关于辞去董事职务的申请

关于辞去董事职务的申请

贵州浪人网络科技发展有限公司董事会:

本人因为个人原因,请求辞去在贵州浪人网络科技发展有限公司董事会董事的职务,希望董事会批准。

衷心祝愿浪人集团的明天更加兴旺发达!

此致!

敬礼!

申请人:

申请日期:

第二篇:董事的职责

Sarbanes-Oxley requires directors to have an independent, substantiveview of the inner workings of the company—including technical and

financial perspectives on its operations and its future prospects.

How are you going to do that?

What’s a Director to Do?

by Michael C. Jensen and Joe Fuller

The speed with which boards, analysts, auditors,investment bankers, lawyers, and banks have

moved to lay the blame for every corporate misdeedat the feet of CEOs and others reflects both a

measure of truth and a degree of guilt.

Michael C. Jensen is Managing Director of Organizational Strategy at Monitor.Professor emeritus at the Harvard Business School, Jensen is the author ofFoundations of Organizational Strategyand Theory of the Firm: Governance, ResidualClaims, and Organizational Forms,both published by Harvard University Press. Jensenwas elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1996.

Joe Fuller is CEO of the Monitor Group, a family of professional firms located in

Cambridge, MA.

Executive Highlights

Three Steps to Creating an Independent

Perspective on the Company’s Inner Workings

1.Emphasize clarity. Do you really understand the risks inherent in what you have justratified? If not, does the board have its own budget to hire outside technical expert-ise to help them understand and make critical choices?

2.Move from the simple legal requirement to care toward the more important duty tobe curious and question assumptions. Does the board have regular, planned meetingswith the entire top management team and opportunities to interact privately withkey managers?

3.Decide who gets to decide. Who picks who goes on the board? Which committeesthey sit on? Separating management and control rights is a fundamental tenet ofbusiness. However, it is one that has rarely been put to use in the boardroom. Thatneeds to change.

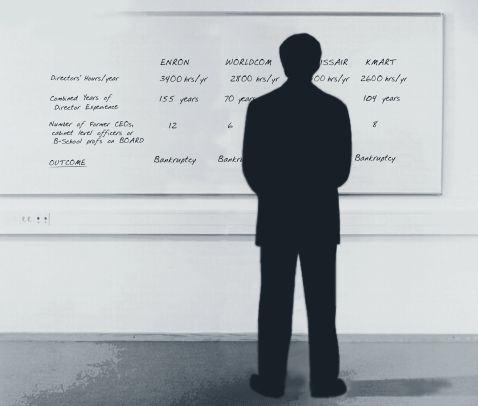

Every wave of corporate turmoil or malfeasance inevitably leads to a

discussion about the role of the board. So it is not surprising thatthe current wave of scandals has set off yet another maelstromabout corporate governance. It was, after all, only a few decades ago thatshareholder advocates took boards to task for being asleep at the wheel whenthe Japanese overtook American industry in the 1970s. They pilloried boardsagain in the late 1980s for letting managers live high on the hog with theshareholders’ dollars—remember the 24 country club memberships the share-holders bought for RJR Nabisco’s CEO, Ross Johnson.1

Copyright Michael C. Jensen and the Monitor Group 2002MONITOR GROUP1

And so, it comes as no surprise that the current wave of accounting scandalshas once again dragged an otherwise fairly anonymous group of people—corporatedirectors—into the spotlight. Indeed, in the wake of these scandals, a barrage of new legislation has rolled over corporate directors. These

new requirements, including the recently passed Sarbanes-

Oxley bill and new regulations by the SEC and the NYSE,

NASDAQ, and Amex securities exchanges, all attempt to

address corporate abuses and boost confidence in U.S. secu-

rities markets. The new rules focus on more timely and transparent financial disclosure;greater accountability for financial reporting; increased oversight and independence ofthe audit function; enhanced SEC review of financialstatements and enforcement ofregulation; and broader remedies for violations.

