而更胖。

营养学家们的证实,早餐是每个人一天中最不容易转变成脂肪的一餐。如果每天不吃早餐只会让午餐吃得更多。

所以早餐很重要

其次,早餐、午餐和晚餐的比例最好是3∶2∶1,这样子就能让你在一天内所吃的精华在体力最旺盛的时间内消耗掉。

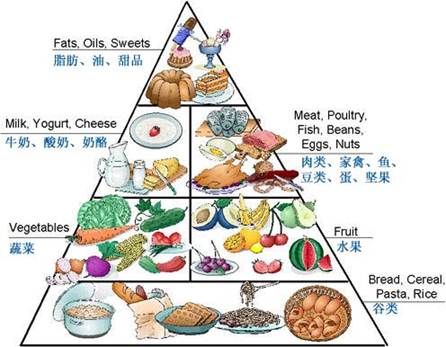

在饮食搭配上:

21%的人摄入脂肪、油、甜品过量;

20%的人摄入奶制品过量;

13%的人摄入高蛋白食品过量;

13%的人摄入高蛋白食品过量;

18%的人摄入蔬菜不足;

36%的人摄入水果不足;

22%的人摄入谷类不足;

有11%的人饮食中营养不够丰富;

而只有12%的人勉强符合健康的膳食宝塔。

综上所述,高中生的饮食状况不容乐观

除了对他们的饮食行为进行调查,我们还细致的调查了他们的饮食意识:

只有约1∕5的人有强烈的健康饮食观念;

而超过1∕2的人不够重视;

总体来看,学生的健康饮食观念较为淡薄

第二篇:基线调查报告:小学推行健康饮食基线研究调查摘要P20xx09150165_0166_19xx2

@ 香港特區政府衞生署

二零零六年九月

香港特區政府衞生署衞生防護中心 中央健康教育組編製

如有需要,請聯絡衞生署中央健康教育組,地址:香港灣仔軒尼詩道130號修頓中心七樓 本報告書亦可在衞生署中央健康教育組網頁下載,網址http://www.cheu.gov.hk。

@ Department of Health

Copyright September 2006

Produced and published by

Central Health Education Unit, Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health, Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, 7/F, Southorn Centre, 130 Hennessy Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong.

Copies of this publication are available from the Central Health Education Unit and from the website http://www.cheu.gov.hk.

目錄

背景及目的

研究方法

主要調查結果

參與者背景資料 學生對其飲食習慣的觀感 學生對健康飲食的認識 學生選擇食物的態度 學生的飲食習慣 家長對其子女飲食習慣的觀感 選擇食物的考慮 選擇午膳供應商的考慮 推廣健康飲食習慣的措施 學校的飲食環境 影響學生飲食習慣的因素

建議

總結

1 2 3 3 3 3 4 4 5 5 6 6 6 7 8 12

Content

Background & Objectives

Research Methodology

Key Findings of the Study

Demographics Students’ perception of their own eating habit Knowledge on healthy eating Attitude on food preference Students’ eating practice Parents’ perception of their child’s eating habit Consideration in choosing food Consideration in choosing lunch caterer Measures to promote healthy eating habit Schools’ eating environment Factors contributing to students’ eating practice

Recommendations

Conclusion

13 14 15 15 15 15 16 16 17 18 18 18 18 19 21 25

背景及目的

___________________________________________________________________________________

衞生署的資料顯示,小學學童的肥胖比?有上升趨勢,由一九九七/九八年度的16.4%增至二零零四/零五年度的18.7%。換言之,幾乎每五名學童?有一名屬於肥胖。有見及此,預防學童肥胖的措施應予推行。

向在學兒童推廣健康飲食,是二零零五至二零零六年度施政報告開列的目標之一。為籌備即將在全港推行的「健康飲食在校園」運動,衞生署於二零零六年第一季進行了小學推行健康飲食基線研究,研究結果將作發展相關的健康推廣資源及日後檢討運動成效之參考。

研究目的如下:

? 調查現時小學生對於健康飲食的認識、態度和行為,以及家長對校園健康飲食的態

度;

? 探索小學校園的食物營養環境,例如午餐盒、小食部及售賣機提供的食品種類,以及

學校推行的飲食政策;

? 找出影響小學生飲食習慣及於小學校園推廣健康飲食的因素;

? 就「健康飲食在校園」運動的策略及資源發展提出建議。

1

研究方法

___________________________________________________________________________________

調查是以分層群組抽樣方式,以學校數目和類別為基礎,按比例從各區抽出來自44間小學的小四及小五學生、其家長,以及校長/學校代表參與調查。

衞生署分別就學生、家長及校長/學校代表設計了三套不同的自填問卷。問卷在二零零六年一月經過測試,最後版本用於同年二月十三日至三月六日期間進行的正式調查。

調查發出學生及家長問卷共9,831套,收回的學生及家長問卷數目分別為9,222及9,014份,回應?分別為93.8%及91.7%。學校問卷方面,全部44間獲抽中參與的學校均有回覆,回應?達100%。

