初始排污权核算技术报告

献县欧联玻璃容器有限公司

初始排污权核算技术报告

编制单位:献县欧联玻璃容器有限公司

20xx年9月15日

献县欧联玻璃容器有限公司

初始排污权核算技术报告

1. 企业概况

1.1. 企业基本信息

献县欧联玻璃容器有限公司于20xx年3月挂牌成立。公司前身是献县日新玻璃制品有限公司,20xx年建厂。20xx年10月美国OI公司收购,更名欧文斯献县玻璃容器有限公司。20xx年3月转为民营企业。公司位于献县东外环路与南环路交叉口东北角,占地面积150亩。

欧联公司前身日新玻璃制品有限公司,分别于20xx年6月和20xx年1月建设两个制瓶车间。按规定进行了环评,完工后通过了献县环保局的验收。并且核发了排污许可证。历年来环保部门对公司排污进行了检测。

1.2. 基本情况及项目组成

1.2.1. 基本情况:献县欧联公司总投资5300万元,拥有2座窑炉,6条制瓶生产线,年生产能力13万吨。公司主要生产玻璃包装容器,包括棕料、绿料和白料玻璃瓶,用于啤酒、白酒及各种饮料的包装

1.2.2. 项目组成

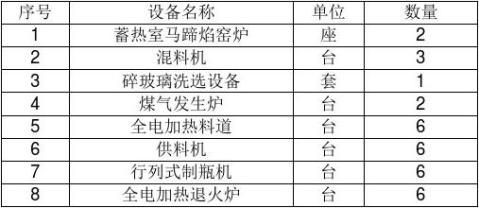

主体工程:两座煤气发生炉,两座玻璃窑炉,六条制瓶生产线及空压站等,附主要设备表。

辅助工程:原料库,成品库。

公用工程:高低压配电设施,办公设施、员工宿舍楼,供水系统,消防设施,食堂等。 环保工程:循环水系统,脱硫除尘设备和SNCR脱硝设备。

附表1. 主要设备一览表

附图1. 厂区平面图

1.3. 物耗能耗

附表2. 主要原料消耗

主要原料性质如下:

石英砂:是一种坚硬、耐磨、化学性质稳定的硅酸盐矿物,其主要成分是SiO2,颜色为乳白色或无色半透明状,油脂光泽,相对密度为2.65,不溶于酸,微溶于氢氧化钾溶液,是重要的工业矿物原料,广泛用于玻璃、铸造、陶瓷及耐火材料工业。

长石:是长石族岩石的总称,是一类含钙、钠和钾的铝硅酸盐类矿物,为地壳中常见的矿物,比例达到60%。长石常见乳白色,但常因含有杂质而被染成黄、褐、浅红、深灰等色,富含钾或钠的长石主要用于陶瓷、玻璃及搪瓷工业。

石灰石:主要成分是碳酸钙,分子量为100.09,属六方晶系,性状为白色粉末,无臭、无味,与稀醋酸、稀盐酸发生泡腾,并溶解。高温条件下分解为氧化钙和二氧化碳,露置空气中无反应。

纯碱:学名碳酸钠,易溶于水,呈弱碱性,在玻璃制品中提供氧化钠。被广泛用于制肥皂、纺织、印染、漂白、造纸、精制石油、冶金及其它化学工业。

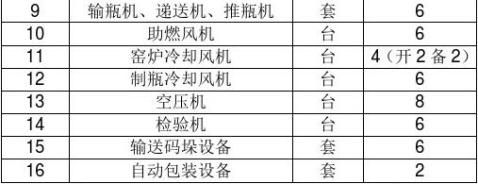

附表3. 能源消耗

产品

玻璃瓶的特点是无毒、无味、透明、不透气,耐热、耐压、耐清洗,化学稳定性好,没有污染。缺点是易破碎。年产各种玻璃瓶2.5亿只。

2. 工艺流程和产污分析

2.1. 工艺流程

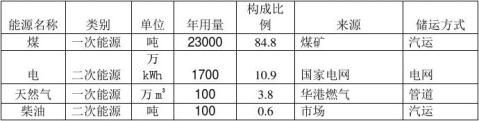

玻璃瓶生产工艺是利用煤气发生炉生产的半水煤气作燃料,在1530℃左右的温度把以石英砂为主的配合料熔化为玻璃液,经过澄清、均化等过程成为适合成型的玻璃态,通过行列式制瓶机制成各种玻璃瓶罐,经过退火、检验和包装后,成品入库。见附图2-工艺流程图

献县欧联玻璃容器有限公司

工艺流程图

玻璃的生产过程主要有以下几个环节:

煤气生产:在煤气发生炉中从底部进入发生炉的空气(一次风)和水蒸气的混合气体(气化剂)与成品煤炭发生氧化还原反应制得半水煤气。煤气经过除灰斗除去煤灰和煤焦油,送往窑炉。燃烧后的炉渣通过除灰器从灰盆出炉。

配料:石英砂、石灰石、长石、纯碱、碎玻璃等原料按照设计配方,经过称量、混合等工序混合为均匀的配合料,通过皮带输送机、斗式提升机等设备送到窑炉的料仓中。

熔化:本公司有二座蓄热式马蹄焰窑炉。煤气和空气分别通过上火侧煤气蓄热室和空气蓄热室吸收其中储存的余热,被加热到1100-1300度通过喷火口进入熔化池混和燃烧。燃烧后的烟气从另一侧喷火口进入回火侧煤气蓄热室和空气蓄热室,烟气经过蓄热室大量的砌体,除去烟尘,在烟气通道中适当的温度区域喷入氨水脱硝,再经过水膜除尘,最后经烟囱排入大气。来自配料岗位的配合料均匀加入窑炉的熔化池,经过分解、熔化、澄清,成为符合要求的玻璃液。

成型:玻璃液从窑炉经过供料道到供料机,用压缩空气吹制成成品瓶。 退火:制瓶机成型后的成品瓶通过电加热退火炉消除应力,提高热稳定性。 检验包装:退火后的瓶子经过自动检验机、灯检,合格的产品包装入库,不合格的瓶子通过废料系统作为原料回收利用。

缩空气吹制成型的,包装设备也使用压缩空气。空压站8台空压机为各工序提供压缩空气。

供电系统:供电局河街变电站10kV 566专线、和城关10kV 596备用线双回路为公司

提供电力。全厂有三台变压器,供给全厂生产生活用电。

供水系统:全厂生产生活用水由献县自来水公司供水管网提供。生产用水主要有空压机冷却水、制瓶机废料冷却水、煤气站水封用水等。冷却水循环使用,不外排。生活污水经化粪池处理后经污水管网排入献县污水处理厂。

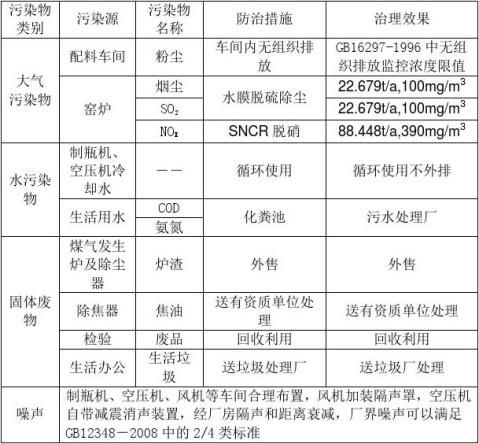

2.2. 主要污染物产生和排放统计汇总见附表4

3. 环保措施及效果

3.1. 污染物防治措施

欧联公司高度重视环保工作,从人力、物力和财力方面提供保证。先后采取多项措施节能减排,至今已经初见成效。

首先,采取先进的工艺技术,降低能源消耗减少污染物排放。公司于20xx年和20xx年投资1100万元对两个车间窑炉进行了节能改造,疏通了蓄热室,更新了小炉。使得吨成品煤耗从改造前的250公斤降低到190公斤,全年减少煤耗3366吨,直接减少烟气排放1110万立方米,减少氮氧化物排放11吨。

第二,公司在二车间投资100万元,由沧州众诚环保公司建设脱硫、脱销、除尘一体化设备,于今年4月25日投入使用。

第三,公司投资90万元,由泊头得利隆环保设备公司建设两个车间SNCR

脱销系统。SNCR脱销工艺是减少氮氧化物排放的成熟技术。其工艺流程是20%的氨水经过计量泵稀释到需要的浓度,进入喷枪,用压缩空气雾化后喷入850-1000度的烟气中,在此温度区域,氨水与氮氧化物充分接触,反应生成氮气和水,然后经50米高的烟囱排放。此工艺没有废液和固体废物产生,没有二次污染,在国内外被广泛采用。此项目已经投入运行。

第四,保证一车间和二车间制瓶机冷却水循环使用。

第五,在原排水沟加装闸板,投资30万元新建厂区循环水系统。

第六,原煤气管道水封连续补水改为定时补水,不排放。

第七,保持空压机冷却水循环使用,不排放。 第八,修复公司通往污水处理厂的管道。

通过第四至第八项措施,一方面大大降低了消耗水量,生产用水实现零排放;另一方面,少量生活用水输送到污水处理厂。

附表5防治措施及治理效果

3.2. 环保污染防治投资估算 附表6

4. 初始排污权核算

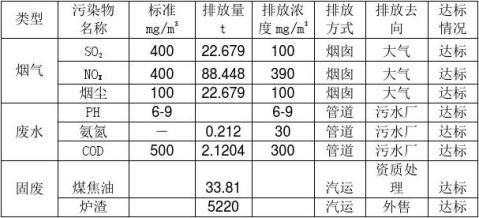

依据建设期环评,欧联公司两座窑炉烟气排放量23000万立方米每年,生活废水年排放量7068吨,煤焦油33.81吨,炉渣5220吨。烟气中的SO2和废水中的氨氮和COD均按实际检测值计算排放量,氮氧化物和烟尘按照达标排放值计算排放量。详见附表7。 附表7