Not surprisingly, these new regulations create potential additional personal liabil-ity for directors. In the past, directors had to focus their attention only on ensuringthe company’s compliancewith procedural rules to protect themselves. That is, theyhad to act with reasonable care to vouchsafe what they believed to be the company’sbest interests, and they had to ensure that management did not perpetrate fraud, actin bad faith, or harbor personal conflicts of interest with the company. Under mostcircumstances, the courts applied what is generally known as the business judgmentrule, which protects boards by prohibiting the courts from hearing cases in which out-siders, including shareholders, questioned the business judgment of the board.2

If a company followed the letter of the rules, board members could serve in relativesafety. They could lay all but the most egregious failures at the feet of others such asmanagers, lawyers, investment bankers, consultants, and auditors. However, merelycomplying with the rules won’t pass muster anymore. In fact, the new legislationrequires senior managers to certify that they have implemented procedures to gatherall “material” information about the business. Moreover, management must haveeither the audit committee or the independent members of the board validate thatattestation. The legislation also stipulates that every board should have at least one“financial expert” who, through education and experience as a public accountant orThese new regulations createpotential additional personal liability for directors.2What’s a Director to Do?

auditor or a principal financial officer, comptroller, or principal accounting officer of acompany, or from a position involving the performance of similar functions, has:

An understanding of generally accepted accounting principles and

financial statements;

Experience in (i) the preparation or auditing of financial statements

of generally comparable companies, and (ii) the application of such

principles in connection with the accounting for estimates, accruals,

and reserves;

Experience with internal accounting controls; andAn understanding of audit committee functions.

Clearly, the bill’s authors intend to render mute any future defense predicated on aboard’s lack of oversight responsibility or of technical skill.

In addition, the legislation calls for new processes to collect and disseminate infor-mation on corporate performance, new faster reporting cycles, and a clear obligationto certify that financial reports “fairly present in all material respects the financialcondition and results of operations of the issuer.”3Yet, it is fair to say that few, if any,boards can satisfy these conditions as currently constituted. We know now that evenboards lauded in the past for their work failed to meet the emerging expectations.Ironically enough, Chief Executivemagazine voted Enron’s board among the best everin 20004, and the business press frequently quoted Tyco’s CEO, Dennis Kozlowski—who

“now stands indicted on charges of racketeering, fraud, tax

Whenever an institution evasion, grand larceny, and misuse of company funds5—as

a strong advocate of good corporate governance, strong

boards, and directors with backbone. In his words: “We are

offended most by the perception that we would waste the

resources of a company that is a major part of our life and

livelihood, and that we would be happy with directors

who would permit that waste…So as a CEO, I want astrong, competent board; one that can advise me and mymalfunctions as consistently as boards of directors have in nearly every major fiasco of the last forty or fiftyyears, it is futile to blamemen. It is the institution

that malfunctions. - Peter Drucker ”

Copyright Michael C. Jensen and the Monitor Group 2002MONITOR GROUP3

staff how to continue succeeding.” Indeed, he served as a literal poster boy for goodgovernance when he was featured in a cover story in the Spring 2000 edition ofDirectors & Boards.He also adorned the cover of BusinessWeekin the spring of 2001.6 However, rather than wring our hands and wonder what went wrong in any particu-larcase, we would do well to listen to the wisdom of Peter Drucker when he said:“Whenever an institution malfunctions as consistently as boards of directors have innearly every major fiasco of the last forty or fifty years, it is futile to blame men. It istheinstitution that malfunctions.”7Indeed it is. As long-time observers of boards,we are optimistic that some of the unfortunate scandals that have wrackedAmerican business of late can serve as stepping-stones to better and more effectivegovernance reforms.

We believe, for example, that small changes in board composition or committeemembership are unlikely to bring the kind of change that the current environmentdemands. Boards instead would do well to change fundamentally their approach to thejob at hand. Wise CEOs will want their boards to do so, not only to soothe restive insti-tutional shareholders and regulators, but also to reduce the probability of future prob-lems in their companies.

How can boards fulfill these new mandates? They should focus on the followingareas:

Be clear about the DECISION RIGHTSand ROLEof the board. Many years ago Eugene Fama and Michael Jensen suggested a compelling frameworkfor understanding the proper role of the board8. The foundations of this structure liein an understanding of the inherent nature of agency costs—the costs which ariseanytime human beings attempt to engage in cooperative effort, including the cooper-ation inherent in the modern corporation. When people (including managers) makedecisions for which they do not personally bear the full costs or benefits, the organi-zation and society is at risk. That risk arises less from the prospect of malfeasance orfraud, but rather from self-interest and the human tendency to avoid blame.4What’s a Director to Do?