2

主要調查結果

___________________________________________________________________________________

參與者背景統計數據

受訪學生的班級和性別分布與全港小四及小五學生的整體數據相近,小四學生佔48.5%,女生則佔47.9%。

大部分受訪的學生家長為女性(77.2%),約六成具中學教育程度,另有約四分之一(24.6%)達大學或以上教育程度。其中六成家長的家庭總收入少於港幣20,000元。

就種類而言,抽取的學校樣本與全港的小學呈現輕微差異。大部分受訪學校為全日制小學(93.2%)和男女校(97.7%);48%為天主教或基督教學校;45.5%沒有宗教背景。

學生對其飲食習慣的觀感

研究結果顯示,大部分學生認為他們的飲食習慣屬非常健康、健康或可接受(89.4%),只有3.6%認為他們的飲食習慣屬不健康或非常不健康。

學生對健康飲食的認識

在調查中,學生被要求在六組食物或飲品的配搭中選出較健康的組別,並正確地排列「健康飲食金字塔」內的食物。他們一般對於健康飲食都有良好的認識,「知識指數」(Knowledge Index)帄均為8.1(最高值為10)。

小組分析顯示,女生的帄均知識指數比男生顯著高出0.5(8.4,相對於7.9,p<0.0001)。

3

學生選擇食物的態度

學生選擇食物的「態度指數」(Attitude Index)顯示,他們普遍較不喜愛健康食物。他們的態度指數帄均只有2.6(最高值為6),當中有18.9%學生的態度指數為零。值得注意的是,在六組食物及飲品當中,較多學生偏愛漢堡飽加炸薯條、乾炒牛河、雪糕及熱狗等不健康的食物。

小組分析顯示,女生及認為自己有健康飲食習慣的學生(兩者的帄均態度指數均為2.8)比男生及認為自己飲食習慣不健康的學生(帄均態度指數分別為2.39及1.84)有較佳的選擇食物態度(p<0.0001)。此外,知識指數較高的學生,態度指數亦較高(p<0.0001)。

學生的飲食習慣

是項以學生有否吃早餐及各種食物的每天進食次數來評估他們的飲食習慣。

大部分學生(85.7%)在調查當天都有吃早餐。至於各種食物的每天攝取量,大部分學生(70.7%至93%)的奶類、蔬菜、五穀類、肉、魚、蛋及豆類進食次數均屬適當。然而,只有約半數學生有吃水果的健康習慣(56.7%的學生每天吃兩次或以上)。此外,只有8.7%至24.7%的學生沒有進食不健康的食物,例如含有添加糖分的飲品、煎炸食物、高糖分、高脂肪及高鹽分的食物。

與態度指數相若,學生的「行為指數」(Practice Index)偏低,帄均只得5.3(最高值為

11)。小組分析顯示,下列組別的行為指數顯著較其對應組別為高:(1)女生(5.47,相對男生的5.22,p<0.0001);(2)由家長決定家中飲食的學生(5.40,相對由學生決定的5.01,p<0.0001);(3)認為自己飲食習慣健康的學生(5.44,相對不健康的4.30,p<0.0001);(4)就讀全日制學校的學生(5.36,相對半日制學生的4.89,p<0.0001)。調查發現,學生的行為指數與態度指數及知識指數有顯著關係(p≤0.0001)。

4

家長對其子女飲食習慣的觀感

大部分家長表示他們的子女有每天吃早餐的習慣(72.9%),這與學生自我報告的情況吻合。大部分家長(82.6%至97.6%)亦表示他們的子女有每天在家中進食最少一次五穀類、肉、魚、蛋、豆類、蔬菜及水果類食物的健康習慣。較少家長(64.8%)表示知道子女有攝取奶類食物。另一方面,只有5.5%至6.9%的家長表示他們的子女從來沒有吃高糖分、煎炸食物及含有添加糖分的飲品;此外,分別有10%及20.6%的家長表示其子女從來沒有吃高脂肪及高鹽分的食物。

在設有小食部的學校當中,少於四成家長知道其子女在該處購買過何種食物及飲品。家長亦被問及其子女會否帶小食回校進食,過半數(61.6%)表示其子女有此習慣,而最普遍帶回校進食的小食為餅乾(69%)及糖果(33.8%)。