5. 核算结论

根据以上分析和计算结果,结合建设期环评控制排污总量,申请下一持证周期

污染物排放总量控制指标: SO2:21.68t/年, NOX:90.7 t/年, 烟尘:22.679 t/年

氨氮:0.13 t/年, COD:0.99 t/年。

6. 附件

组织机构代码证书

工商营业执照

建设项目环评报告

建设项目环境保护设施竣工验收报告

第二篇:排污权初始分配

EnvironResourceEcon(2008)39:265–282

DOI10.1007/s10640-007-9125-4

ORIGINALPAPER

Theoptimalinitialallocationofpollutionpermits:

arelativeperformanceapproach

IanA.Mackenzie·NickHanley·TatianaKornienko

Received:24May2006/Accepted:30March2007/Publishedonline:3May2007

?SpringerScience+BusinessMediaB.V.2007

AbstractTheinitialallocationofpollutionpermitsisanimportantaspectofemissionstradingschemes.WegeneralizetheanalysisofB?hringerandLange(2005,EurEconRev49(8):2041–2055)toinitialallocationmechanismsthatarebasedoninter-?rmrelativeperformancecomparisons(includinggrandfatheringandauctions,aswellasnovelmecha-nisms).Weshowthatusing?rms’historicaloutputforallocatingpermitsisneveroptimalinadynamicpermitmarketsetting,whileusing?rms’historicalemissionsisoptimalonlyinclosedtradingsystemsandonlyforanarrowclassofallocationmechanisms.Instead,itispossibletoachievesocialoptimalitybyallocatingpermitsbasedonlyonanexternalfactor,whichisindependentofoutputandemissions.Wethenoutlinesuf?cientconditionsforasociallyoptimalrelativeperformancemechanism.

KeywordsRelativeperformance·Initialallocation·Pollutionpermits·Auctions·Rank-ordercontests

JELClassi?cationQ53·Q58·C72

1Introduction

Tradablepermitmarketshavebecomeanimportantpolicytoolinthecontrolofpollution.SchemessuchasRECLAIMandtheSO2marketintheUShaveshownthattradablepermitsareaviableandcosteffectivemarket-basedmechanism(e.g.Stavins1998;Schmalenseeetal.1998).Yetthereisstillanactivedebateabouthowtoallocatepermitendowmentsamongtheparticipating?rmsatthebeginningofeachtradingperiod.AsB?hringerandLange(2005)argue,someinitialallocationmechanismsmaycreateinter-temporaldistortionsandresultinsociallysuboptimaloutcomes.

I.A.Mackenzie(B)·N.Hanley·T.Kornienko

DepartmentofEconomics,UniversityofStirling,StirlingFK94LA,UK

e-mail:i.a.mackenzie@stir.ac.uk

123

266IanA.Mackenzieetal.Inthispaper,weextendtheresultsofB?hringerandLange(2005)toaccommodatemostoftheexistingdynamicinitialallocationmechanisms(includinggrandfatheringandauctions,aswellasnovelmechanisms).Weshowthatusing?rms’historicaloutputsforallocatingpermitsisneveroptimal,whileusing?rms’historicalemissionsisoptimalonlyinclosedtradingsystemsandonlyforanarrowclassofallocationmechanisms.Instead,itispossibletoachievesocialoptimalitybyallocatingpermitsbasedonlyonanexternalfactor,whichisindependentofoutputandemissions.Weoutlinesuf?cientconditionsforasociallyoptimalrelativeperformancemechanismanddiscusstheissuesrelatedtothechoiceofasuitablemechanismforinitialallocation.

Inouranalysis,wediscusstwotypesofmechanismsthatarecommonlyconsideredforallocatinginitialendowmentsofpermits.The?rstmechanism,whichwecallanAbsolutePerformanceMechanism(APM),involvespermitallocationsbasedonthelevelsofindivid-ual?rmactivity.Thesecondmechanism,whichwecallaRelativePerformanceMechanism(RPM),involvespermitallocationsbasedonhowthelevelsofa?rm’sactivitycomparetothelevelsofother?rms’activities,oroninter-?rmrelativecomparisons.Thedistinctionbetweenthesetwomechanismsiscrucialas?rms’behaviourinthepermitmarketissubjecttowhether?rms’believetheyareobtainingpermitsindividuallyor,asunderaRPM,aspartofagamewherea?rm’sallocationisdependentonother?rms’actions.Weshowinthispaperthatamechanismthatallocatespermitsbasedon?rms’absoluteperformance(APM),asusedbyB?hringerandLange(2005),isaspecialcaseofageneralizedrelativeperfor-mancemechanism(RPM),andthusthatthetwomechanismsshareanumberofoptimalitypropertiesinadynamicsetting.Wehoweverarguethatmechanismswhicharebasedonrelativeperformancemightbesuperioroverthosebasedonabsoluteperformanceandofferapromisingalternativetoauctioningandgrandfathering,namelyarank-ordercontest.

Bothtypesofmechanismshavehadimportantapplicationsinexistingtradablepermitmarkets.Absoluteperformancemechanismshavebeenadvocatedintheformofrelativeemissionsorintensity-basedemissionscaps(Fischer2001,2003;EllermanandWing2003;KuikandMulder2004;Pizer,2005;NewellandPizer,2006).1Insuchaschemeintra-?rmrelativecomparisonsexist,wheretheperformanceofagiven?rmisevaluatedrelativetoitsownactivity,butnotrelativetotheactivityofother?rms.Ratherthanhavingacaponabsolutelevelsofemissions,anintensity-basedcapinvolvesaceilingontheemissionsinten-sity(i.e.emissionsperoneunitofoutput).Thistypeofapproachisbecomingincreasinglycommon,forexample,Bode(2005)notesthatanumberofparticipantsintheUKemissionstradingschemeweregivenanintensitytarget.Furthermore,theBushadministrationintheU.S.hasstronglyadvocatedthistypeofapproachtotackleclimatechange(Kolstad2005;Pizer2005).Whenatradingsystemisbasedonemissionsintensity,each?rmcanunilaterallyincreaseboththeiroutputandemissionswithoutchangingemissionsintensityandwithoutanyeffectonother?rms(thepermitallocationisanadjustablegrandfatheringmechanism).However,themajorityofdistributionruleswhichhavebeendiscussedarerelativeper-formancemechanisms.ThetwomostcommonRPMsincludeauctions(where?rms’areallocatedpermitsbasedontheirrelativebids)andgrandfatheringwitha?xedcap(where?rms’areallocatedpermitsbasedontheirrelativeemissionslevelswithrespecttosome?xedcap)(seeHahnandNoll1982;Lyon1982;1986;Oehmke1987;MillimanandPrince1989;VanDyke1991;Franciosietal.1993;Parry1995;Parryetal.1999;CramtonandKerr2002).1Wemakeadistinctionbetweenintensity-basedcapsandoutput-basedallocation(althoughtheydobothactasanimplicitoutputsubsidy).Inintensityrate-basedmechanismstheemissioncapisadjustedtomaintainaconstantemissionsintensityandhenceallocationisnotdependentonother?rms’behaviour(e.g.thelevelsofother?rms’emissionsandoutputchoices).Incontrast,output-basedmechanismsaltertheaverageallocationperunitofoutputtomaintaina?xedemissionscap(allocationisdependenton?rms’behaviour).123

Theoptimalinitialallocationofpollutionpermits:arelativeperformanceapproach267However,thereisalargeselectionofRPMsthathavenotbeenextensivelyconsideredintheliterature.Forexample,yardstickcompetition,whereeach?rm’sperformanceisassessedrelativelytotheperformanceofother?rmshasbeensuggested(Shleifer1985;Franckxetal.2005;NalebuffandStiglitz1983a,b).Moreover,anovelRPMthatcouldbeenvisagedtoallocatepermitsistheuseofcontestsortournamentswhere?rmsspendresourcesinorderto‘win’aproportionofthepermitallocation(MoldovanuandSela2001,2006).

Inter-?rmcomparisonsusingrelativeperformancemechanismshaveanumberofgen-eralregulatoryadvantageswhichhavebeenwidelydocumentedintheliterature(LazearandRosen1981;Holmstr?m1982;GreenandStokey1983;NalebuffandStiglitz,1983a,b;Mookherjee1984;Shleifer1985;MoldovanuandSela2001,2006).Relativeperformancemechanismscanalsobeadvantageousinanenvironmentalcontext.Govindasamyetal.(1994)suggestedtheuseofatournamenttocontrolnon-pointpollution,andfoundthataRPMresultsinanumberofdesirableoutcomes.Franckxetal.(2005)extendedtheworkofGovindasamyetal.(1994)byusingadifferentRPM,yardstickcompetition,andconductedtheanalysisinamoregeneralenvironmentalregulatorysetting.They?ndthatthisRPMwillbedesirablewhenalargenumberof?rmsparticipateandcommonshocks(suchassimilartechnologyshocksoroilpricechanges)areexperiencedbyall?rms.

Ratherfewerauthorshavefocusedonrelativeperformanceissuesinemissionstrading.Usingarent-seekingmodel,MaluegandYates(2006)examinetheeffectsofcitizenpar-ticipationinapermitmarkettodeterminetheendowmentandpriceofpermits.They?ndthatcitizens’choiceoflobbyingandpermitpurchasesinamarketdependsontheinitialallocationmechanismchosen(auctioningorgrandfathering).Finally,GroenenbergandBlok(2002)outlineaninitialallocationmechanismforapermitmarketthatbasesdistributiononbenchmarkingtheproductionprocessofeach?rmand?nditeliminatesalargeamountofproblemsassociatedwithexistingallocationmechanisms.