We can decompose any major decision into a sequence of sub-decisions in the decision process. They are:

the right to initiaterecommendations for resource allocations or contracts,

the right to ratifythose initiatives,

the right to implementthe ratified initiatives, and

the right to monitorthose decisions.

Monitoring rights include not only the right to measure and evaluate, but also theright to reward and punish performance. We generally assign the initiation and imple-mentation rights to the same party, and, hence, we call these the “managementrights,” while simultaneously assigning to a separate party the ratification and moni-toring rights, the “control rights,” essential to disciplining managerial behavior.

When control is effective in an organization, the management rights for a decisionare separated from the control rights for that decision. In this situation, the typicalmanager will be exercising both management rights and control rights—control rightsover decisions made by subordinates, and management rights for decisions for whichhis or her superiors hold the control rights.

We must separate the management rights from the control rights at all levels in theorganization to reduce aberrant behavior. This is especially true at the board level.Doing so will bring a new level of stability and oversight to corporate governance. Thisproposition thus generalizes to the governance structure the long-standing separationprinciple of controllership: that one should not allow a person receiving cash to be thesame person who records its receipt.

Applying this formula to the board would yield the following decision-makingmodel: The board must hold the top-level control rights in the organization, includingthe rights to initiate and implement certain decisions such as the right to hire,evaluate, compensate, and fire the top management team, board members, and thecompany’s auditor. The board must also hold the right to ratify and monitor othermajor decisions such as those pertaining to changes in fundamental strategic direc-

Copyright Michael C. Jensen and the Monitor Group 2002MONITOR GROUP5

tion. This implies that the chairman of the board cannot be the CEO because a chair-man’s main job is to set the agenda of the board and to oversee the hiring, firing, andevaluation of the top management team—and no CEO can effectively run the processthat evaluates himself. The annual election of directors by shareholders accomplishesthe same principle of separation for the board of directors.

Similarly, applying this formula to the board might lead some to adopt the modelof non-executive chairmen used by some European companies. Academics and stu-dents of corporate governance have long debated the respective merits of executiveand non-executive chairmen. Recent events will undoubtedly rekindle that debate andmay decisively tip the balance in favor of the non-executive model. The attractivenessof that approach stems not only from the hope that non-executive chairmen wouldhave interdicted the cycles of managerial self-delusion, hubris and, in some cases, out-right fraud that destroyed some prominent companies and undermined trust in thecapital markets, but also from pure workload considerations. Admittedly, a moreinformed, independent perspective might have helped prevent some of the abuses.But, as we look to the future, the logic for a non-executive chairman becomes com-pelling, simply as a function of the workload responsible board chairmen will bear.Chairmen will have to ensure that each of several committees fulfills its statutoryresponsibilities under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act and additional administrative responsi-bility as stipulated by the SEC. New requirements from the European Union and otherjurisdictions will undoubtedly follow. Moreover, the capital markets will certainly wel-come, if not demand, more mechanisms to assuage anxieties over the potential forfuture abuses. Companies that choose to take the lead in this regard might well enjoythe type of plaudits that Coca-Cola earned by assuming a leadership stance on theexpensing of options.

Focus on changing the STRUCTURAL, SOCIAL, PSYCHOLOGICAL,and POWER ENVIRONMENTof the board.

For all intents and purposes, the directors at most companies are employees of theCEO. The CEO does most of the recruiting for the board and extends the offer to jointhe board. And, except in unusual cases, board members serve at the pleasure of theCEO. Moreover, it is rare that the board meets outside of the CEO’s presence or with-6What’s a Director to Do?

out his explicit permission. Finally, virtually all information board members receivefrom the company originates from the CEO, except in highly controlled or unusualcircumstances. A change in these practices will require a major change in the powerrelationship between the board and the CEO, perhaps going as far as a structuralseparation between the chairman’s and CEO’s positions. Companies can implementseveral practical steps immediately to infuse more balance into the board’s deliberations.They include:

The board should have its own budget for purchasing advice from outsideexperts of various sorts—consultants, lawyers, financial, and other experts. TheAudit and Compensation Committees must become the true clients of the auditorsand compensation consultants. That suggests locating the decision rights for choic-es previously made by management, and the associated budget authority, to boards.