相對於學生的自我評估,只有過半家長(58.3%)認為其子女有健康的飲食習慣。值得注意的是,26.4%的家長不知道其子女的飲食是否健康。

近四成家長(39.3%)表示不容易養成健康飲食習慣,普遍原因為『沒有時間預備健康食物』(28.4%)、『健康食物味道不佳』(25.7%)及『健康食物缺乏變化』(17.1%)。

選擇食物的考慮

清潔及衞生程度(81.9%)是學生選擇食物的首要考慮因素,其次是味道(67.1%)、新鮮程度(63.8%)、營養價值(62.1%)及價格(53.5%)。

家長認為清潔及衞生程度(81.5%)是選擇食物的主要考慮因素,其次是營養價值(77.5%)、新鮮程度(70.9%)及孩子的喜好和口味(64.6%);此外,味道(41.9%)和價格(39.6%)亦是為孩子選擇食物的考慮因素。

5

選擇午膳供應商的考慮

食物是否營養豐富及有益健康,是學校代表選擇午膳供應商的最重要考慮因素,共得1,313分;其次是食物安全事故記錄(610分)、公司規模(525分)、食品價格(519分)及食物味道和學生喜好(492分)。

推廣健康飲食習慣的措施

就推廣健康飲食習慣的措施而言,家長及學校代表雙方均非常贊成向學生提供健康教育(支持?分別為59.8%及84.1%)。在校內推行健康飲食政策的提議亦廣為家長及學校代表支持(分別為51.1%及51.3%)。

學校的飲食環境

近62%及48%的小學分別有推行健康午膳或健康小食政策。然而,仍有約三成小學(27.3%)並未制訂任何健康飲食政策。

大部分學校為學生向供應商訂購午餐盒(81.4%)或安排午膳供應商到校供膳(17.3%),午膳供應商(82.9%)及老師(77.2%)是學校午膳餐單的主要決策者。大部分小學均設有飲水機(83.1%),有一半的學校設有小食部(53.9%)或售賣機(56.5%)。多數的售賣機供應含有添加糖分的紙包或樽裝飲品(95.3%)、鮮奶和荳奶等飲料及製成品(75.7%),以及蒸餾水/礦泉水(63%)。

研究結果亦顯示,大部分小學都沒有向小食部或售賣機的營運商提出售賣食物或飲品種類的規定。學校的「規條指數」(Regulation Index)極低,帄均只有3(最高值為10)。在有制訂規定的學校當中,約有一半或少於一半要求小食部售賣健康食物,包括果汁或果乾(52%)、新鮮水果(45%)及蔬菜(36%),而52%則對售賣機出售含有添加糖分的飲品有所限制。同樣地,只有少於一半的受訪學校(42.7%)規定午餐盒每天所提供的蔬菜分量。相反地,大多數的家長均要求規定午膳提供主要食物類別的分量 (85% 至90%),當中包括水果和蔬菜,並且強制要求小食部售賣水果 (63%) 和蔬菜 (56%)。

6

影響學生飲食習慣的因素

線性回歸(linear regression)顯示,學生飲食習慣主要與(1)學生認為自己的飲食習慣屬健康(系數為0.74,p<0.0001);(2)家長認為其子女的飲食習慣屬健康(系數為0.34,p<0.0001);(3)由家中安排午膳的學生(系數為0.34,p-<0.0001);(4)限制小食部售賣含有添加糖分的飲品(系數為-0.25,p <0.0001);(5)學生選擇食物的態度(系數為0.22,p<0.0001)有關係。

學生飲食習慣的變化,當中合共約十分之一(11.5%)是與這些因素有關。在闡釋結果時應多加留意,有其他影響學生飲食習慣的因素未有包括於是項調查之內,例如家庭因素、產品行銷、食物供應及大眾傳媒影響。此外,行為指數是透過受訪學生進食各種食物次數計算出來,當中有關的題目並未經認證,而健康及不健康的分界亦僅為最佳估計。

7

建議

___________________________________________________________________________________

根據研究結果作出的建議:

1. 調查結果顯示,家長及學校代表均贊成向學生推行健康教育(59.8%及84.1%)及在校

內推行健康飲食政策(51.1%及51.3%)。此外,近四成受訪學校支持加強對家長的教育及家校合作。這充分支持了「健康飲食在校園」運動應以學生、家長及校園營養環境為影響對象的理念。事實上,外地經驗顯示從多方面入手能更有效地在校園推廣健康飲食。

2. 結果顯示,學生對健康飲食的認識和態度有着明顯的差距。學生普遍對於健康飲食有

良好的認識(帄均知識指數為8.1(最高值為10)),但他們在健康飲食方面的態度及行為均屬一般(帄均態度指數為2.6(最高值為6),帄均行為指數為5.3(最高值為

11))。大部分學生認為自己的飲食習慣至少是可以接受(89%),與相對較低的帄均行為指數相反。因此,以學生為對象的營養教育計劃應更着力於塑造學生對健康飲食的正面態度及培養健康飲食的習慣。舉例說,具創意的網上遊戲及如烹飪比賽等的體驗式學習,能幫助學生在樂趣中將知識付諸實踐。此外,為減輕教師的工作量,可考慮發展適用於課堂或課外活動的教學資源。