Foranumberofdecadesthefreeallocation(grandfathering)ofpermitshasbeendiscussedasafeasiblemethodofallocation(e.g.Tietenberg1985).Indeed,themajorityofactualemis-sionstradingschemestodateusegrandfatheringastheprimaryallocationmechanismduetoitspoliticalviability:marketparticipantswillalwayslobbyforthefreeallocationofper-mits(Stavins1998).Grandfatheringmightalsobeseenasofferingacloser?ttoexistingregulatoryapproaches,sinceitdoesnotinvolveanyfundamentalchangeinpropertyrightscomparedwith,forinstance,asystemofperformancestandardsforpollutingemissions.Grandfatheringmightalsobepreferredbygovernmentsoncompetitiongrounds,sincetheavoidanceofalump-sumdistributionfromindustrytogovernmentcanavoiddisadvantagingdomestic?rmsrelativetotheirinternationalcompetitors.Onthenegativeside,grandfather-ingcouldbeseenasrewarding?rmswhohaveengagedinrelativelylowpollutioncontroleffortsinthepast.Asgrandfatheringisacommonlyusedtool,thediscussionsregardingtheeffectsofthemechanismhavebeenwidespread.Inparticular,RequateandUnold(2003)haveshownthatsubstantialinnovationincentivesexistfor?rmsinagrandfatheredemissionsscheme.However,Goulderetal.(1997)foundgrandfatheringtobearatherinef?cientallo-cationmechanismcomparedtoalternativeallocationprocedures.Recently,grandfatheringhasbeenadaptedtoincludeadynamicelement(Bode2006;B?hringerandLange2005).Inparticular,B?hringerandLange(2005)havediscussedupdatedgrandfatheringwhichcontinuallyupdatesthefreeallocationofpermitsbasedonhistoricalemissionsandoutput.2Theyfoundthatthedynamicallocationhastobecarefullyconsideredtoreducedistortionsintheproductandpermitmarket.

2SeeFischer(2001)forstaticanalysisofoutput-basedpermitallocations.

123

268IanA.Mackenzieetal.Anotherimportantaspectofthemechanismsinquestioninvolvesmulti-periodchoiceproblemsinpollutionpermitmarkets.Severalstudieshavefocusedongeneraldesigncon-siderationsformulti-periodpermitmarkets(CronshawandKruse1996;Rubin1996;KlingandRubin1997;Schennach2000;LeibyandRubin2001;YatesandCronshaw2001),yetonlyafewstudieshavefocusedontheinitialallocationofpermitsinthissetting.Inthecontextoftheelectricitysector,Bode(2006)?ndsconsiderablevariationinthedistributionalimpactsamongdifferentallocationmechanismswithinadynamicemissionstradingscheme.JensenandRasmussen(2000)modelanumberofallocationmechanismsinadynamicsettingand?ndthatwelfareandemploymentvarydrasticallyacrossallocationmechanisms.

TheworkwhichisthemostrelevanttoourpaperisbyB?hringerandLange(2005),whocomparetheef?ciencyofdynamicpermitallocationsbasedonoutput,emissionsandalump-sumtransfer.Incomparingef?ciency,theymakeadistinctionbetweenmarketsthatareopen(i.e.when?rmscantradeoutsidethedomesticmarket)andclosed(i.e.whenparticipating?rmscannottradeinpermitsoutsidethedomesticmarket).Thisdistinctionisimportanttopolicyanalysisastradablepermitmarketsarebecomingincreasinglyvariedinsizeandscopeandhavethepotentialtohaveeitheranopenorclosedmarketstructure.They?ndinaclosedmarketitisoptimaltoallocatepermitsoncriterianotrelatedtooutput,whereasforanopenmarket,anef?cientallocationoccurswhenthepermitsaredistributedusingalump-sumapproach.However,intheirtreatmentoftheinitialallocationmechanism,B?hringerandLange(2005)assumethatthepermitdistributiontoa?rmisbasedonlyon?rms’absolutelevelsofoutputandemissions,sothatother?rms’sactionsdonotaffecttheallocationofagiven?rm.Yet,giventhe?xedemissioncapconsideredbyB?hringerandLange(2005),thepermitallocationtoa?rmisalsocruciallydependentonthebehaviourofrival?rms.Thisisbecausea?xedemissionscapimpliesthatifinthecurrentperiodrival?rms,say,increasetheiroutputandemissionsrelativetoagiven?rm,thenthecurrent-periodaggregateoutputandemissionsincrease,thusdecreasingtheproportionoffuturepermitsthateach?rmcanreceivepereachunitofcurrentoutputandemissions.Astheresult,evenifagiven?rmdoesnotalteritsownchoices,itsownfutureallocationofpermitswillchange.ThuswearguethattheinitialallocationprocessconsideredbyB?hringerandLange(2005)shouldtakeintoaccountother?rms’actionsandthusshouldbemodelledasarelativeperformancemechanism.

OurpaperthereforeattemptstoextendB?hringerandLange(2005)byimplementingamoregeneraldesignofadynamicinitialallocationmechanism,whichallowsforthealloca-tionofpermitstobebasedoneach?rm’schoicesrelativetoother?rms.FollowingB?hringerandLange(2005),weconsiderallocationmechanismswhicharebasedonchoicesofoutputandemissions,butinadditionweconsiderpossiblepermitallocationsbasedonan“external”factorwhichisindependentofoutputandemissions.Thisallowsustocreateanencompass-ingmodelformostexistingtypesofinitialallocationmechanismssuchasgrandfathering,auctioningandcontests.WeshowthataRPMcanef?ciently(sociallyoptimally)allocatepollutionpermitsifthecriteriausedtocompare?rmsisbasedonsuchanexternalfactor,inacontest.Giventhevarietyofpotentialexternalfactors,wesuggestanumberofcriteriathataregulatormaytakeintoaccountwhenchoosingasuitablefactor.Wealsoargueinfavourofanewmechanism,whichinvolvesaninter-?rmcontestdesignedtoachievetwogoalssimultaneously—thatis,theprimarygoalofef?ciencyandsomesecondarygoal,suchasgeneratingrevenue,achievinghealthandsafetytargets,noisereduction,reductionofotherpollutants,etc.Giventhepoliticaleconomyproblemswithbothauctionsandgrandfatheringasawayofinitiallyallocatingpermits,thisnewmechanismmaywellbeofinteresttopolicymakers.

123

Theoptimalinitialallocationofpollutionpermits:arelativeperformanceapproach269Ourcontributionisthustwofold.First,weextendtheresultsofB?hringerandLange(2005)toawiderclassofmechanisms,so-calledrelativeperformancemechanisms,suchasgrandfatheringwith?xedcap,yardsticks,auctions,contests,etc.Althoughsuchmechanismscreateasituationwhere?rms’choicesareinterdependent,thegeneralintuitionofB?hringerandLange(2005)holdsintheNashequilibriumoftheensuinggame.Thatis,forawiderangeofmechanisms,fortheinitialallocationtobecost-ef?cient,itshouldnotdependon?rms’outputs,andmaydependon?rms’emissionsonlyinlimitedcircumstances.Second,weproposethatthelump-sumdistributionadvocatedbyB?hringerandLange(2005)canbeimplementedbetterwitharelativeperformancemechanismbasedonanexternalfactor.Suchacost–ef?cientmechanismallowstheregulatortoachieveasecondarytarget,suchasraisingrevenue,—thus“killingtwobirdswithonestone”.

Tothebestofourknowledge,thisisthe?rstpapertointroduceageneralisedRPMintoapermitmarketwhichallowsustomodelmostexistingrelative-basedmechanismsandhastheaddedadvantageofencompassingAPMs.Thepaperisorganisedasfollows:Sect.2outlinesourmodelandpresentsthesocialoptimalityconditionsand?rm’soptimisationproblem.Asociallyoptimaldynamicinitialallocationmechanism,whenthemarketexperiencesbothexogenousandendogenouspermitprices,isconsideredinSect.3.Section4discussestheexternalfactor,whileSect.5concludes.

2Themodel

WefollowB?hringerandLange(2005)andconsideramulti-periodpartialequilibriummodel.Thetechnologyofa?rmi(i=1,2,...,n)attimet(t=1,2,...)isgivenbyacostfunctioncit(eit,qit),whereqitisthe?rm’soutputlevel,andeitthe?rm’semissionsresultingfromproduction.Costscitareassumedtobetwicedifferentiableandconvex,with?2?22c2c2c2c2cc>0.it≤0,it>0,?e,?q,?itit≥0and?q·?e?ititititititThe?rmsellsitsoutputinacompetitiveproductmarketatapriceofpt.Finally,the?rmisregulatedbyacompetitiveemissions-tradingprogramandreceivesaninitialallocationofpermitsAit.

Wefurtherassumethateach?rmialso“produces”afactorzitwhichhasnodirectrele-vanceintheproductandemissionsmarket,andthusisoutsidetheregulator’sinterestsand/orjurisdiction.This“external”factoris“produced”byeach?rmindependentlyofoutputandvemissionsatacostvit(zit)(possiblyzero),withdit≥0.Whilethisexternalfactorisirrel-evanttotheproductandemissionsmarket,itmaydetermine?rms’permitallocationsAitinamannertobespeci?edlater.

2.1Thegeneralisedallocationmechanism

B?hringerandLange(2005)consideredamechanismwherebypollutionpermitsareallo-catedbasedonthelevelsof?rm’shistoricalproductionqitandemissionseit.3We?rstextendthismechanismbyassumingthatinadditiontooutputandemissions,some“external”factormayplayaroleinhowmanypermitswillbeallocatedtoagiven?rm,butthisfactorhasnorelevancetotheproductandemissionsmarket,andthusisbeyondtheinterestorjurisdiction3B?hringerandLange(2005)consideredanumberofhistoricalobservationperiods,l=(1,2...,s).Forexpositionalsimplicity,werestrictourmodeltol=1(thehistoricalperiodissimplythepreviousperiod).Itisstraightforwardtogeneraliseourmodeltol>1historicalobservationperiods.