The board should have regular, planned meetings with the entire top management team and frequent opportunities to interact privately with keymanagers. Boards must create opportunities to come to know on a personal basis theindividuals on whose abilities and judgment the shareholders rely. The carefully cho-reographed and often perfunctory board “grand performances” of the past must bereplaced by selective, but nonetheless substantial, dialogue. Management must notonly expect, but also encourage more frequent dialogue between directors and keyoperating and functional managers on key elements of the strategy. The board, in itsduty to evaluate the CEO and other top managers, can productively implement theprinciple of 360-degree evaluation, and it should not happen by accident throughback channel conversations.

The board must take firm control over not only its own processes, but alsoits own composition.That requires employing the newly required NominatingCommittee as a vehicle for building the board’s ability to exercise its expanding roleeffectively. Just as auditors and compensation consultants should treat companyboards as their clients, so should the executive search firms that identify board candidates. The CEO should become a participant in a board-sponsored process ofrecruitment, rather than serving as the chief recruiter. One straightforward implica-tion—the chairman of the Nominating Committee or the non-executive chairman of

Copyright Michael C. Jensen and the Monitor Group 2002MONITOR GROUP7

the board should extend the invitation to serve to new board members, not the CEO.This will help avoid the situation in which board members feel indebted to the CEO.Moreover, the composition and performance of the board should become an active topic of conversation during executive sessions and between the board andmanagement.9

We must also be aware that to recruit and retain high quality board members, boardcompensation will have to increase substantially to reflect the increased legal and rep-utational risks that such membership entails in this new environment. This too willgenerate controversy, but we see no way around it. In addition, to encourage poten-tial board members to self-select in or out based on whether they truly believe theycan add value, we should require a meaningful personal cash investment in the firm’sequity that will be restricted for the entire period of the members’ service on theboard. This investment should not be less than $100,000, and cannot be satisfied bya gift of options or restricted stock by the company. Board members with such per-sonal stakes in the company will be less likely to view themselves as employees of theCEO and will have additional psychological, social and economic justification for anindependent voice in difficult board discussions and decisions. In general we shouldencourage the role of active investors, that is those individuals and organizations thathold substantial amounts of equity and/or debt and play an active role in the strate-gic direction of the company.

Beyond this structural and cultural shift,

PHILOSOPHICAL SHIFTSare NECESSARY.

First, the mindsets of boards must move from one of careful review to one of insatiable curiosity.10The duty to care has long stood as the principal legal hurdle fordirectors. We must now add to that a new duty—one of informed inquisitiveness.Question assumptions. Make note of and probe anomalies. If the company’s expecta-tions lie outside those that experts generally view as plausible for the firm’s industryin terms of growth, profit margin, or return on assets, its board must investigate theassumptions underlying such projections. Directors must answer a fundamental ques-tion about such a company—what observable sources of competitive advantage allow8What’s a Director to Do?

it to outperform its market so consistently? Directors must not be content to concludethat growth rates arising from “stretch” goals designed to stimulate the organizationto excellent performance will lead ineluctably to outstanding performance. Indeed,that constitutes little more than wishful thinking. Moreover, boards should take per-sonal responsibility for understanding how traditional budget processes and stretchgoals frequently inculcate a lack of integrity in an organization and destroy value.11They must play a role in reforming these systems.

Second, directors must move beyond a single-minded, legalistic focus on complianceand focus on clarity. This represents more than getting the footnotes right or engag-ing the right auditors. Instead, the current situation requires setting forth a trulyaccurate picture of the company and communicating that picture to shareholders.Rarely do board members have the kind of information they need to assess accuratelythe progress of the corporation; getting that information requires boards to overhaulthe process by which they get substantive information about corporate performancefrom one controlled by the CEO to one in which the board has ready access to relevantinformation from unimpeachable sources. Board members must understand the keystrategic dimensions that determine the company’s competitive position, the factors that drive the logic of value creation, review progress against those drivers reg-ularly and audit the company’s performance against relevant measurements acrossthose dimensions from year to year.