8

3. 大部分(83%)受訪的家長擔當決定家中食物決策者的角色。為人父母者可為子女樹立

榜樣,因為他們是教育子女選擇健康食物的關鍵人物。雖然家長可以為學生預備午餐盒及小食,但他們對在學校所提供的食物影響力相對較低。約九成學校設有工作小組,監督學生膳食服務,但當中只有七成有家長代表的參與。此外,大部分家長不知道學校小食部及售賣機提供予學生的食物及飲品種類,而這些食品往往屬高能量及添加糖分等不健康的種類。因此,家長應更積極參與及聯同校方推廣校園健康飲食,例如:可鼓勵家長參與制訂健康飲食政策,參與膳食服務工作小組,選擇膳食供應商並監察其服務表現,或於午膳及小息時間到學校當義工。另外,透過宣傳活動及教育資料,亦可為家長提供預備午餐盒及小食的實務資訊。

4. 現時只有六成學校制訂了健康午膳政策,而半數的學校並沒有向午膳供應商訂明任何

要求。因此,自攜午膳或由家長攜送午膳到學校的學生有較健康的飲食習慣,這情況不足為奇。故此,學校有需要制訂健康午膳政策。就此而言,衞生署編製的《小學午膳營養指引》應向學校廣為推介,以?校方將指引納入與午膳供應商訂立的合約內,並給使用者(學生、家長及學校)作為監察供應商服務表現的參考資料。

5. 學校及家長均認為營養價值是選擇食物的主要考慮因素。然而,學生卻認為食物的清

潔及衞生、味道及新鮮程度較為重要。在覺得健康飲食不容易養成的家長當中,26%認為健康食物味道不佳。因此,食物供應商在注意食物的營養價值之餘,亦要兼顧衞生和味道。學校/家長與食物供應商的雙互溝通,加上家長/學生的支持,是改變舊有觀念,令人認識到健康食物亦可既美味又吸引的關鍵因素。

9

6. 本研究發現,逾半學校設有小食部(53.9%)或售賣機(56.5%)。學生在小食部或售賣

機購買他們喜愛或偏好的食物代替午餐或作為小食的情況並非罕見。如前述,小食部和售賣機出售很多不健康的食物。有那麽多不健康的食品可供選擇,學生揀選吃不健康小食的機會也會提高。而衞生署於二零零四年進行的一項定質研究亦顯示,學校甚少有健康食物供應。為使學生較容易選擇健康食物,衞生署的《小學小食營養指引》應廣為傳達至各學校,以供校方制定健康小食政策及與小食部和售賣機營運商訂立合約時作為參考。

7. 學校應就食物供應事宜與午膳供應商、小食部及售賣機營運商聯絡,清楚列明各項有

關食物的要求及限制。令午膳供應商、小食部及售賣機營運商瞭解他們在維持學生健康方面擔當着重要的角色。營運商對既定規條的遵行及定期的檢討,都是達成小學生養成健康飲食習慣最重要的因素。

8. 衞生署於過往幾年進行的市場調查均一致顯示,透過大眾傳媒──尤其是電視──推

出的廣告仍是市民接收健康資訊的最主要渠道。根據衞生署推行「日日二加三」運動(即每天進食兩份水果及三份蔬菜以保持均衡飲食)的經驗,署方可繼續以推行運動來吸引學生及家長注意多吃健康的食物,並對不健康的說「不」。多項研究顯示,透過大眾傳媒(包括電視、電台、報紙及廣告),能有效將訊息傳遞予目標社群,引起他們注意,並改變他們的態度。

9. 為了匯集健康飲食資訊以供各界人士參考,建議成立主題網站,如美國農業部食物及

營養處(Food and Nutrition Service, Department of Agriculture)統籌的「Eat Smart, Play Hard」網站(http://www.fns.usda.gov/eatsmartplayhard/)或前述的衞生署「日日二加三」運動(http://2plus3.cheu.gov.hk/)網站,以方?本港學生、家長、老師和食物供應商使用。

10

10. 在設有小食部的學校當中,少於四成家長知道其子女在該處購買過何種食物及飲品。

是項調查亦發現,26.4%的家長不知道其子女的飲食是否健康。這些數據意味着家長應加強與其子女的溝通,以更了解他們的飲食習慣。

11. 此外,近四成家長表示不容易養成健康的飲食習慣,因為他們沒有足夠時間預備食

物,並覺得健康食物味道不佳及缺乏變化。因此,有需要推行家長教育以協助他們為子女預備健康食物,為他們提供易於跟從的食譜,並推介適合家長使用的技巧,以鼓勵子女實踐健康飲食及向他們說明健康飲食習慣不難培養。