123

270IanA.Mackenzieetal.oftheregulator(anditisthisfactorwhichdeterminesthelump-sumallocationsinthemodelofB?hringerandLange2005).

Examplesofapossibleexternalfactorincludepopulationsizeina?rm’slocality,a?rm’ssociallyresponsibleactivities,a?rm’semissionsofotherpollutants,arandomeventsuchalotterydrawandsoon.Wedenotesuchexternalfactorsaszit.WhilewewilldiscusstheexternalfactormoreinSect.4,itisworthnotingherethatthenatureoftheexternalfactordeterminesboththecostofthisfactortothe?rm,aswellasthedegreeof?rm’scontroloverthisfactor.Forexample,populationsizeisbothbeyondthe?rm’scontrolanditis“free”tothe?rm.Ontheotherhand,lotteryticketscanbeboughtby?rms,orcanbeallocatedto?rmsbytheregulator(andthusarebeyond?rms’control).Incontrast,inapermitauction,bothsuccessandcostsofeach?rm’sbiddependsonthebidsofotherparticipating?rms.Thus,theallocationmechanismbasedonabsoluteperformance(APM)isgivenby

t?1?t?11?APMAit=λq?(ei(t?1))+λtz?,ith(qi(t?1))+λe,itg,itf(zi(t?1))(1)

1λtz?,it≥0aretheweights(inperiodt)placedonperiodt?1’sperformance.Theweightsre?ecttherelativeimportanceofaparticularactivity,andcanvaryacrosstimeperiodsandacross?rms.

WeextendEq.1byallowingfor?rms’performancetobeevaluatedincomparisontoother?rms,i.e.howagiven?rmi’sperformanceattimetinproductionqit,emissionseit,anexter-nalfactorzitcomparesrelativelytotheperformanceofeveryother?rm?i={1,...,i?1,i+1,...,n}.Formally,?rmi’sperformanceattimetinoutputrelativelytoother?rms’outputq?itisgivenbyarelativeperformancefunctionh=h(qi(t?1),q?i(t?1)).Similarly,relativeperformanceinemissionsandexternalfactoraregivenbyg=g(ei(t?1),e?i(t?1)),andf=f(zi(t?1),z?i(t?1)),respectively.Weassumehi=,gi=,fi=it>0ititsothat,forgivenlevelsofother?rms’performance,higherlevelsofemissions,output,andtheexternalfactorresultinalargerpermitallocation.Wealsoassumethath?i=,?itt?1t?1?,gwhereh?,f?areincreasingandcontinuouslydifferentiablefunctions,andλq,it,λe,it,?g?f,f?i=≤0,sothatforagivenlevelof?rm’sperformance,itsallocationg?i=?it?itdoesnotincreasesifother?rms’increasetheirlevelsofemissions,output,ortheexternal

factor.4

Wetakearathergeneralviewoftherelativeallocationfunctions.Thatis,toallowforuncer-taintyoverallocations,wetreatthesefunctionsasexpectationsoverpossiblerealisations.Thusallocationscanbedistributedusingdeterministicrules(suchasyardstickcompetitions)devisedbytheregulator,aswellasbylotteries,auctions,orcontests.Foranalyticaltractabil-ity,weassumethattherelativeallocationfunctionsh,g,farecontinuouslydifferentiable.5Forexample,a?rm’srelativeallocationcanbedeterminedcontinuouslybasedonhowitsqitownoutputcomparestoaggregateoutput,e.g.h(qi(t?1),q?i(t?1))=α.Anotherit?i?itexampleofacontinuousrelativeallocationfunctionincludesTullock-type(winnertakesall)contestallocations,wherea?rm’sexpectedamountofpermitsisgivenbyallparticipating

qr?rms’outputsasfollows:h(qi(t?1),q?i(t?1))=β—i.e.thesizeofthepermit?i?ititlotβmultipliedbytheprobabilityofwinningthecontest(seeSkaperdas1996).

4Instead,onecanassumethathandgarenegative.ii

5Ourargumentwillnotchangeifwerelaxtheassumptionofcontinuitytoincluderelativeperformancemechanismssuchaswinner-payandall-payauctionsinvolvingdiscontinuitiesin?rms’payofffunctions.Todealwithsuchdiscontinuities,onetypicallyassumesthatall?rmsfacecommonlyknowncontinuouslydiffer-entiabledistributionof?rms’“types”,andthatall?rmsfollowsymmetricstrictlyincreasinganddifferentiablestrategy,sothateach?rm’sexpectedpayofffunctionbecomescontinuouslydifferentiable.

123

Theoptimalinitialallocationofpollutionpermits:arelativeperformanceapproach271Thus,thepermitallocationfor?rmiattimet,accordingtothegeneralizedRelativePerformanceMechanismis

t?1t?1t?1RPMAit=λq,ith(qi(t?1),q?i(t?1))+λe,itg(ei(t?1),e?i(t?1))+λz,itf(zi(t?1),z?i(t?1))(2)

Comparingthisrelativeperformanceallocationmechanismtothatbasedonabsoluteper-formance(1),onecanobservethefollowing:

Remark1Ifh?i≡g?i≡f?i≡0thenarelativeperformanceallocationmechanismreducestoanabsoluteperformanceallocationmechanism.

Inotherwords,theabsoluteperformancemechanismconsideredbyB?hringerandLange(2005)isaspecialcaseofrelativeperformancemechanismwhen?rmi’sallocationisinde-pendentoftheremaining?rms’actions.Inthiscase,theremaining?rms’actionshavenoimpacton?rmi’sallocation,anda?rmicanobtainpermitsbyoptimallychoosingqit,eitandzit,withoutconsideringother?rms’actions.

NotethatB?hringerandLange(2005)implicitlyassumethatthegrandfatheringmecha-nismisanabsoluteperformancemechanism.However,witha?xedemissioncap,foragivenbehaviourofother?rms,ifaparticular?rmincreases/decreasesitsoutputand/oremissions,thatwouldaffecttheaggregateoutputandemissionsofdomestic?rms,ultimatelyaffectinghowmanypermitsboththat?rmandallother?rmswillreceive.Thus,itisimplicitinB?hrin-gerandLange(2005)thatthefactorweightswillchangeeachperiodtore?ectchangesin?tistheaggregateactivities.Toseethis,supposethatattimeta?xedamountofpermitsEallocatedamongn?rmsproportionallytoeach?rm’soutputqit.Inotherwords,each?rm?tE.Thus,theoutputweightγthastobeireceivesanallocationγtqit,whereγt=it?i?itadjustedeachperiodtore?ectchangesinaggregateproduction.Itiseasytoseethatsuchaq?t?xedcapgrandfatheringmechanismisaRPMwithh(qi(t?1),q?i(t?1))=E.it?i?itWhenarelativeperformancemechanismisused,?rmi’schoicesaffectthenumberofpermitsallocatedto?rmj=i,andthusaffect?rmj’spro?ts,andviceversa.Inotherwords,aRPMcreatesasituationwhere?rmschoicesareinterdependent.Insuchasitua-tion,arational?rmwillmakeitschoicesstrategically,bytakingintoaccounttheanticipatedactionsofitsrivals.Therelativeperformancepermitallocationmechanismthusresultsinagameamongparticipating?rms,whichleads?rms’behaviourtobetypicallydifferentfromtheirbehaviourwhenfacedwithanAPM.Toexplorethedistortionaryeffectofsuchbehaviour,we?rstneedtoconsiderthesociallyoptimalsituation.

2.2Thesociallyoptimaloutcome

Wenowconsidertheregulator’spointofview.FollowingB?hringerandLange(2005)weassumethattheregulatorcaresaboutpro?tsandcostsassociatedwiththeproductionofoutputandemissionsofthespeci?cpollutant,aswellasthetradeinthepollutionpermits,butisnotinterestedintheexternalfactorssuchaspopulationsize,lotterydraws,orauctionbids(wewillcomebacktothisassumptioninSect.4).Thus,theregulator’sobjectiveistomaximise(minimise)theaggregatepro?t(cost)thatallthedomestic?rmsincurwhileproducingtheproductoftheregulator’sinterestsorjurisdictionwhilstbeingconstrainedbytheemissionsprogram.

Whentradeinemissionspermitsisnotrestrictedtotheregulator’sjurisdiction,?rmscanimport/exportemissionsacrossthesystem’sborders.Fromaregulator’spointofview,thisisa(small)openemissionstradingsystem,wherethepermitpriceisexogenouslydeter-mined,andtheaggregateemissionsinthejurisdictionarenotcapped.Thismayoccurwhen

123

272IanA.Mackenzieetal.themarketisopentotransactionsfromother(possiblylarger)schemes.Forexample,intheEuropeanUnionEmissionsTradingScheme(EU-ETS),memberstatesallocatepermitsdomestically,but?rmsineachmemberstatecantradepermitswith?rmsinothermemberstates.

Insuchasystem,theregulator’sobjectivetakesintoaccountthebalanceofthetradeintheemissionpermits.Thus,giventhesetofprices(σt,pit),theregulator’sobjectiveisto

?n?n?????Maxpitqit?cit(eit,qit)?σteit?t(3)qit,eitti=1i=1

whereσtistheexogenouspermitpricedeterminedbythe(international)demandandsupplyofpermitsintheopenmarketandtisthedomesticemissionscapattimet.Foreach?rmiandeachofit’srival?i={1,...,i?1,i+1,...,n},thesociallyoptimalconditionsareasfollows:6

pit=

??citit(4)(5)?cjt?cit=?(=σt)itjt

foralli,j=i,t.Thatis,atperiodtall?rmswillsimultaneouslyequatetheirmarginalproductioncoststotheir?rm-speci?cproductprice(4).Also,intheequilibrium,?rms’mar-ginalabatementcostswillbeequalized(5),andwillbeequaltothe(exogenouslydetermined)commonpermitprice.