Individual directors have tried in the past to do the things we have suggested eitherin whole or in part. And yet, few ever succeeded consistently. Consider the case of for-mer Supreme Court Justice Arthur Goldberg, a member of the board of TWA, who askedto form a committee on operations.12He intended this committee to get periodicreportson the company’s progress and receive support from a cadre of outside experts, includ-ing scientists, economists, public relations people, and financial engineers.Management denied his request, and he subsequently left the board. Presumably, hehad realized that he didn’t have the necessary information to do the job and preferredto maintain his intellectual integrity at the expense of his position.

Copyright Michael C. Jensen and the Monitor Group 2002MONITOR GROUP9

Indeed, it is our belief and our great hope that ruined reputations, corporate valuedestruction, and new laws will do more than force directors to do the job they havelong been employed to do. Rather, they will encourage them to do that job more con-fidently and competently, as well as cause management to support them unreservedlyin that work.

HONESTYand INTEGRITY:

Easy to assert, Difficult to implement.

Honesty and integrity constitute matters of human behavior and human choice. Nocombination of rules, punishments, and threats can substitute for men and women ofintegrity who bring principles to the boardroom and apply them. Laws and regulationscan help establish an environment that encourages honest behavior and punishes vio-lations. But human choice and allegiance to these principles are critical. If companiesare to behave with more integrity than we are currently observing, the people in themfrom the board of directors on down must come to better understand the nature ofthese choices. Boards must take seriously their responsibility to ensure the integrityof the organization in all matters. Even more importantly, board members must bewilling to incur costs to do so.

Everyone espouses allegiance to principles such as honesty and integrity. Yet, evi-dence from human behavior indicates that when it really matters, people very oftenchoose to abandon the very standards they espouse. And this includes not only CEOsand directors, but also government and religious officials. It is now time for corporatedirectors to think carefully about how to restore integrity in corporate governance.This is not an easy task. It will only come when men and women of principle not onlyconfront substantive, difficult business questions honestly, but also change inbredbehaviors which encourage many of them to avoid painful confrontations and diffi-cult trade-offs. The current tragic circumstances make this transition easier, as theconsequences of unethical or illegal behavior, including ruined reputations, ruinedcompanies, and criminal prosecutions for once-feted executives, are unambiguous toeven the most cavalier and insouciant directors.

10What’s a Director to Do?

Honesty and integrity in our actions and words are most valuable to otherswhen it costs ussomething to adhere to them. When it costs us nothing, it gen-erally follows that the associated actions are worth little or nothing to those whodepend on us. Yet, it is in those circumstances in which values count the most tothose with whom we deal (that is, situations in which it is costly for us to behonest) that people inevitably prove most willing to suspend those qualities andforgive themselves those obligations. Indeed, in granting ourselves such forgive-ness, we assuage our guilt by finding ways to blame others. The speed with whichboards, analysts, auditors, investment bankers, lawyers, and banks have moved tolay the blame for every corporate misdeed at the feet of CEOs and others reflectsboth a measure of truth and a degree of guilt. And, in the ultimate corruption ofprinciple, we abandon these principles not only to lower the costs on ourselves andothers, but also to “protect” the reputation of the institutions we serve. Consider,for example, the current troubles that many corporations, auditors, investmentbanks, and other institutions in which those responsible appear to have over-stepped ethical bounds to protect their organization from short run damage. Thesetendencies—to avoid short-term pain at the cost of far greater long-term harmand to lose one’s sense of personal responsibility in favor of institutional inter-est—are far more prevalent and dangerous than most observers care to admit.Sadly, such actions usually end up imposing far greater cost on these organizationsthan those that would have been incurred by straightforward and early confronta-tion with the pain.

In the end, legislatures will pass new laws, regulators will promulgate new rules,and the climate of capital markets will change. But restoring integrity to the sys-tem will, ultimately, occur one step, one director, one audit committee, one board,and one organization at a time. It will require men and women of courage and con-viction on boards and in management teams to incur costs in the short run inorder to preserve their reputations and fulfill their duty—the preservation of thevalue of the organizations they serve.

Copyright Michael C. Jensen and the Monitor Group 2002MONITOR GROUP11

ENDNOTES

1.Bryan Burrough and John Helyar, Barbarians at the Gate: The Fall of RJR Nabisco (New York: Harper Perennial, 1991), p. 93.