11

總結

___________________________________________________________________________________

大家均有責任為我們的小學生締造有利環境,以助他們能夠作出明智選擇,選取對自己有益的食物。

12

Background & Objectives

_______________________________________________________________________

The Department of Health (DH) has recorded a rising trend of obesity among primary school students, from 16.4% in 1997/ 98 to 18.7% in 2004/ 05, i.e. almost one in five school children is obese. In this light, initiatives which aim at preventing childhood obesity should be implemented.

Promoting healthy eating habit among school children is one of the new initiatives in the 2005-2006 Policy Address. To prepare for the coming territory-wide “EatSmart@school.hk” campaign organised by DH, a Baseline Assessment of Promoting Healthy Eating in Primary Schools has been conducted in the first quarter of 2006. The results of this study would be used as a reference in developing relevant health promotion resources and for subsequent evaluation of the Campaign.

The objectives of this study were:

? To study the knowledge, attitudes and practices on healthy eating among primary

school students and the attitude towards healthy eating in school among the parents; ? To investigate the nutritional environments among primary schools, such as types of

food available in lunch boxes, tuck shops and vending machines, and policy stipulated by schools;

? To find out factors affecting students’ eating behaviour and promotion of healthy

eating in primary schools; and

? To give recommendations on strategic and resources development of

“EatSmart@school.hk” campaign.

13

Research Methodology

_______________________________________________________________________

Primary 4 and Primary 5 students, their parents and principals/ school representatives of primary schools in Hong Kong were selected to participate in the study by a stratified cluster sampling method. A total of 44 schools were drawn in proportion to the number and types of schools in each district.

Three separate sets of self-administered questionnaires for students, parents and school principals/ representatives were designed by DH. The final sets of questionnaires were administered between 13 February and 6 March 2006 after a pilot test in January 2006.

A total of 9,831 sets of questionnaires for students and parents were distributed, with 9,222 questionnaires for students and 9,014 for parents returned. The corresponding response rates were 93.8% and 91.7% respectively. As for the questionnaire for schools, all 44 recruited schools returned their questionnaires. The response rate for schools was 100%.

14

Key Findings of the Study

_______________________________________________________________________

Demographics

Among the participating students, the demographic profile in terms of class and sex was similar to that of the student population of Primary 4 and Primary 5 in Hong Kong, consisting of 48.5% Primary 4 and 47.9% female students.

The majority of participating parents were female (77.2%), about 60% had secondary education attainment and about one quarter (24.6%) attained post-secondary education or above. Sixty percent of them had household income below HK$20,000.

Among the participating schools, slight difference in the school type was noted between the sample and the profile of primary schools in Hong Kong. Most of the participating schools were whole-day (93.2%) and co-educational (97.7%) schools. Forty-eight percent were Catholic or Christian schools whilst 45.5% did not have religious background.

Students’ perception of their own eating habit

According to the study, most of the students claimed that they had a very healthy, healthy or acceptable eating habit (89.4%), while only 3.6% of the students said their eating habit was unhealthy or very unhealthy.

Knowledge on healthy eating

Students were asked to choose the healthier options among six different pairs of food or drinks. They were also tested for ability to rank food groups correctly in the Food Guide Pyramid. In general, they had good knowledge on healthy food with the mean Knowledge Index of 8.1 out of a 10-point scale.

15

The subgroup analysis showed that the mean Knowledge Index (KI) of female students was significantly higher than that of male students by 0.5 point (8.4 vs. 7.9, p<0.0001).

Attitude on food preference

Attitude Index (AI) of students on food preference showed that the students generally did not favour healthy food. Mean score of the AI was only 2.6 out of a six-point scale. In particular, 18.9% of the students scored zero. Among the six food pairs, it is noteworthy that more students showed preference on unhealthy food such as hamburger with French fries, fried rice noodles with beef, ice-cream and hot dog.

The subgroup analysis showed that female students and those perceiving themselves as healthy (both with mean AI 2.8) had better attitude on food preference than their counterparts, where the means of male students and those perceiving themselves as unhealthy were 2.39 and 1.84 respectively (p<0.0001). Besides, students with higher KI were found having higher AI (p<0.0001).

Students’ eating practice

Students’ eating practice was evaluated based on whether they had breakfast and their daily eating frequency on different types of food.