Incontrast,inaclosedemissionstradingsystem,asingleregulatordistributes?thetotalsupplyofpermits,andthusensuresthattheaggregateemissionsarecapped:ieit=t.Theemissionspermitpriceisendogenouslydeterminedbythe(domestic)demandandsupplyintheclosedmarket.Theregulatorsobjectivefunctionisthus:

??nn???Maxpitqit?cit(eit,qit)subjecttoeit=t(6)qit,eitti=1i=1

Thesociallyoptimalconditionsareidenticaltotheconditions(4–5),exceptthat?rms’mar-ginalabatementcostswillbeequaltotheshadowpriceofabatement.

2.3Firmoptimisation

We?rstextendedtheallocationmodelofB?hringerandLange(2005)byallowingforeval-uationsbasedonanindependentexternalfactorsuchaspopulationsize,sociallyresponsibleactivities,emissionsofotherpollutants,lotterydraw,andsoon.Wenowfocusouratten-tiononthe?rm-speci?cproblem.Giventhepro?leofother?rms’actions,thesetofprices(σt,pit),anditspermitallocationAitforthetargetpollutant,a?rmiwillchoosealevelof?,e?,z?)tomaximiseitstotalstreamofpro?ts:emissions,outputandanexternalfactor,(qit,it,it

qit,eit,zitMax?[pitqit?cit(eit,qit)?vit(zit)]?σt(eit?Ait)t=1

6WefollowthelanguageofB?hringerandLange(2005)andrefertotheleast-costoutcomeandcorrespondingconditionsassociallyoptimal.

123

Theoptimalinitialallocationofpollutionpermits:arelativeperformanceapproach273Thus,whenarelativeperformancemechanism(2)isusedtoallocatepollutionpermits,?rmi’sobjectivefunctionis:??Max[pitqit?cit(eit,qit)?vit(zit)]?σteitqit,eit,zitt=1

t?1t?1+σt[λq,ith(qi(t?1),q?i(t?1))+λe,itg(ei(t?1),e?i(t?1))?t?1+λz,itf(zi(t?1),z?i(t?1))]]

Foreach?rmianditsrivals?i={1,...,i?1,i+1,...,n},theoptimalchoicesaredeterminedbythe?rstorderconditionsasfollows:

tpit+σt+1λq,i(t+1)hi(qit,q?it)=?c

it

?c

it(7)(8)

(9)σt?σt+1λte,i(t+1)gi(eit,e?it)=?σt+1λtz,i(t+1)fi(zit,z?it)=dv

dzit

SimilarlytotheabsoluteperformanceallocationmechanismofB?hringerandLange(2005),whena?rm’scurrentoutputandemissionsdetermineitsfutureallocationofpermits(andthusitspro?ts),each?rmwilltakethisintertemporaleffectintoaccount.7Thus,relativetothesociallyoptimalconditions(4)and(5),amechanismwhichusespastperformanceinoutputandemissionswillgenerateanintertemporaldistortionof?rms’incentives.

Importantly,thisholdsbothfortheabsoluteperformancemechanism(1)butalsofortherelativeperformancemechanism(2).Toseethat,compareequations(7)to(4),aswellas(8)to(5).Giventhatgiandhiarebothpositive,suchamechanismcreatesanimplicitincentivetoincreaseproductionandemissionsbeyondsociallyoptimallevels.8Becausetheexternalfactorzisoutsidetheinterestsorjurisdictionofthesocialplanner,itdoesnotdistortincen-tiveswheneitherarelativeorabsoluteperformancemechanismisused(9).Foragivenpro?le?,optimally,sothatthemarginalcostofother?rms’actions,?rmichoosesexternalfactorzitofobtainingthefactorequalsthemarginalfuturebene?tobtainedfromthepermitallocation.Insummary,wehavethefollowinggeneralizationoftheintuitionofB?hringerandLange(2005):

Remark2When?rms’permitallocationsareatleastpartiallydeterminedbyoutputandemissions,allpermitallocationmechanismsofthegeneralform(2)createdistortionaryincentivesintheproductandpermitmarkets.

Aswenotedabove,theabsoluteperformancemechanism(1)isaspecialcaseoftherelativeperformancemechanism(2).Thus,anymechanismthatallocatespermitsbasedonhistoricaloutputand/oremissionswilldistort?rm’sincentivestoproduceoutputandemis-sionsoptimally.Notonlywouldthedistortionsoccurwhentheadjustablecapgrandfatheringscheme(whichisanAPM)isused,butalsoanyotherschemewhichutilizes?rms’relativeperformancewithrespecttoeachotherinoutputand/oremissions.

7Moreover,thelongerhistoricalperiodoverwhich?rm’shistoricalrelativeperformanceinoutputandemis-sionsistakenintoaccountbytheschemedesigners,themoreimportantistheeffectofeachcurrentchoiceonfutureallocations.Becauseweassumethatonlyonepreviousperiodaffectscurrentallocation,wedonotexplicitlyaddressthispointhere.

8Similarly,ifeitherorbothgandharenegative,therewouldbeanincentivetodecreaseeitherproductioniioremissionsorbothtoasuboptimallevel.

123

274IanA.Mackenzieetal.Thisproblem,ofincreasedoutputandemissions,isassociatedwiththe“ratcheteffect”—usingcurrentperformancetodeterminefuturetargetsandfutureinitialallocations(Weitzman1980;Freixasetal.1985;Berglandetal.2002).Ifa?rmdecidednottoincreaseemissions(output)thentheirpermitallocationwouldbe“ratcheted”down,astheiremissions(output)wouldberelativelylowerthanallother?rms.Ifsuchasystemwasimplemented,?rmsthatactivelyloweredemissions(output)wouldbeimplicitlypunished.Therefore,each?rmhasanincentivetoincreaseitsrelativeemissions(output)tostoptheirfuturepermitallocationfrombeinglowered.Thus,bothRPMsandAPMswillcreatedistortionsintheoutputandpermitsmarketwhenthecriteriausedtoallocatepermitsisbasedonhistoricaloutputand/oremissionsinformation.

However,RPMspossessanadditionalimportantfeaturethatAPMsdonot,namely,thataRPMresultsinagameamongparticipating?rms.Thisisbecausewheneach?rmisevalu-atedrelativelytoother?rms,?rms’actionsbecomeinterdependent.IntheNashequilibrium?,e?,z?)accordingtoEquats.7–9giventheofthisgame,each?rmchoosesapro?le(qitititequilibriumbeliefsaboutother?rms’choices.

3Sociallyoptimalallocationmechanisms

Inthelastsectionweexaminedtheinef?cienciescausedbyageneralisedrelativeperfor-mancemechanismwherethecriteriausedtoallocatepermitswerebasedonhistoricaloutput,emissions,andanexternalfactor.InthissectionwewillextendtheargumentofB?hringerandLange(2005)againsttheuseofhistoricaloutputsingeneralizedrelativeperformancemechanisms.Moreover,whenthesystemisopen,sothatthepermitpriceisdeterminedexog-enously,theexternalfactorshouldbethesoledeterminantofthe?rm’sallocations.Whentheclosedsystemisused,wherethepermitpricecanendogenouslyadjusttotheaggregatesupplyofemissions,thereisapossibilityofusingalinearperformanceschemeinemissions.

3.1Opensystem

Recallthatina(small)openpermittradingsystem,theaggregatesupplyofpermitsisdeter-minedjointlybythedomesticallocationofpermitsandbytheallocationsofpermitstoallotherforeignparticipants.Thus,thepermitpriceisdeterminedexogenously.FollowingB?hringerandLange(2005),themarketequilibriumoutcome(8),canbetransformedintothesociallyoptimaloutcome(5),byimplementingthesuf?cientconditionλte,i(t+1)=0foralli.Similarly,onecanensurethattheindividuallyoptimalproductionlevel(7)correspondsttothesociallyoptimalproductionlevel(4),bysettingλq,i(t+1)=0foralli.Thisleadsustothefollowing:

Proposition1Ina(small)opentradingsystem,asociallyoptimaloutcomecanbeachievedbyallocatingpermitsbasedonrelativeperformanceinanexternalfactorzitonly.Thatis,ant?1t?1optimalmechanisminvolvessettingλq,it≡λe,it≡0,foralli,tintheallocationequation

(2):

1Ait=λtz?,itf(zi(t?1),z?i(t?1))(10)

Thatis,inopentradingsystems,toachievethesociallyoptimaloutcome,aregulatorshouldplaceazeroweightforhistoricaloutputandemissions,anddesignasystemthatisbasedsolelyon?rms’performanceinanexternalfactor,whichisnotrelatedtotheoutputandemissionschoicevariables.Byrestrictingallocationtovariablesthatdonotaffectthepermit123

Theoptimalinitialallocationofpollutionpermits:arelativeperformanceapproach275andproductmarket,the?rms’incentivesremainundistorted.Thisoccursbecauseusinganexternalfactorbreakstheintertemporallinkbetweenthepermitrent(outputsubsidy)andtheincentivetoalterthechoicevariables.Ourresultsagreewiththecommonlyheldviewthatonecanobtainasociallyoptimaloutcomebydistributingpermitsbasedonanexternalfactor(Goulderetal.1997;CramtonandKerr2002).Becauseanabsoluteperformancemechanismisaspecialcaseofrelativeperformancemechanism,theaboveresultcanbereducedtotheresultofB?hringerandLange(2005,Proposition2).Thatis,iftheallocationfunctionforeach?rmiisindependentofrivals’actions,itissociallyoptimaltousehistoricalexternalfactortoallocatepermits.