2.See /areas/research/tobacco/TOB-E17.HTM and

/glossary.php3?glossary_id=15

3.Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, Pub.L. 107-204, 116 Stat. 745 (July 30, 2002) p. 33.

4.Robert Lear and Boris Yavitz, "The Five Best and Five Worst Boards of 2000," Chief Executive, October 2000,/bench/boardsontrial/bestboards.htm

5.Stephanie Strom, "In Charity, Where Does a C.E.O. End and a Company Start?" The New York Times on the Web, September22, 2002, /2002/09/22/business/yourmoney/22CHAR.html

6."This CEO Wants Strong Directors," excerpted in "The Way It Was: 1995," Directors & Boards26:1

(September 22, 2001): p. 107. See also William C Symonds, "The Most Aggressive CEO," BusinessWeek, May 28, 2001,/magazine/content/01_22/b3734001.htm

7.Peter Drucker, "The Bored Board," in Toward the Next Economics and Other Essays, (New York, NY: Harper & Row, 1981), p. 110.

8.Eugene F. Fama and Michael C. Jensen, "Separation of Ownership and Control," Journal of Law and Economics 26 (1983): pp. 301-325, /abstract=94034

9.Ram Charan, Boards at Work: How Corporate Boards Create Competitive Advantage (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1998),240 pgs.

10."The duty of curiosity," is a phrase used by Gwendolyn S. King, director of the National Association of Corporate Directors.See that trade group's publication, DM Extra! Bulletin, January 31, 2002, pp. 2-3,

/members/dmx/dmxtra_0202.pdf

11. Michael C. Jensen, "Corporate Budgeting Is Broken: Let's Fix It," Harvard Business Review, November 2001, pp. 94-101,/paper=321520, and Michael C. Jensen, Paying People To Lie: The Truth About the BudgetingProcess, September 2001, /paper=267651

12. Jay W. Lorsch, and Elizabeth MacIver (contributor), Pawns or Potentates: The Reality of America's Corporate Boards(Cambridge MA: Harvard Business School Press, 1989), pp. 57-58. See also Robert AG Monks and Nell Minow, Power andAccountability (New York, NY: HarperCollins, 1992), /system/pna/chapter3.html 12What’s a Director to Do?

“As long-time observers of boards, we are optimistic that some of the unfortunate scandals that have wrackedAmerican business of late can serve as stepping-stonesto better and more effective governance reforms. ”OTHER ARTICLES BY THE AUTHORS(available on )“An Open Letter to the CEO,” Harvard Business Review,October 2002, by Joe Fuller“Just Say No to Wall Street,” Journal of Applied CorporateFinance, 2002, by Michael C. Jensen and Joe Fuller

Forthcoming in Best Practice:

Ideas and Insights from the World’s Foremost Business Thinkers.Cambridge, MA: Perseus Publishing and

London:Bloomsbury Publishing, May 2002

MJensen@hbs.edu

Joe_Fuller@monitor.com

WWW.MONITOR.COM

-

关于辞去“XXX卫生院院办公室主任”职务的申请书

关于辞去“XXX卫生院院办公室主任”职务的申请书尊敬的院领导:你们好!20xx年初,新领导班子成立,承蒙院领导对我写作能力的信任与…

-

关于请求辞去安监站站长职务的申请

关于请求辞去安监站站长职务的申请尊敬的各位领导你们好首先对我的辞职行为深表歉意我自20xx年参加工作至今负责全镇安全生产监督管理工…

-

关于个人辞去医院副院长职务的申请

关于个人辞去医院副院长职务的申请尊敬的上级领导现在呈现在您们面前的是我的辞去职务的申请书首先感谢领导们对我的信任根据号文件我于年月…

-

辞去现任职务的申请

辞去现任职务的申请尊敬的院领导您好近期我的内心一直十分忐忑想提及此事又难以启齿但经过多日的仔细思考我还是决定递上此份申请向领导表明…

-

辞去现任职务的申请

辞去现任职务的申请尊敬的院领导您好近期我的内心一直十分忐忑想提及此事又难以启齿但经过多日的仔细思考我还是决定递上此份申请向领导表明…

-

辞去现任职务的申请

辞去现任职务的申请尊敬的院领导您好近期我的内心一直十分忐忑想提及此事又难以启齿但经过多日的仔细思考我还是决定递上此份申请向领导表明…