The majority (85.7%) of the students had breakfast on the day of the survey. Concerning their daily food consumption, most of them (70.7% to 93%) consumed dairy products, vegetables, grains and cereals, meat, fish, eggs, peas and beans in appropriate frequency. Only about half, however, had a healthy habit of eating fruits (56.7% ate twice or more per day). Besides, only 8.7% to 24.7% of the students did not take unhealthy food such as drinks with added sugar, fried and deep-fried food, food high in sugar, food high in fat and food high in salt.

16

Similar to the AI, a rather low mean of Practice Index (PI), 5.3 in a 11-point scale was obtained. The subgroup analysis showed that the following groups of students had a significantly higher mean PI than their counterparts: (1) female (5.47 vs 5.22 (male), p<0.0001); (2) parents made decision on food at home (5.40 vs 5.01 (student), p<0.0001); (3) perceived their diet as healthy (5.44 vs 4.30 (unhealthy), p<0.0001); (4) studied in whole-day schools (5.36 vs 4.89 (half-day schools), p<0.0001). The PI of students was found significantly associated with AI and KI (p≤0.0001).

Parents’ perception of their child’s eating habit

Consistent with students’ own reporting, most of the parents claimed that their children (72.9%) had breakfast everyday. A majority of them (82.6% to 97.6%) indicated that their children consumed grains and cereals, meat, fish, eggs, peas and beans, vegetables and fruits at least once per day at home. Not many parents (64.8%) were aware of their children eating habit on dairy products. On the other hand, only 5.5% to

6.9% of the parents claimed that their children never took food high in sugar, fried and deep fried food, drinks with added sugar. Ten percents and 20.6% of the parents claimed their children never ate food high in fat and salt respectively.

For those schools with tuck shops, less than 40% of the parents knew what kind of food/ drinks their children bought there. When asked whether their children brought snacks to school, more than half of the parents (61.6%) said their children did so, and the popular snacks were biscuit (69%) and candy (33.8%).

In contrast to students’ own perception, only over half of the parents (58.3%) considered their children’s eating habit as healthy. It is noteworthy that 26.4% of the parents did not have any idea on the healthiness of their children’s diet.

Nearly two-fifth of the parents (39.3%) claimed that healthy eating was not easy to sustain, with the common reasons such as “having no time to prepare healthy food” (28.4%), “healthy food does not taste good” (25.7%), and “healthy food lacks of variety” (17.1%).

17

Consideration in choosing food

Among the students, cleanliness and hygiene was the top consideration when choosing food (81.9%), followed by taste (67.1%), freshness (63.8%), nutritional value (62.1%) and price (53.5%).

Parents opined that cleanliness and hygiene (81.5%) was together the key consideration in choosing food, followed by nutritional value (77.5%), freshness (70.9%), preference and taste of the children (64.6%). Besides, taste (41.9%) and price (39.6%) also played a role in choosing food for children.

Consideration in choosing lunch caterer

For choosing lunch caterer among school representatives, nutritiveness and healthiness of food together was the most important factor, with a total score of 1,313, followed by record of food safety incident (scored 610), company size (scored 525), food price (scored 519) and taste of food and food preference of students (scored 492).

Measures to promote healthy eating habit

Regarding measures to promote healthy eating habit, both parents and school representatives strongly supported offering health education to students (59.8% and 84.1% respectively). Promoting healthy eating policy in school also received considerable support from parents and school representatives (51.1% and 51.3% separately).

Schools’ eating environment

Nearly 62% and 48% of the primary schools had healthy lunch or snack policy respectively. However, about three-tenth (27.3%) of the primary schools did not have any healthy eating policy.

18

Most schools arranged lunch to students either through ordering lunch boxes from food caterers (81.4%) or commissioning caterer to serve lunch at school (17.3%). Lunch caterers (82.9%) and teachers (77.2%) were the major decision makers on school lunch menus. Most of the schools had drinking fountain facilities (83.1%), while about half had tuck shops (53.9%) or vending machines (56.5%). The vending machines in school mostly provided drinks with added sugar in packets or bottles (95.3%), fresh milk and soya milk (75.7%) and distilled water/ mineral water (63%).

The study also showed that most of the primary schools did not stipulate many regulations on lunch caterer or tuck shop/ vending machine contractor. The mean Regulation Index (RI) for school was very low (3 out of a 10-point scale). Among those schools with regulations, about half or less than half of them requested the selling of healthy food including fruit juice or dried fruits (52%), fresh fruit (45%) and vegetable (36%) in the tuck shops, and 52% of them restricted the selling of drinks with added sugar in the vending machines. Similarly, less than half of them (42.7%) stipulated the amount of vegetables in the lunch box. In contrast, there was a strong demand from parents for stipulations on the amount of major food groups (85% to 90%), including vegetable and fruit, to be provided in lunch and compulsory sale of fruit (63%) and vegetable (56%) in tuck shop.