3.2Closedsystem

Wenowconsideranemissionsprogramwherethepermitpriceisendogenouslydeterminedbythedemandandsupplyinaclosedpermitmarket.Thisincludesaconventionalclosedmarketsystemwherethesolesupplyofpermitsoriginatesfromoneregulatorandwherethepermitpriceisdeterminedbytheaggregatelevelofemissionsintheemissionsprogram.Comparingequations(4)with(7)andequations(5)with(8)onecanobtainthefollowingsociallyoptimalconditionsforoutputandemissions:

tλq,i(t+1)hi(qit,q?it)=0

tλte,i(t+1)gi(eit,e?it)=λe,j(t+1)gj(ejt,e?jt)(11)(12)

?i,j=iand?i={1,...,i?1,i+1,...,n}.

Similartotheexogenouscase,Eq.11suggeststhattoachievesocialoptimality,themar-ginalbene?tto?rmifromincreasingoutputshouldbeequaltozero.Thus,asuf?cientconditionforachievingsocialoptimuminvolvestheregulatorplacingazeroweightoneach?rm’shistoricaloutput:

tλq,i(t+1)=0?i,t(13)

Incontrast,Eq.12suggeststhatthemarginalpermitallocationshouldbeequalacross?rms.Thisconditionisdif?culttoensureforall?rmsandforallfunctionalformsofg.Wecould?ndonlyonesetofsuf?cientconditionsforsocialoptimalityinemissionswhichholdsforallfunctionalformsofg,whichissimilartothesuf?cientconditionsforoutput:

λte,i(t+1)=0?i,t(14)

thatis,theregulatorshouldputazeroweightoneach?rm’shistoricalemissionschoices.Theseconditionsnotonlyensuresocialoptimalityforanyrelative(andthusabsolute)perfor-mancemechanism,butalsorequireslessproblemsolvingbytheregulatorandparticipating?rms.

Instead,ifanon-zeroweightforhistoricalemissionschoicesisselectedthenonlyanarrowclassofRPMssatisfythesocialoptimalitycondition(12).Inotherwords,onlyRPMsthatcreateanidenticalmarginalallocationcanobtainasociallyoptimaloutcome.Anexampleofsuchmechanismisayardstickmechanismthatallocatespermitstoeach?rmbasedonhowitshistoricalemissionscomparetheother???to????rms’averagehistoricalemissionse.g.

eEt+1?itg(eit,e?it)=1foralliandt(aswellasits“absolute”+αteit?counterpartg(eit)=e,i(t+1)

makestheproblemeasier.αteit).Obviously,equatingemissions“weights”λe,ite,i(t+1)across?rms

123

276IanA.Mackenzieetal.Thus,anyRPMwithidenticalmarginalallocationsacross?rmscansociallyoptimallyallocatepermitsbasedon?rms’relativeperformanceswithrespecttohistoricalemissionsandanexternalfactor.OurresultsagreewithB?hringerandLange(2005)whowereabletoprovethattheoptimalityresultholdsforalinearAPM.Therefore,RPMsandAPMsthathaveidenticalmarginalallocationsacross?rmscanobtainasociallyoptimaloutcome.Thus,itfollowsfrominspectionofequations(11)and(12)that:

Proposition2Inclosedtradingsystem,asociallyoptimaloutcomecanbeachievedbyallocatingpermitsbasedonrelativeperformanceinanexternalfactorzitaswellasusingsuitablychosenrelativeperformanceschemesinhistoricalemissions,andignoring?rms’t?1historicaloutputs,i.e.λq,it≡0,foralli,t.Thus,theallocationequation(2)becomes:

???1?t?1?Ait=λtge,efz,z+λi(t?1)?i(t?1)i(t?1)?i(t?1)e,itz,it

wherefunctionsgarechosensuchthatcondition(12)issatis?ed.

Again,becauseabsoluteperformancemechanismsareaspecialcaseofrelativeperfor-mancemechanism,theaboveresultcanbereducedtotheresultofB?hringerandLange(2005,Proposition1).Importantly,onecanachievesocialoptimalityintheclosedsystembyusingthesamepermitallocationschemeasintheopensystem:

Corollary1Inclosedtradingsystem,asociallyoptimaloutcomecanbeachievedbyallocat-t?1t?1ingpermitsbasedonrelativeperformanceinanexternalfactorzitonly,i.e.λq,it≡λe,it≡0,foralli,t.Thus,theallocationequation(2)becomes:

1Ait=λtz?,itf(zi(t?1),z?i(t?1))(15)(16)

Inotherwords,regardlessofthenaturetradingsystem,onecanimplementthesociallyoptimalpermitallocationmechanismbasedontherelativeperformanceintheexternalfactor.Thus,theexternalfactorplaysakeyroleinoptimalpermitallocationscheme,callingforfurtherissuestobeconsideredbytheallocationmechanismdesigner.

4Theexternalfactor

Wearguedintheprevioussectionthatonecanachievesocialoptimalityintheproductandtargetpollutantmarketsbyusing?rms’relativeperformancewithrespecttoanexternalfac-tortoallocatetargetpollutionpermits.Inthissection,wewilldescribetheexternalfactor,possiblemechanismsbasedonrelativeperformanceinthisexternalfactor,aswellasthebene?tsofthisapproach.

4.1Criteriaforthechoiceofanexternalfactor

Wede?netheexternalfactorasanythingwhichhasnodirectrelevancetotheproductandtargetpollutantemissionsmarkets,andwhichisthusbeyondtheinterestorjurisdictionoftheregulator.Examplesofpossibleexternalfactorincludepopulationsizein?rm’slocality,?rm’ssociallyresponsibleactivities,?rm’semissionsofotherpollutants,arandomeventsuchalotterydraw,andsoon.Sincetheexternalfactorcantakeavarietyofforms,theregu-latorfacesachoiceofasuitableexternalfactor.However,thereisnumberofissuesinvolvedintheexternalfactorchoice.

123

Theoptimalinitialallocationofpollutionpermits:arelativeperformanceapproach277Independence:Toachievesocialoptimality,the“production”oftheexternalfactorhastobeindependentof?rms’outputandemissionsofthetargetpollutant.Obviously,iftheexternalfactoriscorrelatedwith?rm’soutputand/oremissions,?rms’incentiveswillbedistorted,andsocialoptimalitywillnotbeachieved.

Easeofuse:Asthemainobjectiveoftheregulatoristominimisetheaggregatecostoftheemissionsprogram,adesirableexternalfactorshouldbeeasyfortheregulatortoobserve.RewardofEffort:Theregulatormaychoosetheexternalfactortoreward?rms’efforts.Whenheterogeneityof?rms’issubstantial,theexternalfactormaytakeaformof“inten-sity”,orwithin-?rmrelativeassessment—forexample,proportionof?rm’scommunityactivitiesrelativelytothesizeoflocality.

EqualOpportunity:Theregulatormaywishtoensurethatall?rmshaveequalopportunitytoobtainpermitallocations,andthusthattheexternalfactorcanbeproducedbyeveryparticipating?rm.Whentheregulated?rmsbelievetheyarebeingtreated“fairly”inasenseofequalityofopportunity,thentheemissionsprogrammayhaveahigherchanceofsuccess.

PoliticalAcceptabilityoftheExternalFactor:Thesuccessoftheallocationschememaydependonpoliticalacceptabilityoftheexternalfactorbytheregulated?rmsandregulator(aswellaspossiblybythegeneralpublic).

FairAllocations:Aspsychologistssuggest,judgmentsofallocativefairnessareaffectedbytherelativemeritsoftherecipients,thussuggestingthatrelativeperformancemech-anismsmaybeperceivedtobe“fair”aslongastheexternalfactorisconsideredtobemeritorious.9

DoubleDividend:Ofparticularinterestmaybethoseexternalfactorswherethemarginalbene?tswilltypicallyexceedthemarginalsocialcosts.Inotherwords,theexternalfactormaybechosensothatitconferssomeadditionalbene?ttotheregulatorotherthanthecontrolofemissions.Theregulatorcouldde?neacostlyzitinsuchawayasitwouldprefertoobservehigher(orlower)values.

Asthelastthreeoftheseissuesmaybeofparticularinteresttomechanismdesigners,wewilldiscussthemindetail.

4.2Anon-monetaryexternalfactor

Asitwasmentionedabove,oneofthepossiblereasonswhyregulatorsavoidallocatingper-mitsbasedon?rmsperformanceinexternal“monetary”factor—suchasauctionbids—isthatitispoliticallyunpopular.Wethussuggestthatperhapsamechanismthatisbasedonrelativeperformanceinanon-monetaryexternalfactor,mayhaveabetterpoliticalaccept-ability,inparticulariftheyinvolveapossibilityofsocialbetterment.Whenanon-monetaryexternalfactorischosenasabasisforpermitallocations,therearenodirect?nancialtrans-fers.Firmsinsteadarerewardedforthe(non-monetary)actionstheychoose.Thisreasoningisverysimilartotheargumentsthatadvocateagrandfatheringsystemratherthananauction(Stavins1998).However,asweshowedabove,grandfatheringschemesinvolvinghistoricallyupdatedoutputsandemissionsaredistortive.Yetwesuggestthataregulatorcanchooseanon-monetaryexternalfactorthatisagreeablefor?rms(oratleastlesscontroversialthanothercriteria).

9Notefurtherthat,asMellers(1982,1986)demonstrated,theallocations(ofsalariesandtaxes)judgedtobe“fair”byhumansubjects,dependedontherankofeachrecipient’smeritinthemeritdistributionofthecom-parisongroup.Inotherwords,arank-basedcontestmaybeagoodcandidatefora“fair”relativeperformancemechanism.