Factors contributing to students’ eating practice

The linear regression showed that students’ eating habits were mainly associated with (1) student’s perception on his/ her diet as healthy (coefficient=0.74, p<0.001), (2) parents’ perception on their child’s diet as healthy (coefficient=0.34, p<0.001), (3) students with home-provided lunch (coefficient=0.34, p=0.007), (4) restricted sale of drinks with added sugar at tuck shop (coefficient= -0.25, p<0.001), (5) students’ attitude on eating preference (coefficient=0.22, p<0.001).

19

These factors altogether accounted for about one-tenth (11.5%) of variations of students’ eating practice. The result should be interpreted with caution that there were other factors influencing the students’ eating practice, such as familial factors, product marketing, food availability and influence of mass media which were not investigated in the study. Moreover, the computed PI was derived from non-validated food frequency questions and the cut-off between healthy and unhealthy habit was a best estimate only.

20

Recommendations

_______________________________________________________________________

Some recommendations based on the study findings:

1. The study results showed that both parents and school representatives supported

offering health education to students (59.8% and 84.1%) and promoting healthy eating policy in school (51.1% and 51.3%). Moreover, nearly 40% of the participating schools supported more parental education and collaboration with the parents. This provides a strong basis for the “EatSmart@school.hk” campaign that students, their parents and the nutritional environment in school should all be targeted for intervention. Indeed, overseas experience has shown that multi-dimensional approaches could make a more significant impact on promoting healthy eating in school.

2. There was a definite knowledge-attitude gap where healthy eating is concerned.

Students generally had good knowledge on healthy food (mean KI 8.1 on a 10-point scale) but fair attitude and practice towards healthy eating (mean AI 2.6 on a six-point scale and mean PI 5.3 on a 11-point scale). A large proportion of students (89%) perceived their eating habits as at least acceptable, in contrast to the relatively unsatisfactory mean PI. Thus, any nutritional education programme with students as target groups should put greater emphasis on shaping a positive attitude towards healthy eating and the building up of a healthy eating practice. For example, creative online game and experiential learning such as cooking competition may help students transfer their knowledge into practice with fun. To ease the workload of teachers, development of teaching resources that can be readily used in classroom sessions or extra-curricular activities could be considered.

21

3. Most of the parents (83%) were the decision makers on food at home. Parents could

serve as role models for children and play a crucial role in teaching children how to make healthy choices. Although parents may prepare lunch and snacks for students, their relative influence over food provided at school is much lower. About 90% of the schools had working groups to monitor the catering service for students, but only 70% of the working groups consisted of parent representatives. Moreover, a majority of the parents had no idea on the types of food and drinks available to their children at school tuck shops and vending machines, where unhealthy items such as energy-dense food and drinks with added sugar were commonly found. Thus, parents should be more actively engaged and empowered to work with the school management in promoting healthy eating in school. For example, parents could be encouraged to participate in the formulation of healthy eating policy, to join the catering service working group, to select catering service providers and monitor their performance or help out at school as volunteers during lunch breaks and recesses. Parents can be provided with practical ways to prepare healthy lunch and snacks through publicity activities and educational materials.

4. At present, only 60% of schools had healthy lunch policy, and one half of all schools

did not stipulate any requirements for their lunch caterers. Therefore, it is not surprising to find that students who brought their own food or had food delivered by parents had a healthier eating practice. There is much need for schools to develop a healthy lunch policy. In this respect, the “Nutritional Guidelines on School Lunch for Primary School Students” produced by DH should be widely promulgated to schools for their inclusion in the contracts with lunch caterers, as well as for monitoring by the users, namely students, parents and schools.

22

5. Both schools and parents viewed nutritional value as a major consideration in

choosing food. However, students regarded hygiene, taste and freshness of food as more important factors. Among the parents who perceived that healthy eating was not easy to sustain, 26% of them thought that healthy food did not taste good. It is therefore important that food traders should provide not only healthy but also hygienic and tasty recipes for students. Communication between schools/ parents and the food traders, together with the encouragement from parents/ students are crucial for a paradigm shift in concept to that healthy food is also delicious and attractive.

6. It was found that more than half of the schools had tuck shops (53.9%) or vending

machines (56.5%). It is not unusual for students to buy their favourite food from tuck shops or vending machines as lunch substitutes and snacks. As noted earlier in this section, many unhealthy food items were available at tuck shops and vending machines. With many unhealthy food items available to choose, students were likely to select and eat unhealthy snack. A qualitative study conducted by DH in 2004 also indicated that healthy food was seldom available in school. To facilitate easier making of healthier choice, DH’s “Nutritional Guidelines on Snacks for Primary School Students” about choosing healthy snacks should be widely disseminated to schools for their reference in establishing healthy snack policy and making contractual agreement with their tuck shop and vending machine providers.