123

278IanA.Mackenzieetal.Thereisavarietyofpossiblenon-monetaryexternalfactors.Charitableactivitiessuchassupportofimprovementsineducationandhealthinfrastructureinthelocalcommunitymaybeviable.Thismayprovetobeameritoriousallocationprocess;?rmsaregiventhe“right”topollutebasedonthedegreeoftheirsocialresponsibilitieswithinacommunity.Anothersetofalternativeexternalfactorsmaybeofparticularrelevancetoenvironmentalregulator.Thesemayincludereductionofanexternal“basket”ofenvironmentalpollutantsorenvironmentalindicators,forexamplenoisepollution,orinvestmentsinenergyef?ciency.Thatis,?rmscouldbeallocatedpermitsforthetargetpollutantbasedontheirreductionofcompletelyseparateandindependentpollutants.

However,wehavetoemphasizeagainthat,toachievesocialoptimalityinoutputandemissionsmarkets,apotentialnon-monetaryexternalfactorzithastobeindependentfromthe?rm’semissionsandoutputchoices.Thusspecialcarehastobetakeninregulator’schoiceofnon-targetpollutantsasexternalfactorsasemissionsofsomepollutantscanbecorrelatedwithemissionsofthetargetpollutant,leadingtopotentialinef?cienciesintargetpollutantemissionsmarket.

4.3Theregulator’ssecondaryobjective

Aswementionedabove,theremayexistexternalfactorswhichareirrelevanttotheproductandtargetpollutantemissionsmarket,butneverthelesstheregulatormaybeinterestedin?rmsengaginginproductionofthisexternalfactor.Ifthisisthecase,theregulatormayhaveaprimaryobjectiveofcontrollingemissionsatlowestsocialcost,aswellasasecondaryobjectiveofincreasingtheaggregateamountoftheexternalfactor,oritsnetbene?ts.

Oneobviousexampleofmultipleregulatoryobjectivesisthe“doubledividend”argumentfortheuseofauctionsforpermitallocations.AsCramtonandKerr(2002,p.335)suggest,apermitauctioncanraiserevenuewhilstenforcingemissionscontrol.Thisrevenuecanbeusedtoreducedistortionarytaxesintheeconomy(e.g.Parry1997)orreducetheburdenonauctionparticipantsthrougharevenueneutralauction(HahnandNoll1982;Hahn1988).Alternatively,therecanbetwo(non-competing)regulatorswithdifferentobjectives.Forexample,theenergy(electricity)industrymayberequiredtoparticipateinanemissionsprogramwhilstsimultaneouslybeingoverseenbysocial/publicpolicyregulatortopromote?rms’anti-discriminatorypersonnelpolicies.Theenvironmentalpolicyregulatoraimstocontrolaggregateemissionsatthelowestpossiblecostandisnotconcernedaboutthesizeorcostoftheexternalfactorinanyway.Thesecondregulatorispossiblyasocial/publicpolicyregulatorwho’saimistomaximisetheaggregateexternalfactorproducedbytheparticipating?rms.Anotherexampleofadoubleobjectivemaybetheregulationoftwoenvironmentaltargets,withonetargetbeingcontrolledbytargetpollutantpermitmarket,andanothertargetcurrentlybeingunregulated—forexample,emissionsofCO2andabasketofothergreenhousegases.Inanycase,thesecondaryobjectiveinvolvesmaximizationof?rms’aggregateactivities,expenditures,orefforts(forasimilarobjectiveseeforexampleMoldovanuandSela2001).

Aswearguedabove,onecanachievethesociallyoptimaloutcomeinproductandtar-getpollutantmarketsbyallocatingpermitsusinganexternalfactoronly.Therefore,usingsuchanapproachsimultaneouslyachievestheprimarytargetofsociallyoptimaloutcomeinthetwomarketsandasecondarytargetofmaximisationoftheaggregateexternalfactor.Formally,let?∈(0,1]representtherelativeimportanceoftheprimarytarget(emissionscontrol),andletusconsider(small)opensystem(theargumentfortheclosedsystemwillbeonlyslightlydifferent).Inthiscase,the“combined”regulatoryobjectiveis:

123

Theoptimalinitialallocationofpollutionpermits:arelativeperformanceapproach

n??

ti=1n?i=1279qit,eit,zitMax[?(pitqit?cit(eit,qit))?(1??)zit]subjecttoeit=t(17)

The?rstorderconditionsforemissionsandoutputareidenticaltothesociallyoptimalequations(4)and(5).Moreover,thiscombinedregulatoryobjectiveallowsfor?rms’indi-viduallyoptimalchoiceoftheexternalfactor.ItfollowsfrominspectionofEqs.7–9and17that:

Remark3IfaRPMisusedtoallocatepermitsbasedonacostlyexternalfactorthenasec-ondary(regulatory)targetcanbeachievedwhilststillachievingthesociallyoptimaloutcomewithrespecttothetargetpollutant.

Inotherwords,byallocatingtargetpollutantpermitsamong?rmsbasedontheirrelativeperformanceinasuitablychosenexternalfactor,aregulatorcan“killtwobirdswithonestone”byachievingemissioncontrolatthelowestsocialcostinoutputandpermitmarkets,andmaximizingaggregateproductionofasociallybene?cialexternalfactor.

5Conclusion

Thepurposeofthispaperwastoanalysetheimpactandoptimalityofimplementingagen-eralised(dynamic)relativeperformancemechanismfortheinitialallocationofpollutionpermits.WeextendtheresultsofB?hringerandLange(2005)toaccommodatemostoftheexistingdynamicinitialallocationmechanisms,includinggrandfatheringandauctions,aswellasnovelmechanisms,suchasrank-ordercontests.Weshowthatusing?rms’historicaloutputsforallocatingpermitsisneveroptimal,whileusing?rms’historicalemissionsisoptimalonlyinclosedtradingsystemsandonlyforanarrowclassofallocationmechanisms.Instead,itispossibletoachievesocialoptimalitybyallocatingpermitsbasedonanexternalfactorwhichisindependentofoutputandemissions.Weoutlinesuf?cientconditionsforasociallyoptimalrelativeperformancemechanismanddiscusstheissuesrelatedtothechoiceofasuitablemechanismforinitialallocation.

Duetothesepotentialbene?ts,weadvocateusingarelativeperformancemechanismwithanexternalfactorforthedynamicallocationofpermits.Thenumerousadvantagesofusingarelativeperformancemechanismincludeitsadaptabilitytochangingeconomic,technological,andotherconditions,aswellasapossibilityoftransferringriskofpossiblesystemicshocks(suchasoilpricechanges)totheregulator.Theadvantageofusinganexter-nalfactorinvolvesapossibilityofachievingsecondaryregulatorygoals,suchasrevenuemaximization,socialbettermentorreductioninotherenvironmentalproblems.Moreover,ifthesecondarygoalispoliticalagreeable,thepermittradingschememayalsoenjoygreaterpublicacceptance.

Allocatingpermitsforatargetpollutantbasedon?rms’relativeperformanceinexter-nalfactorincreases?rms’?exibilityinmeetingbothregulatorygoalsbychoosingthemostcost–effectiveapproach.Thatis,?rm’scost–effectivebehaviourmaydependonwhetherithascomparativeadvantageinabatementofthetargetpollutant,orintheproductionoftheexternalfactor.Wethinkthatsuchpotentialasymmetriesamong?rmsareimportantfortheoptimaldesignofpermitallocationschemes,atopicofpotentialfutureresearch.

Wealsoproposeanovelallocationmechanisminvolvingarank-ordercontest,whichisageneralizationofanall-payauction.Inanexternalfactorrank-ordercontest,?rmsarerankedintheorderoftheirrelativeproductionoftheexternalfactor,anditis?rm’srank,andnottheleveloftheexternalfactor,thatdetermines?rm’spermitallocation.Asthetheoretical

123

280IanA.Mackenzieetal.literaturesuggests,anallocationschemewithasuitablychosen“prize”structureisexpectedtoachievethesecondarygoalofmaximizingaggregateproductionoftheexternalfactor—thegoalwhichmaynotbeachievablewithotherallocationmechanisms.Inotherwords,byallo-catingtargetpollutantpermitsamong?rmsusingarank-ordercontestinsociallydesirableactivities(includingabatementofunregulatedgreenhousegasesorevencharitableactivities)aregulatorcan“killtwobirdswithonestone”byachievingemissioncontrolatthelowestsocialcostinoutputandpermitmarkets,andmaximizingaggregateamountofasociallybene?cialactivity.

Theexternalfactorrank-ordercontesthassomeadvantagesoverthepresentlyusedgrand-fatheringscheme.Whileregulatorsseemtoprefergrandfatheringduetoitspoliticalagree-abilityamongtheregulated?rms,theseschemescanbeunpopularwiththegeneralpublic.Incontrast,anexternalfactorcontestnotonlyhasapotentialofachievingsocialoptimality,butalsoitachievesasecondaryregulatorygoal(whichmaybeperceivedasachieving“fair-ness”),whilethegrandfatheringschemeinvolvinghistoricaloutputandemissionsachievesnoneofthesetwogoals.

WhilewehavepresentedargumentsinfavourofusingRPMsbasedonanexternalfactorinallocatingpermits,weneverthelessappreciatethepotentialpracticaldif?cultiesinvolv-inginthechoiceofasuitableexternalfactor.Thesuccessofthetradingschemerestsontheregulator’sabilityto?ndanexternalfactorthatisdesirable,politicallyagreeable,inde-pendentfromoutputandemissions,andallowsforanadequatecomparisonbetween?rms.Weneverthelesshopethattheargumentspresentedinthispapermaybeofrelevancetotheenvironmentalpolicymakers.