7. Schools should liaise with lunch caterers, tuck shop owners and vending machine

operators regarding food provision for schools to specify clearly on the various requests and restrictions on food. It is important for lunch caterers, tuck shop owners and vending machine operators to understand their important roles in keeping students healthy. Commitment to the agreed regulations and regular reviews on the performance are important for reaching the ultimate goal of establishing healthy eating practice among primary school students.

23

8. Various marketing surveys commissioned by DH in the last few years have

consistently shown that advertisements in the mass media, especially those on TV, remained the most common source of health information for the general public. With the experience of launching the “2 plus 3 a day” campaign which promotes optimal health by eating at least two servings of fruits and three servings of vegetables as part of a balanced diet every day by DH, it is advisable for the Department to carry on launching campaigns for drawing students’ and parents’ attention to eat more healthy food and say “no” to the unhealthy ones. Many studies have found campaign messages which disseminated through mass media including TV, radio, newspaper, and advertisement are effective in reaching a large number of target populations for raising awareness and changing attitudes.

9. In order to keep a place with comprehensive healthy eating information for others’

easy reference, a thematic website like “Eat Smart, Play Hard” organised by the Food and Nutrition Service, Department of Agriculture of the United States () or the above-mentioned “2 plus 3 a day” campaign conducted by DH (), is suggested to be setup for students, parents, teachers and food caterers.

10. For those schools with tuck shops, less than 40% of the parents knew what kind of

food/ drinks their children bought there. The study also found that 26.4% of the parents had no idea on the healthiness of their children’s diet. These figures implied that parents should enhance communication with their children in order to know more about their eating habits.

11. Moreover, nearly two-fifth of the parents (39.3%) said that healthy eating habit was

not easy to sustain as they did not have enough time for food preparation and found that healthy food is tasteless and short of variety. Parental education should be provided to help the parents prepare healthy food for their children, to provide easy-to-follow cooking recipes and to introduce parental skills of encouraging children to eat healthily.

24

Conclusion

_______________________________________________________________________

It is everyone’s responsibility to create a supportive environment in helping our primary school students to be able to make the wise choice and choose good food for themselves.

25

-

关于健康饮食的调查报告

关于健康饮食的调查报告随着社会经济的发展人们生活水平得到了很大的提高健康也随之成为现代人追求的目标但一些健康问题总是在考验和挑战我…

-

关于饮食安全的调查报告

关于食品安全问题调查报告09070122沈仁芳五花八门的食品安全问题频频曝光当今消费者当何去何从食品市场的确让人担忧从避孕虾地沟油…

-

关于食品安全问题的调查报告

关于食品安全问题的调查报告电气2班张寿丰张瑜周太鸿周宵亮指导教师林贵长摘要民以食为天我们生存离不开它但是我国接连不断发生的恶性食品…

-

关于健康饮食的健康调查报告

关注自我从健康开始中学生饮食营养健康调查报告中学时代是学知识长身体的重要阶段同时也是良好的饮食习惯形成的重要时期这个阶段掌握一定的…

-

大学生饮食情况调查报告

摘要近年来我国政府越来越重视推广居民营养膳食的科学化确实饮食习惯的良好与否极其重要一个人的饮食习惯代表了其生活方式大学生作为即将踏…

-

饮食与健康调查报告

调查:刘燕“民以食为天,食以洁为本”,这是大家都明白的道理。随着近几年的不断发展,人们对饮食健康越发的重视,新闻媒体对食品安全方面…

-

关于中国食品安全问题的调查报告

关于中国部分地区食品安全问题的调查报告淮南市田家庵区一、调查背景食品,对于人类来说是必不可少的,自古以来存在着一个人人皆知的道理,…

-

关于客家饮食文化的调研报告

关于贺州市客家饮食文化的调研报告独树一帜的客家饮食文化,客家人就像是一个以味觉写成的民系。客家是中华民族中汉族的一支特殊民系,两千…

-

关于食品安全的调查报告

关于食品安全的调查报告班级:24班对过姓名:毒灵儿学号:20xx14内容摘要:食品是人类生存和发展的最基本物质,对于食品而言,安全…

-

关于健康饮食的调查报告

关于健康饮食的调查报告随着社会经济的发展人们生活水平得到了很大的提高健康也随之成为现代人追求的目标但一些健康问题总是在考验和挑战我…

-

我们的饮食习惯调查报告

一、背景与意义随着生活水平提高,肥胖率逐渐升高,紧张的学习使部分学生生活饮食无规律,营养不良,人们开始对食物越来越挑剔,越来越苛求…