AcknowledgementsTheauthorswouldliketothankPaulAllanson,PaulHare,EdHopkins,MattiLiski,MiguelRodriguez,JayShogren,JoeSwierzbinski,participantsattheEuropeanAssociationofEnvironmen-talandResourceEconomists(EAERE)2005conferenceandtwoanonymousrefereesfortheirvaluablecommentsandsuggestions.TheEconomicandSocialResearchCouncil(ESRC)provided?nancialsupport(PTA-030-2004-00560).

References

BerglandH,ClarkDJ,PedersenPA(2002)Rentseekingandtheregulationofanaturalresource.MarResour

Econ16(3):219–233

BodeS(2005)EmissionstradingschemesinEurope:linkingtheEUemissionstradingschemewithnational

programs.In:HansjürgenB(ed).Emissionstradingforclimatepolicy:USandEuropeanperspectivesCambridgeUniversityPress,pp199–221

BodeS(2006)Multi-periodemissionstradingintheelectricitysector–winnersandloser.EnergyPolicy

34(6):680–691

B?hringerC,LangeA(2005)Onthedesignofoptimalgrandfatheringschemesforemissionallowances.Eur

EconRev49(8):2041–2055

CramtonP,KerrS(2002)Tradeablecarbonpermitauctions:howandwhytoauctionnotgrandfather.Energy

Policy30(4):333–345

CronshawMB,KruseJB(1996)Regulated?rmsinpollutionpermitmarketswithbanking.JRegulEcon

9(2):179–189

EllermanAD,WingIS(2003)Absoluteversusintensity-basedemissionscaps.ClimatePolicy3(S2):S7–S20FischerC(2001)Rebatingenvironmentalpolicyrevenues:output-basedallocationsandtradableperformance

standards.Resourcesforthefuture.DiscussionPaper01–22,WashingtonDC.

FischerC(2003)Combiningrate-basedandcap-and-tradeemissionspolicies.ClimatePolicy3(S2):S89–

S103

FranciosiR,IsaacM,PingryD,ReynoldsS(1993)AnexperimentalinvestigationoftheHahn–Nollrevenue

neutralauctionforemissionslicenses.JEnvironEconManage24(1):1–24

FranckxL,D’AmatoA,BroseI(2005)Multi-pollutantyardstickschemesasenvironmentalpolicytools..

14thannualmeetingoftheEuropeanAssociationofEnvironmentalandResourceEconomists(EA-ERE),Bremen,Germany

123

Theoptimalinitialallocationofpollutionpermits:arelativeperformanceapproach281FreixasX,GuesnerieR,TiroleJ(1985)PlanningunderincompleteinformationandtheRatcheteffect.Rev

EconStud52(2):173–191

GoulderLH,ParryI,BurtawD(1997)Revenue-raisingversusotherapproachestoenvironmentalprotection:

thecriticalsigni?canceofpreexistingtaxdistortions.RANDJEcon28(4):708–731

GovindasamyR,HerrigesJA,ShogrenJF(1994)Nonpointtournaments.In:TomasiT,DosiC(eds)Non-

point-sourcepollutionregulation:issuesandanalysis.KluwerAcademicPublishers,pp87–105

GreenJR,StokeyNL(1983)Acomparisonoftournamentsandcontracts.JPolitEcon91(3):349–364

GroenenbergH,BlokK(2002)Benchmark-basedemissionallocationinacap-andtradesystem.Climate

Policy2(1):105–109

HahnR,NollR(1982)Designingamarketfortradeableemissionspermits.InMagatWA(ed)Reformof

environmentalregulation.Ballinger,Cambridge,Massachusetts,pp119–146

HahnRW(1988)Promotingef?ciencyandequitythroughinstitutionaldesign.PolicySci21(1):41–66Holmstr?mB(1982)Moralhazardinteams.BellJEcon13(2):324–340

JensenJ,RasmussenTN(2000)AllocationofCO2emissionspermits:ageneralequilibriumanalysisofpolicy

instruments.JEnvironEconManage40(2):111–136

KlingC,RubinJ(1997)Bankablepermitsforthecontrolofenvironmentalpollution.JPublicEcon64(1):101–

115

KolstadCD(2005)ClimatechangepolicyviewedfromtheUSAandtheroleofintensitytargets.InHansjürgen

B(ed)Emissionstradingforclimatepolicy:USandEuropeanperspectives.CambridgeUniversityPress,pp96–113

KuikO,MulderM(2004)Emissionstradingandcompetitiveness:prosandconsofrelativeandabsolute

schemes.EnergyPolicy32(6):737–745

LazearEP,RosenS(1981)Rankordertournamentsasoptimumlaborcontracts.JPolitEcon89(5):841–864LeibyP,RubinJ(2001)Intertemporalpermittradingforthecontrolofgreenhousegasemissions.Environ

ResourEcon19(3):229–256

LyonRM(1982)Auctionsandalternativeproceduresforallocatingpollutionrights.LandEcon58(1):16–32LyonRM(1986)Equilibriumpropertiesofauctionsandalternativeproceduresforallocationtransferable

permits.JEnvironEconManage13(2):129–152

MaluegDA,YatesAJ(2006)Citizenparticipationinpollutionpermitmarkets.JEnvironEconManage

51(2):205–217

MellersBA(1982)Equityjudgment:arevisionofAristotelianviews.JExpPsycholGeneral111:242–270MellersBA(1986)“Fair”allocationsofsalariesandtaxes.JExpPsychol:HumanPerceptionPerformance

12:80–91

MillimanSR,PrinceR(1989)Firmincentivestopromotetechnologicalchangeinpollutioncontrol.JEnviron

EconManag17(3):247–265

MoldovanuB,SelaA(2001)Theoptimalallocationofprizesincontests.AmEconRev91(3):542–558MoldovanuB,SelaA(2006)Contestarchitecture.JEconTheory126(1):70–96

MookherjeeD(1984)Optimalincentiveschemeswithmanyagents.RevEconStud51(3):433–446NalebuffBJ,StiglitzJE(1983a)Information,competitionandmarkets.AmEconRev73(2):278–283

NalebuffBJ,StiglitzJE(1983b)Prizesandincentives:towardsageneraltheoryofcompensationandcompe-

tition.BellJEcon14(1):21–43

NewellRG,PizerW(2006)Indexedregulation.DiscussionPaper06–32,ResourcesfortheFuture,Washington

DC.

OehmkeJ(1987)Theallocationofpollutantdischargepermitsbycompetitiveauction.ResourEnergy

9(2):153–162

ParryIWH(1995)Pollutiontaxesandrevenuerecycling.JEnvironEconManage29(3):S-64–S-77

ParryIWH(1997)Environmentaltaxesandquotasinthepresenceofdistortingtaxesinfactormarkets.Resour

EnergyEcon19(3):203–220

ParryI,WilliamsRC,GoulderL(1999)Whencancarbonabatementpoliciesincreasewelfare?Thefunda-

mentalroleofdistortedfactormarkets.JEnvironEconManage37(1):52–84

PizerW(2005)Thecaseforintensitytargets.DiscussionPaper05-02,ResourcesfortheFuture,Washington

DC.

RequateT,UnoldW(2003)Environmentalpolicyincentivestoadoptadvancedabatementtechnology:will

thetruerankingpleasestandup?.EurEconRev47(1):125–146

RubinJ(1996)Amodelofintertemporalemissiontrading,bankingandborrowing.JEnvironEconManage

31(3):269–286

SkaperdasS(1996)ContestSuccessFunctions.EconTheory7(2):283–290

SchennachSM(2000)TheeconomicsofpollutionpermitbankinginthecontextofTitleIVofthe1990Clean

AirActAmendments.JEnvironEconManage40(3):189–210

123

282IanA.Mackenzieetal.SchmalenseeR,JoskowPR,EllermanAD,MonteroJ-P,BaileyEM(1998)Aninterimevaluationofsulphur

dioxideemissionstrading.JEconPerspect12(3):53–68

ShleiferA(1985)Atheoryofyardstickcompetition.RANDJEcon16(3):319–327

StavinsRN(1998)Whatcanwelearnfromthegrandpolicyexperiment?LessonsfromSO2allowancetrading.

JEconPerspect12(3):69–88

TietenbergT(1985)Emissionstrading:anexerciseinreformingpollutionpolicy.ResourcesfortheFuture,

Washington,DC

VanDykeB(1991)Emissionstradingtoreduceaciddeposition.YaleLawJ100:2707–2726

WeitzmanM(1980)The‘Ratchetprinciple’andperformanceincentives.BellJEcon11(1):302–308

YatesAJ,CronshawMB(2001)Pollutionpermitmarketswithintertemporaltradingandasymmetricinfor-

mation.JEnvironEconManage42(1):104–118

123

-

初始排污权核算技术报告

XXXXXXXX有限责任公司初始排污权核算技术报告编制单位XXXXXXXX有限责任公司20xx年10月16日初始排污权核算技术报告…

-

初始排污权核算技术报告

XXXXXXXX有限责任公司初始排污权核算技术报告编制单位XXXXXXXX有限责任公司20xx年10月16日初始排污权核算技术报告…

-

河北省初始排污权核算技术报告

唐山天联水泥制品有限责任公司初始排污权核算技术报告1单位概况11单位基本信息唐山天联水泥制品有限责任公司前身为丰润县水利局水泥管厂…

-

排污权核算技术报告 (报送)

初始排污权核算技术报告20xx年11月4日目录1排污单位概况11排污单位基本信息12基本情况及项目组成13物耗能耗2工艺流程和产污…

-

排污许可技术报告编制大纲

河北省排污许可技术报告编制大纲河北省环境保护厅制二一五年目录1总论111前言112编制依据12排污单位现状221地理位置及周边关系…

-

排污许可证请示报告

关于填报排污许可证申请表的请示报告公司领导根据我国制定的环境管理八项制度之一的排污许可证制度的精神及上级有关环保部门的要求从今年起…